On Tuesday, the Edmonton Police Service (EPS) shared a computer generated image of a suspect they created with DNA phenotyping, which it used for the first time in hopes of identifying a suspect from a 2019 sexual assault case. Using DNA evidence from the case, a company called Parabon NanoLabs created the image of a young Black man. The composite image did not factor in the suspect’s age, BMI, or environmental factors, such as facial hair, tattoos, and scars. The EPS then released this image to the public, both on its website and on social media platforms including its Twitter, claiming it to be “a last resort after all investigative avenues have been exhausted.”

The EPS’s decision to produce and share this image is extremely harmful, according to privacy experts, raising questions about the racial biases in DNA phenotyping for forensic investigations and the privacy violations of DNA databases that investigators are able to search through.

Videos by VICE

In response to the EPS’s tweet of the image, many privacy and criminal justice experts replied with indignation at the irresponsibility of the police department. Callie Schroeder, the Global Privacy Counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, retweeted the tweet, questioning the usefulness of the image: “Even if it is a new piece of information, what are you going to do with this? Question every approximately 5’4″ black man you see? …that is not a suggestion, absolutely do not do that.”

“Broad dissemination of what is essentially a computer-generated guess can lead to mass surveillance of any Black man approximately 5’4″, both by their community and by law enforcement,” Schroeder told Motherboard. “This pool of suspects is far too broad to justify increases in surveillance or suspicion that could apply to thousands of innocent people.”

The victim of the case only had a limited description of the suspect, “describing him as 5’4”, with a black toque, pants and sweater or hoodie” and “as having an accent,” making for a vague, indistinguishable profile.

“Releasing one of these Parabon images to the public like the Edmonton Police did recently, is dangerous and irresponsible, especially when that image implicates a Black person and an immigrant,” Jennifer Lynch, the Surveillance Litigation Director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation told Motherboard. “People of color are already disproportionately targeted for criminal investigations, and this will not only exacerbate that problem, it could result in public vigilantism and real harm to misidentified individuals.”

The criminal justice and policing system is laden with racial biases. A Black person is five times more likely to be stopped by police without cause than a white person, and Black, Latinx, and people of color are more likely to be stopped, searched, and suspected of a crime even when no crime has occurred.

Seeing the composite image with no context or knowledge of DNA phenotyping, can mislead people into believing that the suspect looks exactly like the DNA profile. “Many members of the public that see this generated image will be unaware that it’s a digital approximation, that age, weight, hairstyle, and face shape may be very different, and that accuracy of skin/hair/eye color is approximate,” Schroeder said.

In response to the criticism after the release of the image and the use of DNA phenotyping, the Edmonton Police Department shared a press release Thursday morning, in which it announced it removed the composite image from its website and social media.

“While the tension I felt over this was very real, I prioritized the investigation – which in this case involved the pursuit of justice for the victim, herself a member of a racialized community, over the potential harm to the Black community. This was not an acceptable trade-off and I apologize for this,” wrote Enyinnah Okere, the chief operating officer of EPS.

Parabon NanoLabs sent Motherboard a number of case studies where DNA phenotyping alone helped solve murder and assault cases. However, the case studies do not address the larger concerns, which are a lot harder to measure—such as how many innocent people were questioned before the final suspect was arrested, and how the suspect image may have affected the public’s racial biases.

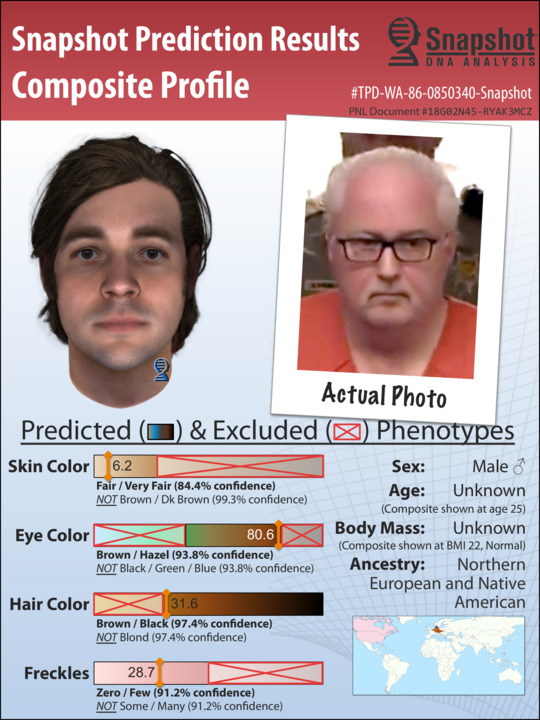

According to Parabon, it has worked on hundreds of law enforcement investigations. On its site are a number of case studies, with many showing the comparison between the DNA profile and actual photo of the suspect. There are some similarities between the two photos, in that they both reflect the same race, gender, eye and hair color. Often, however, the resemblance between the generated image and the suspect ends there.

