Pittsburgh is less a city than it is a collection of small communities divided along arbitrary lines. Drive a few miles on Penn Avenue from Downtown to the outer edges of the East End, and you’ll pass through at least five of them, likely without realizing it.

In the East End of Pittsburgh, inside an eruv, a ritual enclosure installed by some Orthodox Jewish communities to allow for freer movement during the Sabbath, is a neighborhood of roving green lawns and 19th century architecture. Squirrel Hill is one of the more beautiful areas of the city, its quiet streets lined with beech trees and spacious family homes built long before its current residents were born. It’s an affluent neighborhood, with median home prices hovering around $600,000—considerable for Pittsburgh. The tight-knit community was once even home to Fred Rogers, the greatest neighbor who has ever lived.

Videos by VICE

Despite its serene atmosphere, Squirrel Hill gave birth to some of the most groundbreaking rap music that came out of the city in the aughts. Along with its adjacent offshoot of Point Breeze, it was the childhood neighborhood of Malcolm McCormick, better known as Mac Miller. Miller attended the neighborhood’s high school, Taylor Allderdice. Before Mac, the high school also set the stage for Wiz Khalifa and the beginnings of Taylor Gang, his record label and entertainment business.

“Wiz opened the door for everyone,” Quentin Chandler Cuff said. “All of Taylor Gang.” Quentin, who goes by Q, is a friend and former business partner of the late Miller. He now tour-manages EarthGang, a hip-hop duo from Atlanta. “Looking up to those guys I think inspired a lot of not only artists but managers, producers, engineers, etc.”

Three miles from Squirrel Hill, also in the East End, is a neighborhood called The Hill District, which was dominated by Black-owned businesses until the 1950s, when local governments decided that it was in dire need of economic redevelopment. Buildings were razed, 8,000 residents (the majority of whom were Black) were displaced, and the Civic Arena, home to the Pittsburgh Penguins for 43 years, was built in their place. The neighborhood never recovered, losing over 70 percent of its residents during the subsequent decades. Today, abandoned houses and storefronts sit between overgrown patches of land. Nearly half the remaining residents live below the poverty line, according to US Census Data.

This was the childhood neighborhood of Travon Smart, better known as Jimmy Wopo, a rising trap music star whose hit song “Elm Street” has been streamed over 8 million times on Spotify.

Mac left Pittsburgh when his music career took off, opting for the sunnier weather of Los Angeles over the dreary Pittsburgh skies (the city sees only about 160 sunny days per year, though, as a resident, this number feels shockingly high). Smart opted to stay in Pittsburgh as his music began to explode, enjoying the fame that came with being a local legend.

In 2018, within three months of one other, both were dead. Smart—who wanted to use his rap career to leave gang life behind—was shot to death in a drive-by shooting In the Hill District. Mac—who had fled Los Angeles for New York partly to get away from the culture that had aided his slide into substance abuse—passed from an overdose shortly after returning to LA.

At the start of the year, Pittsburgh had claim to one of the most revered and respected artists in the world of hip-hop, as well as one of its brightest rising stars. Before the leaves had turned, the city had lost Mac and Wopo. Pittsburgh’s budding hip-hop community was left wounded and wondering how, if at all, it could recover.

“If last year hadn’t happened, we’d probably be having a whole different conversation,’ said Ian Benjamin Welch, who raps under the name Benji. Like many of the young hip-hop artists Noisey spoke to for this story, he feels as though Pittsburgh’s momentum as a rap incubator has stalled, that the spirit of solidarity that once defined it has all but disappeared. “If we hadn’t lost Mac and Wopo, you might be talking to like 20 of us all together right now.”

Welch isn’t especially tall, but he stands out, with a squat, athletic build from his days as a long jumper and triple jumper at Duquesne University and flowing dreadlocks that frame a round jaw and radiant smile. He has a show tonight at Cattivo, a Lawrenceville staple that has been home to artists from marginalized communities for over 20 years, including hosting some of the best drag shows in the city.

Ian started rapping a couple of years ago, under the name Sir Courtesy, then switched up his style and became Benji. in 2018. Smile, You’re Alive!, his record from last year, helped Benji. distinguish himself within a crowded field of rappers in the city. In addition to write-ups in local media like City Paper and WYEP, he’s one of the few rappers here who can command a crowd on his own, without having to be part of a larger billing.

Before the tragic loss of Wopo and Mac, Benji. said, the scene was unified and coming into its own. Artists were collaborating and supporting each other, no longer burdened by the pressure of being “next up,” since there were already titans putting on for Pittsburgh. The last year has changed things.

