There’s not much to do in Morton, Mississippi, population 3,630. There’s a city park with playground equipment and sports fields, deserted in the Saturday morning heat. There’s a state park pool, populated by local white teenagers and tourists from nearby counties. There are about five Hispanic markets, a few Mexican restaurants, a handful of other restaurants, a downtown strip, and a pharmacy that doubles as an ice cream shop.

And there are chicken plants. The biggest employer in town is Koch Foods. Koch operates a slaughter plant (which makes downtown smell like a dumpster), as well as a packing facility (which has a more pleasant McNuggets-esque odor), an outlet store, a hatchery, a feed mill, and in neighboring Forest, a deboning plant.

Videos by VICE

Morton’s poultry industry became infamous on August 7, when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents raided seven chicken plants in six Mississippi cities, arresting 680 workers. These arrests included 300 workers in Morton’s Koch facilities and a smaller chicken plant called PH Food. It was the first day of school, and many students were left waiting for parents who never picked them up. Terrified children were taken to a fitness center in Forest, where they spent the night in the care of volunteers. The next day, 153 out of about 500 Latinx students enrolled in Morton public schools were absent.

More than a month after the raids, some Morton parents have not returned. Kids are still being cared for by friends and relatives. According to locals, in the two days following the raid, PH Food fired another roughly 100 Latinx employees—almost its entire remaining workforce—likely because they were undocumented. This religiously devout town, where only 7 percent of adults hold college degrees, is reeling from the raids. Revenue is down for local businesses. The lines on the chicken plants are staffed by primarily Black workers, now that the Hispanic employees are gone. Nearly everyone has opinions about both the chicken plants and the undocumented workers.

Some white residents are appalled by the raids. “The people making these decisions, may it weigh down upon their heart,” said Patrick Kelly, 51, who owns the town’s only supermarket and single hardware store. “And those ICE agents, when they see them people crying, how do they stand it?”

Recently, a longtime customer came in with her little boy and asked Kelly to cash her husband’s check. Her husband is in Natchez, Mississippi, two hours south, where in July, a vacated 2,232-bed prison became the state’s second immigration detention center. Kelly cashed the check, stepped into the front office, and cried.

A boisterous, wiry white man with a thick Southern twang, Kelly has lived alongside Hispanic people his whole life. He’s known Daniela Vargas—the 24-year-old “DREAMer” from Morton, who made national headlines for being plucked by ICE directly after speaking at an immigration press conference—since she was a child.

Following the raids, Kelly has called congressional and state representatives and written character witness statements and proof of residency letters for his neighbors, including the woman with the little boy. He has also appeared in federal court as a character witness.

Kelly had a recent phone conversation with Republican Congressman Michael Guest, who represents Morton. “Why don’t they give them some temporary work visa? Somebody can do something!” Kelly recalled saying.

Guest told him, “They try to have meetings and the Democrats won’t show up, and then on the other hand… Trump won’t show up or he’ll walk out.” Through a spokesperson, Guest confirmed that he had talked to Kelly but would not discuss that conversation or the raids. He has consistently supported Donald’s Trump’s immigration policy—including voting against a path to citizenship for DREAMers and supporting shutting down the government in an attempt to fund the border wall.

The division of labor in Morton’s chicken industry has been racialized ever since B.C. Rogers opened the first poultry business here in 1932. What began as a hen-and-egg operation grew grew to include a slaughter plant in 1949. According to Angela Stuesse, author of Scratching Out a Living: Latinos, Work and Race in the Deep South, prior to World War II the plants were likely staffed by white men. More white women began to work the lines during the war, but the B.C. Rogers plant remained almost entirely white through the 70s, with Klan in management positions. B.C.’s daughter, Martha Rogers, said she can’t remember when the plant integrated. She thinks maybe it was around 1972, the year her father died. She doesn’t recall any pushback due to integration.

Helen Stuart, 73, worked at the Morton plants nearly continuously from 1963 until 2009. She was a line supervisor when the Rogers family sold to Koch in 2001. A white teen when she began, Stuart remembers her supervisors as being all white men until the 1980s, when some white women were promoted to management. She can’t recall any supervisors of color prior to the early 90s.

In the 1970s, Black poultry workers first attempted to organize the local non-union plants. New white hires were willing to cross picket lines. Stuart remembers one strike in particular, in the early 80s. “The Blacks walked out of there,” she said. But this time, they were joined by some white employees. Rogers knew about the strike the night before it happened, because a white coworker had asked her to join. Instead, she reported it to management, and eventually the employees returned to work without unionizing.