“We’re making predictions just from the DNA, so we have only so much information. And so when we make those predictions, it’s a description and these are standing in. If the police had a witness, then they wouldn’t need us,” Dr. Ellen Greytak, the director of bioinformatics and technical lead for the Snapshot division at Parabon NanoLabs, told Motherboard. “We’re providing facts, like a genetic witness, providing this information that the detectives can’t get otherwise.”

“It’s just the same as if the police had gotten a description from someone who, maybe you know, didn’t see them up close enough to see if they had tattoos or scars, but described the person. What we find is that this can be extremely useful especially for narrowing down who it could be and eliminating people who really don’t match that prediction,” Greytak said. “In these cases, by definition, they always have DNA and so we don’t have to worry about the wrong person being picked up because they would always just match the DNA.”

According to Greytak, the technology creates the composite image by running the suspect’s DNA through machine learning models that are built on thousands of people’s DNAs and their corresponding appearances.

“The data that we have on the people with known appearances are from a variety of sources, some of them are publicly available, you can request access for them. Some of them are from studies that we’ve run, where we’ve collected that information,” Greytak said.

The DNA dataset being used to create these composites raises more red flags regarding the privacy questions of DNA profiling. The “variety of sources,” include GEDmatch and FamilyTree DNA, which are open-source, free genealogy websites that give you access to millions of DNA profiles.

“People should know that if they send their DNA to a consumer-facing company, their genetic information may fall into the hands of law enforcement to be used in criminal investigations against them or their genetic relatives. None of this data is covered by federal health privacy rules in the United States,” Lynch said. “While 23 and Me and Ancestry generally require warrants and limit the disclosure of their users’ data to law enforcement, other consumer genetic genealogy companies like GEDmatch and FamilyTree DNA provide near-wholesale law enforcement access to their databases.”

Parabon NanoLabs claims that the images they generate aren’t based on race, but on their genetic ancestry. “When we talk about a person’s genetic ancestry, or biogeographic ancestry, [which] is the term that we use for that, that is a continuous measure versus race, which is categorical,” Greytak said.

However, researchers argue that taking familial origin into consideration while DNA profiling, as Parabon NanoLabs does, is not an objective measurement because it results in general populations being seen as more criminal than others.

“Whereas the conventional use of DNA profiling was primarily aimed at the individual suspect, more recently a shift of interest in forensic genetics has taken place, in which the population and the family to whom an unknown suspect allegedly belongs, has moved center stage,” researchers led by anthropologist Amade M’charek wrote in a study titled “The Trouble With Race in Forensic Identification.” “Making inferences about the phenotype or the family relations of this unknown suspect produces suspect populations and families.”

After a 2019 Buzzfeed investigation revealed that GEDmatch allowed police to upload a DNA profile to investigate an aggravated assault, the site changed its policies so that users had to opt in to law enforcement searches. Still, investigators are able to use a number of similar databases to upload suspect’s DNA and map out the suspect’s family tree until they can pinpoint the suspect’s true identity.

A notorious case in which this tactic proved successful was in finding the Golden State Killer, a serial killer named Joseph James DeAngelo. After uploading his DNA to GEDmatch, investigators were able to find one of his family members who was already in the system, and trace DeAngelo down decades after he committed the crime.

Many police departments have been collecting DNA from innocent people and people who commit minor crimes, such as Orange County, which has a database of more than 182,000 DNA profiles, almost all from people who faced misdemeanor charges, which include petty theft or driving with a suspended license. Several attorneys filed a lawsuit against the county, who claim that the database is against California law. The lawsuit says that handing over DNA is a “coercive bargain,” because those who hand over a DNA sample will receive lighter punishments or even a dismissed case.

A similar lawsuit was filed in New York City by the Legal Aid Society, which accuses the city of operating a DNA database that violates state law and constitutional protections against unreasonable searches. These DNA databases again perpetuate the pervasive racial biases of the criminal justice system. Because people of color, especially Black and Latino people, make up 75 percent of people arrested in the past decade in NYC, the DNA database further inscribes criminality onto marginalized demographics.

While race isn’t necessarily measured by DNA phenotyping, race is produced semiotically by the visual nature of DNA composite profiles and in the already biased DNA datasets, which these profiles are derived from. The usage of DNA phenotyping may have broken open a few cold cases, but we have to ask: at what cost.

This article is part of State of Surveillance, made possible with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures. The series will explore the development, deployment, and effects of surveillance and its intersection with race and civil rights.