Once the hierarchy of the scene was disrupted, Benji. said—Mac Miller and Wiz Khalifa at the top, with Wopo clearly the next to break big—the direction for the city was lost. It’s a fairly simple matter of marketing: With more Pittsburgh rappers making names, the scene would attract more attention, along with that attention came increased opportunities for local artists, including introductions within the industry, opening slots on tour, and features on songs. Benji. himself had been invited to open for Mac Miller on the Pittsburgh stop of his tour, an opportunity that did not come to fruition due to Miller’s untimely death.

As a result, Benji. said, multiple rappers are vying to be the next torchbearer for the city, operating under the belief that there are a limited number of spots.

“It’s competitive now,” he said. “Everyone’s been watching this whole time. And, like, everyone knew that but didn’t really speak on it.” In Benji’s eyes, Mac’s continual stardom and Wopo’s breakthrough represented a new chapter for the city, where the talent would finally be recognized as Pittsburgh became a more prominent hub for exciting rap music. Now, he said, the talent is still here, but it’s aimless.

Benji. hails from Homewood originally, a neighborhood that, despite being on the opposite side of town, has a close and historical kinship with Wopo’s Hill District. When the city razed housing in the Hill for the Civic Arena, many of the predominantly Black families that were displaced moved to Homewood, a shift that, along with increased white flight from the neighborhood, caused an increase in the Black population from 22 percent in 1950 to over 60 percent by 1960. In the aftermath of the 1968 Pittsburgh riots, the housing and businesses in the neighborhood were ravaged. Now, roughly 25 percent of residents in the neighborhood live below the poverty line, and Homewood South has the highest homicide rate in Allegheny County.

Benji., for his part, said he largely avoided gang life by staying active in athletics and his church. “We had our little secluded area,” he said about the block he grew up on. “Me and my brother, we weren’t really out in the neighborhood.”

Benji.’s rap is freewheeling and sunny, even while tackling heavy subject matter. But Smile, You’re Alive! captures Benji. at his lowest point. Three days before his best friend committed suicide, a paternity test revealed that the child he was expecting with his girlfriend wasn’t his. A mission statement of sorts for the album, opener “Rain Down” sees him processing his heartbreak, devastation, and continued search for the beauty of existence through upbeat, poppy instrumentals and a voice that at times oscillates between pitches within the same syllable. “It’s okay to be nervous,” he raps. “It’s ok to feel worthless / cause then there’s people like us around who remind you you’re worth it.”

This mentality is rare in Pittsburgh rap, where most of the music is bleak—albeit presented with the signature gallows humor of a depleted Rust Belt city. Wopo provided myriad examples of this in his work, like when he subverted childhood cartoon characters in rhymes about murder on his signature hit, “Elm Street”: “On my Pokemon shit / I let it peak-at-you.” PK Delay, a younger rapper hoping to carry a torch for the local trap scene that Wopo helped put on the map, contrasts a flow that is dreamy and distant with the staccato of 808s and gritty lyrics. On “Cold Heart,” a track from 2018’s Pretty the Pico, he raps “You might be my son, I ain’t doubting you / You might be my son, I ain’t proud of you.”

Even outside of the trap scene, poppier artists like Mars Jackson are no stranger to this feeling of anxiety. His 2018 Misra Records release, Good Days Never Last Forever, Mars displays a coolness and confidence, but the title, opener, and outro convey a clear sense of dread: ambient synth opens the album, and Mars bitterly quips 4 times in a row that “I know this shit don’t last forever / but I want this shit forever.” It was released months before the deaths of Wopo and Mac, yet the despair feels prescient.

Benji.’s optimism is a byproduct of his life experience: He’s still here. When he’d reached bottom in his personal life after the paternity news and his friend’s death, he said he found himself on the 10th Street Bridge in Pittsburgh’s South Side neighborhood, contemplating an end to his pain.

“I could be dead,” he said. “I could’ve jumped off that fucking bridge; we wouldn’t be having this conversation today. Knowing that didn’t happen, it’s like, Yo, I went up against myself and I won.”

Now, he gets to thrive and pass his energy on to others. More importantly, he said, he gets to do it with his best friends, including Jourdn Martin, AKA SlimthaDJ, his roommate and primary producer. He’s set to release a new album, WATERCUP, in September via Misra Records.

“We saw the worst of it here,” he said. “You see what happened to Wopo. You lose friends here, especially being Black.”