The man largely responsible for first bringing Latnix people to Morton was Tito Echiburu, a tennis star who left his native Chile to study accounting after being recruited to the Mississippi State University tennis team. At the time, the university was all-white. Echiburu became a tennis coach and close friend of B.C.’s son, John Rogers, and moved to Morton in 1973 to become CFO of B.C. Rogers Poultry. According to Echiburu, his was the first Hispanic family in town.

By the early 90s, B.C. Rogers had added new plants but didn’t have enough workers to run multiple shifts. They were already sending buses to neighboring counties to pick up workers each morning and drop them home at night. Then John Rogers saw a PBS show about Miami’s unemployed Cuban population and sent Echiburu to Miami to recruit Cuban workers. The company also began to recruit in Texas border towns again, something it had briefly tried in the late 70s. (Echiburu estimates that maybe a handful of families stayed from that first recruitment effort.) By 1998, B.C. Roger’s “Hispanic Project” had recruited nearly 5,000 workers to Morton and Forest. The project ended as John Rogers negotiated the sale to Koch, and the Latinx influx that came after 2001 was mostly organic; word spread and Hispanic people from multiple cities and countries knew they could find work in the area.

The demographic change since 1990 has been profound. Thirty years ago, Morton was 62 percent white, 37 percent Black, and less than 2 percent Hispanic; per Census data, in 2017 Morton was 43 percent Black, 34 percent white, and 23 percent Hispanic. It had a median household income of $33,983 which was about $27,000 below the national average, and a poverty rate of 22 percent, about 10 percent higher than the national average.

Prior to the raid, the Hispanic community kept to itself, residents told VICE. They worship in their own churches. Their teenagers aren’t well-represented on school sports teams. Instead, they play soccer in the park.

“They don’t trust easy,” said Tanisha Burns, 29, a lifelong Morton resident.

“They paid their own fees or rent or whatever. I’ve never heard a complaint out of any of them,” said a local white pastor, M.R. Reagan. “But as soon as the plants were shut down… then they started reaching for us.”

Most Morton residents seem to feel compassion for the arrested workers’ children. However, many white residents say that while it’s difficult and expensive to immigrate legally, that’s the way it should be done. The Black people in town seem to be less focused on the legal status of their Latinx neighbors and more on the fact that they “don’t bother anybody,” to quote Burns. Burns’s mother works at the plant and called her just after the raid. “She was so upset. Some of her friends were taken, and nobody could do anything,” Burns said.

African-American residents VICE spoke to were also more likely to see the raids through the lens of colonization. “They say they’re not here legally, but really what is legal? Because they took the land from the Indians,” said Diane Henry, 63.

Henry’s granddaughter had been taking extra snacks to school for a few days when her mother finally asked why she was so hungry. The 7-year-old admitted that she was giving the snacks to a friend whose mother had been arrested in the raid.

Saylee Y., a 22-year-old who did not want to share her last name, said her parents would “kill” her if she dated outside of her race, but they do have a close Mexican friend. That friend has been upset at the racist, post-raid sentiments posted on the Facebook pages of other white people she had considered friends. “She has her green card, but still. It’s like they group all Mexicans together,” Saayle said. “Some people did come here the right way, and they did work hard to get where they’re at.”

Both Black and white Morton residents say that the Latinx workforce isn’t taking jobs anyone else would do. “A lot of the Hispanics who aren’t there anymore were deboning”—which is cutting the bones out of the chicken, said Echiburu, who left the plants when John Rogers sold to Koch. Now he’s CFO at another Rogers family venture, the Bank of Morton. “That’s something you have to learn. It’s going to take them a while to replace those people.”

Two hundred people applied for Koch at a job fair following the raid, but some of the new hires quit their first day. “They can’t keep them,” said a longtime Black Koch employee who didn’t want to be named. “The way they work us, they don’t pay us enough.”

“Black and white people didn’t want to work,” another plant worker said. “When all this commotion happened, they gave them a chance to come back, but they’re still not staying. They’re coming and going. Basically they’re saying they’re not going to work this hard.”

Last summer, Koch Foods agreed to pay $3.75 million to settle a class action suit on behalf of Hispanic employees in Morton who said they experienced sexual harassment and racial discrimination. The company was also investigated by the USDA for discrimination against Black Mississippi farmers.