Despite its blue collar reputation, Pittsburgh has always been a classist city—a fact evident in the layout of its neighborhoods. In Lawrenceville during the steel heyday of the early 20th century, the houses that sit up on the hills between Butler Street and Penn Avenue were for management at the mills, while the working class families were stuck in the flat portions at the bottom of the hill, where, according to local lore, the muck and shit would flow during rainstorms. Ironically, these larger multi-family units at the bottom of the hill, with their complicated floor plans and layouts, are considerably more expensive in the modern real estate market, as they’re renovated into massive open concept houses for Pittsburgh’s tech worker nouveau riche.

But that stratified mindset still exists today, with Black families primarily residing in the small handful of neighborhoods where they feel welcome. Pittsburgh rappers continue to grapple with the city’s legacy of regressive racial politics and segregated neighborhoods. The city’s police force is primarily white even in predominantly Black neighborhoods, and has recently committed several high profile shootings against Black citizens of the city, including 17-year-old Antwon Rose this past summer—a shooting that the city failed to properly prosecute.

“Wopo and [Pittsburgh rapper and frequent Wopo collaborator] Hardo had a show [opening for Mac Miller] that had to get relocated at the last minute because the venue and Pittsburgh Police were afraid of violence,” Benji. said. “Just based off of lyrics. They didn’t understand that it’s just music. It’s what they’re seeing on a daily basis; it doesn’t mean they’re doing it.”

“That was supposed to be a moment,” Quentin said about the potential Wopo and Mac show that Benji. described. “If the venues block artists from creating moments, how do you build a scene?”

Both artists describe a frustrating arts environment for Black performers, one where they have to convince a predominantly white music industry—the people and institutions that fund grants and control access to venues in the city—that what they are doing is art, and therefore has merit, before they are even allowed to share that art with their community.

Much of this difficulty can be tied back to one critical event in Pittsburgh rap: the closing of Shadow Lounge. Shadow Lounge was a Pittsburgh rap institution for more than 10 years in the East Liberty neighborhood, where like-minded artists and fans could gather to see Wiz, Mac, and the best of what Pittsburgh rap had to offer. It closed in 2013, after ownership got tired of dealing with the headaches of liquor license ownership and the development and gentrification of its surrounding neighborhood.

“That’s what Pittsburgh needs again,” said Jeremy Kulousek, aka Big Jerm, a producer who is largely responsible for shaping the sound of Pittsburgh rap, including the bulk of Wiz Khalifa and Mac Miller’s early recordings. “That was one thing that [Mac] had talked about. I don’t know how realistic it was, but he had talked to Justin, who ran Shadow Lounge, about starting something else up or buying that space back.”

“It’s hella fucked up,” Anthony Willis said. Willis, who raps under the name My Favorite Color, hails from Penn Hills, a few miles northeast of Homewood and the second largest township in Allegheny County next to the City of Pittsburgh. “Being an artist, you just notice that you have to deal with a lot of fucked-up ass shit just to get your message out. I compare it to a line by Isaiah Rashad, where he said, ‘How you tell the truth to a crowd of white people?’ But like, that guy made it into that building to tell the truth to a crowd of white people. There was a time at that venue where Black people probably weren’t even allowed to come. So you just gotta make your way in there and tell your truth.”

Penn Hills is known as a football powerhouse, the childhood neighborhood of NFL players like Aaron Donald and Barry Church. Despite the fact that Penn Hills is 34 percent Black, the suburb is often an afterthought for those in the city, particularly Black residents in the scene. They have yards in Penn Hills, whereas Homewood, Hill District, and East Liberty residents predominantly see cracked pavement and vacant lots.

“I never felt overlooked per se, because I was and still am cooler than a lot of those [people],” Willis said. “But there were definitely times where I’d be hanging with city kids, and they’d joke around when I did certain things, like, ‘That’s some Penn Hills shit’—or if I did something cool, they’d be like, ‘You sure he’s from Penn Hills?’”

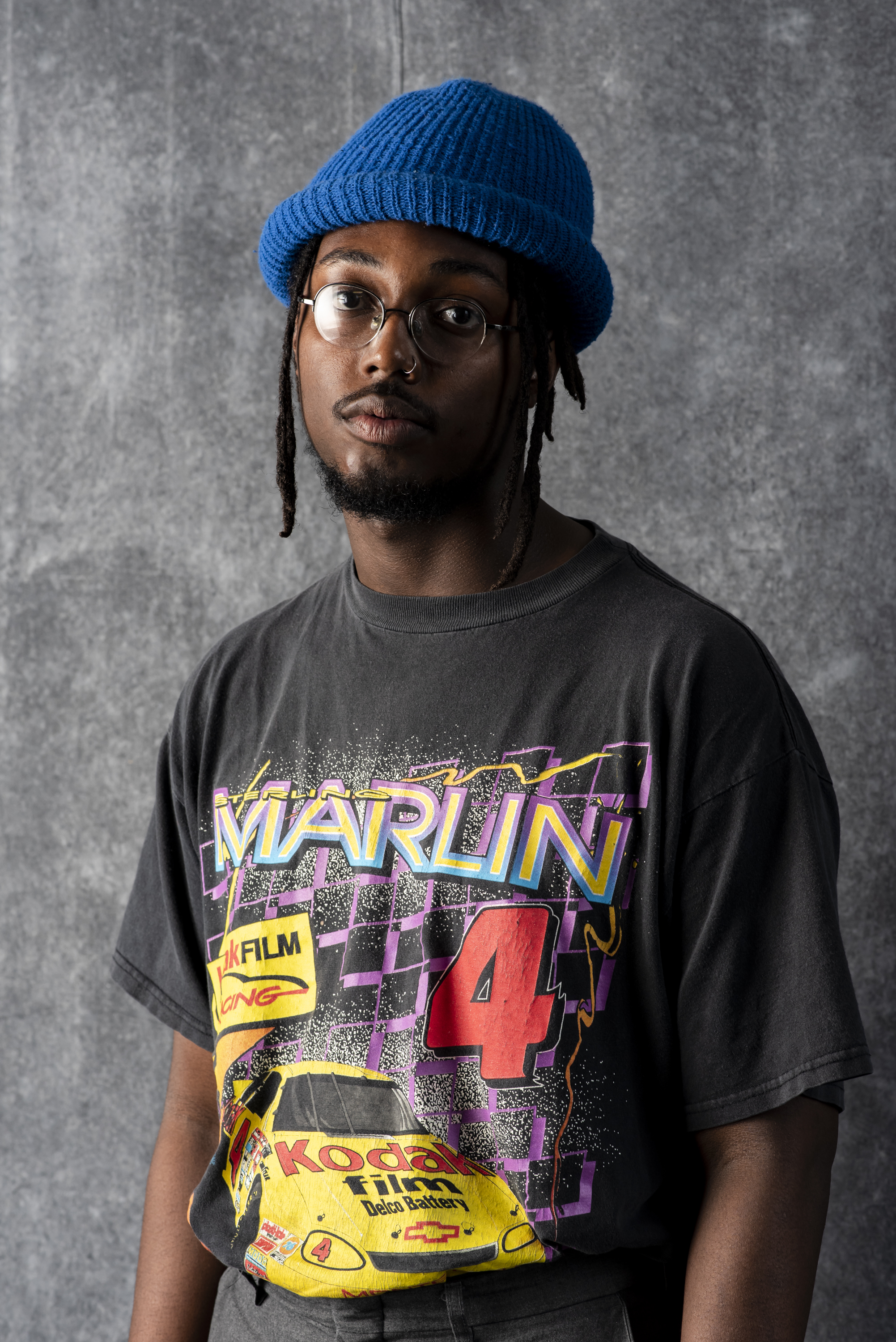

Willis—he refuses to go by Anthony and bristles if he hears his given first name—has a unique aesthetic. Dreadlocked, with wiry glasses that slip down his nose, he can usually be seen in an assortment of baggy vintage Polo denim or NASCAR shirts from his trips to thrift shops around the city. His inexpensive apparel is usually highlighted by Raf Simons x Adidas sneakers or coveted Jordan 1 colorways, signaling that this is a curated fashion statement and not the happenstance of someone dressing like a slouch.

His music is powerful. Each bar drips with the confusion and existential dread of a man who feels out of place in his world. “I jump the broom / married to flowers that bloom / Cancun honeymoon / suicide in the room / Home sweet home in the hotel like oh well / got me asking questions to a magic conch seashell / Check the mailbox and all I ever get’s blackmail” he raps on “Still,” an unreleased track from his latest project, Velma.

Some of this feeling of displacement is a result of being a transplant: Willis moved to Pittsburgh in his teenage years after spending the bulk of his life in the Inglewood area of Los Angeles. “It’s mostly the weather,” he said. “Seasonal depression is real. Like, out here, [people] be getting sad during the winter. Out in LA, it’s nice every day, so if you’re depressed, you’re just depressed for real.”