Koch has released statements about the raid and the settlement but has not admitted wrongdoing in either case. Regarding the settlement, Koch “contended… that plaintiffs fabricated allegations of mistreatment” to obtain U-visas. (U-visas provide legal status to victims of crimes who aid U.S. law enforcement.) The post-raid statements claim that Koch leadership was unaware workers were using false documents or that ICE was targeting its plants: “The raid by the government on Koch Foods resulted in a significant disruption of work… The government’s actions amount to serious government overreach under a framework of flawed and conflicting laws.” The statement also noted that the legal actions were targeted towards the individual workers, rather than the company.

Reagan pastors one of the larger churches in town, the multiracial (rare in small-town Mississippi) Strong Tower Worship Center. He said he was “a little bit frustrated with the government side of it, that they came in so forceful, until I got more information of why, that there were some criminals in the area.” He felt “a lot better about our government” when he heard that many parents were reunited with their children the next day. (According to the U.S. Attorney’s office, 300 of the detainees were released on August 8.)

Adam Comis, a spokesperson for the Committee of Homeland Security, hasn’t heard anything about violent criminals among the detainees. According to Comis, Bennie Thompson, the Mississippi Democrat who chairs the House’s Homeland Security Committee, has reached out to both the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice for information on the detainees and is still awaiting a response. But violent crime in Morton is lower than the national average. A longtime sheriff’s deputy said that crime has not increased with the growth of the Hispanic population.

After the raid, there have been fewer Latinx people on the streets and in the shops. The local pharmacist said several customers moves their prescriptions to other towns, but no one knows exactly how many residents the town has lost. According to the superintendent’s office, every one of the absent students eventually returned to school. Sheila Cumbust, pastor of Morton Methodist, estimates that fewer than 10 families have left.

Churches have been at the forefront of the effort to help those harmed by the raids. Cumbust said that $30,000 has already been put toward bills and rent for affected families. Donations have come from all over the country. An emergency food pantry is staffed by volunteers from various churches and has served 216 affected families.

But Cumbest is anxious about when the donations quit coming. “The earliest date on the detention papers we saw was six months out, and the latest we saw was 2022,” she said. “So we may have to do this for two and a half years.”