Willis sees the competition in the city’s rap scene, and he’s resentful of it.

“I just wish more artists would work together,” he said. “We see each other and talk to each other, but nobody is reaching out to work on tracks together or support each other’s music, really.”

His next project is due out in the coming months. It’s a truly cohesive piece of art, tracking Willis’ anxieties about making it and the compromises he fears he will have to make if he wants to get the recognition and money he feels he deserves. On “Funeral,” the album’s closing track, Willis imagines the reaction to his death and the attendees viewing him in his casket.

Home to over 600,000 people at its peak, Pittsburgh lost nearly 50 percent of its population between 1970 and 1990. The city’s economy has largely bounced back, partly thanks to the growth of America’s technology, education, and healthcare industries. However, for musicians and artists in the rap scene, the opportunities for growth are still outside of the city limits.

Benji. is unsure when he’ll leave, but said it’s a question of when and not if. “There still isn’t enough infrastructure here for it to be a sustainable thing,” he said. “But I think you’ll see a large return for those that do go.” Still, he said “I wouldn’t mind this being my base here”—once he’s found success, that is.

Even for a small market, Pittsburgh rappers have significantly fewer opportunities than in comparably sized cities. Detroit and, in particular, Atlanta, are similarly-sized cities that have held onto their hip-hop artists as they branch out onto a national stage—likely because local artists are able to take advantage of local labels and venues, as well as a larger audience of rap fans.

In a 2018 interview with GQ, Wiz Khalifa described how “This Plane,” a song from his album Deal or No Deal, was inspired in part by the relatively lukewarm reception to his music back home, just as it was gaining steam outside the city. “I was doing a lot of things at that time that weren’t in Pittsburgh,” Khalifa said. “It was weird, because I was getting a lot more love outside of Pittsburgh than I was in Pittsburgh,” he said. “[That song] was kinda like, ‘Y’all better fuck with me now because y’all gonna miss me when I’m gone, because I knew I was up outta here.’”

Willis, for his part, already has his plans lined up: he’s headed to Los Angeles this August.

The move is a homecoming of sorts, given Willis’ childhood in Inglewood. The opportunities are vast, as long as he can avoid the trappings of gang life that his move to Pittsburgh helped mitigate. Much of his extended family is affiliated, and he describes a run-in he had in Compton when he was visiting with his girlfriend, model Tamia Blue.

“They came up and hassled me,” he said. “I just told them who my brother was, and once they figured out I wasn’t lying, they let me be…I’m not super worried about it. I know how to move down there, how to sense bad situations, or if there’s someone who is wildin’ that I shouldn’t stay around. I’ll be okay.”

Both Benji. and Willis said they can envision a day when leaving the city to find a wider audience will no longer be necessary. Part of that will come when another venue fills the void left by Shadow Lounge, while the other will come down to changing attitudes in the industry over time, as gatekeepers become more diverse and accepting of rap. Willis thinks it’s at least five years out, while Benji. thinks that it could happen in the next year or two, if the right artist props the scene up.

The bridge where Benji. almost ended his life overlooks the Monongahela River. At night, the formerly desolate downtown area of Pittsburgh is lit in the dull orange of street lights and corporate logos, as well as the luxury condo complexes and upscale dining establishments that have become synonymous with the rejuvenation of the city’s Cultural district—but only for those who can afford it.

As the city moves further away from its industrial past, the river’s water gets less polluted each year, signaled by the increase in mayflies that swarm joggers on the riverside trails. Despite the improvement, locals still know not to eat the fish that can be caught from the rivers’ shores. Deep beneath its murky green water, there are hundreds of thousands of pieces of scrap steel, discarded from the mills and plants that dotted the shores a century prior, when the city’s economy, though far from perfect, still had the infrastructure to provide a viable home for its residents. The jagged edges along the sides that were hand-cut look like crude pieces to a puzzle, its solution forgotten with the generations that have died.

Casey Taylor is a writer based in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter.

Tyler Calpin is a photographer based in Pittsburgh. You can find more of his work on Instagram.

More

From VICE

-

Perry Farrell performs with Jane's Addiction on September 11, 2024. Photo by Erik Pendzich/Shutterstock. -

Photo by Angga Budhiyanto/ZUMA Press Wire/Shutterstock -

Kendrick Lamar announces his Super Bowl LIX halftime show via YouTube. -

Rich Homie Quan in 2017. Photo by Larry Marano/Shutterstock.