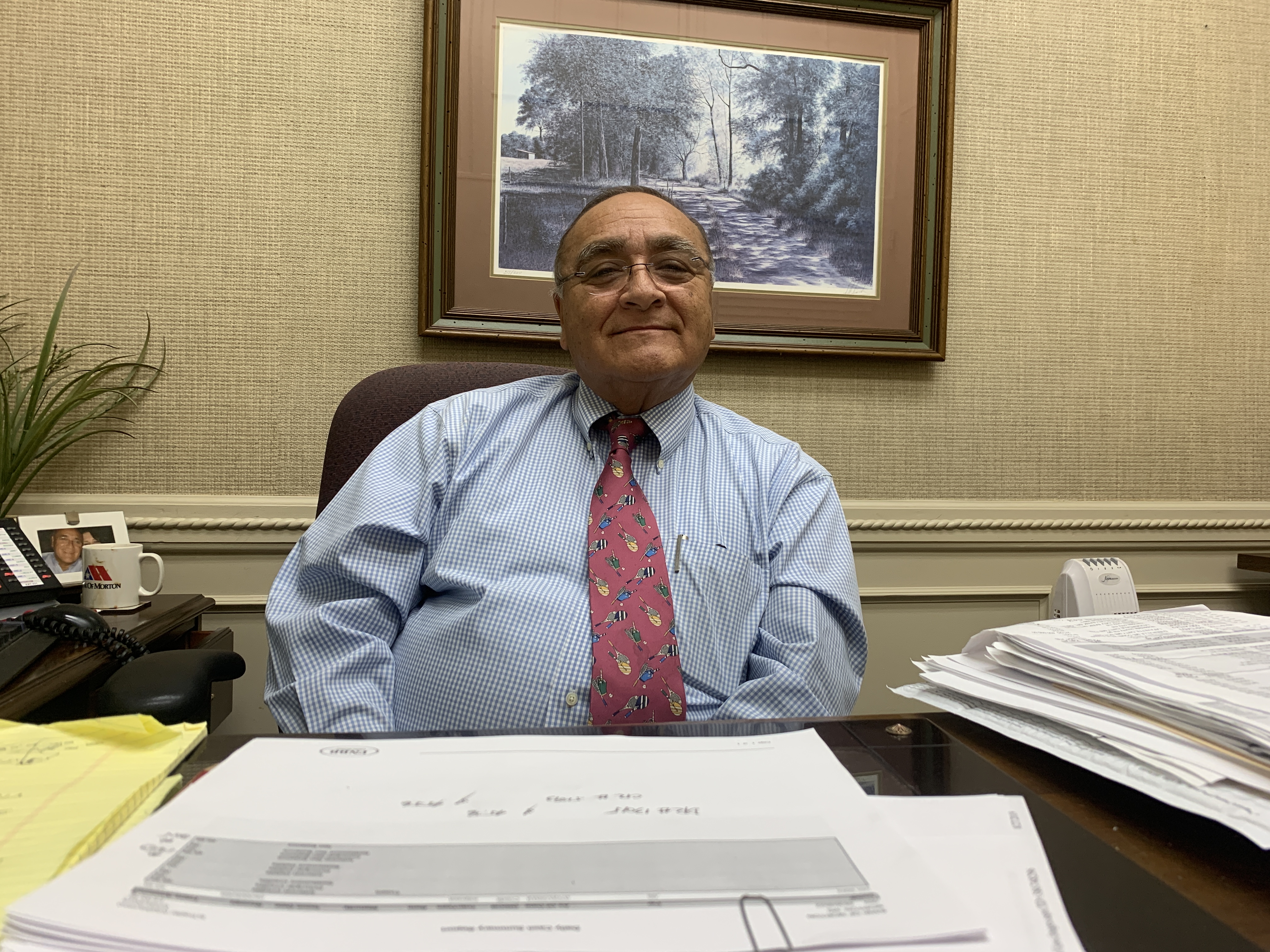

Gerald Keeton, 64, is Morton’s first African-American mayor. “I’m not advocating for anyone to do anything illegal, but I wish there was some way [Latinx workers] could be legalized without having to go through all they have to go through. These are good, hard-working people,” he said.

In October, he will be able to calculate how much tax revenue has dropped. He expects it to be significant, because “these people have become so withdrawn that they’re not coming out.” The town’s Latinx groceries and restaurants have seen a sharp decline in revenue, but so have other local businesses.

Sales have slowed at French’s Pharmacy’s ice cream counter, where the customer base is primarily young Hispanic families. Downtown’s China Wall restaurant has also seen a loss of business.

Greg Sessums, 65, owns a laundromat. “The economy here is based on the Hispanic people,” he said. Sessums supports a path to citizenship for people who have been here for years. He hates that some of his regulars wear new ankle monitors. “If they haven’t caused trouble, give them a chance. Who doesn’t want to do better for your family? I know if my kids were hungry or barefoot, I’d do what I can,” he said.

Sales are also down at the gas stations and convenience stores near the plants. In a town where most businesses seem to be white-owned, these stores, typically owned by people of color, can be a haven for immigrants. Sarah Williams runs the end-of-day totals at the Indian-owned Exxon station, near one of the Koch plants. She says revenue has been down as much as 50 percent.

Sales of Hispanic foods have slowed at Fairway, and Patrick Kelly is concerned about We Care, the thrift store that funds weekly food boxes for primarily senior citizens. “Their main customers are Hispanics,” he said.

Local independent contractors also depend on Koch for their income. “It affects the farmers who grow the chickens, who have borrowed millions to build these chicken-houses and who get paid on production, and the truckers who have bought their rigs,” said Martha Rogers.

The Sunday following the raids, a Latino minister came to Reagan with a computer belonging to his church. He asked to auction it during Strong Tower’s service. Reagan told the minister he wasn’t going to take a computer that the minister’s church uses and needs. “But it does speak to me and tell me that they’re willing to sacrifice, to negotiate, to do whatever it takes,” Reagan said. “They literally don’t have any income.”

Reagan worries about the future. “The backlash is coming, when these families have nothing and the desperation of that is, they’re going to beg first. And my concern is after they finish begging, then what? Do they steal?”

If this sounds like paranoia from a white pastor, who admits that September 11 made him more wary about immigrants, Orlando Buitrageo, 30, a Nicaraguan immigrant who came to the U.S. legally, said something similar: “I think in a couple of weeks it’s about to become a humanitarian something.” He thinks someday people may express their frustration and anger “out on the street. You can’t work, they don’t have enough money to go back to their country.” Buitrageo is working at Kelly’s supermarket and supporting his child and partner, who is waiting for her asylum case to be decided.

For Kelly himself, the raids have been a clarifying moment. Immigration issues have never affected how he votes before, but they will now.

“If I could sit down and have 45 minutes of Donald Trump’s time, just me and him, and no reporters, I could change his mind,” he said.

Cheree is a New Orleans–based journalist covering culture, immigration and the Deep South. You can find her work on her website. She tweets sporadically here.