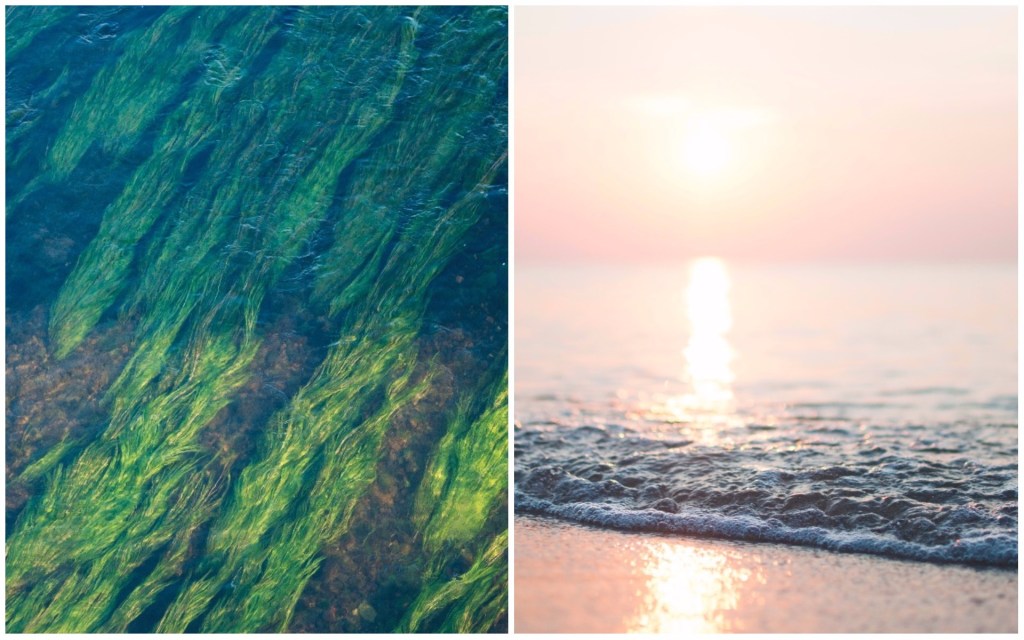

Last October when I was living in Australia, I took a trip to Cairns, a coastal city known as the gateway to the Great Barrier Reef. One early morning, I headed to the dock with three friends for a full-day snorkeling and diving tour of three locations out on the reef. We swam among sharks, sea turtles, fish, and tons of coral—massive colonies of tiny animals called polyps.

At travel agencies and online, you’ll find reef photos flaunting robust coral that’s rich in color—but in reality, the coral didn’t exhibit that bright and beautiful chaos marketed to tourists.

Videos by VICE

Coral bleaching is just one result of a harmful trifecta of changes happening in our oceans right now because of climate change: warming, oxygenation, and acidification, which all threaten life, ecosystems, and biodiversity at sea. “These make a terrible trio of stressors that should be considered together,” says Carol Turley, a senior scientist at Plymouth Marine Laboratory whose research focuses on ocean acidification.

If you see marine life as separate from life on land, you’re mistaken. Ocean acidification hurts ecosystems at sea in ways that also harm human health and safety worldwide. Consider this example: Say you squeeze fresh lemon juice into a glass of water for some added tang. That’ll bring your drinking water’s potential of hydrogen—or pH, a measure of acidity—from a neutral 7 closer to lemon juice’s acidic pH of 2. In a sense, lemon juice is to your water as carbon dioxide is to the ocean.

About 30 percent of the carbon dioxide we push into the atmosphere—through fossil fuel consumption, cement production, and deforestation, to name a few—gets absorbed by the oceans, Turley says. Once in the water, the carbon dioxide morphs into carbonic acid. That has two implications: First, the acid gives off hydrogen ions that leech carbonate, a building block of marine life, out of the water. Second, it lowers the pH of the oceans, making them more acidic.

More From VICE: Our Rising Oceans

Today, the ocean’s pH is dropping at an unprecedented rate. During the last glacial event spanning two thousand years, it dropped only .2 units, says Dwight Gledhill, deputy director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s ocean acidification program. Since pH is a logarithmic scale, a small change in number means a massive change in acidity. Over the past two centuries, the pH dropped from 8.2 to 8.1—a 30 percent increase in acidity—and it’s projected to fall to between 7.8 and 7.9 by the end of the century.

Coastal communities will be, literally, hard hit. Reefs absorb 97 percent of wave energy during powerful storms, according to a recent study in Nature Communications. These natural barriers protect coastlines from severe flooding, erosion, property damage, and loss of life during storm surges.

But high-CO2 waters constantly stress the reefs, and not just through bleaching. Bioerosion—when animals and organisms in the water feed on and eat away at the coral—speeds up in those conditions. Even worse, the reefs have an increasingly difficult time rebuilding themselves fast enough to replenish what they lose to bioerosion since carbonate, the basis of their skeleton, is harder to come by. Take away reefs, and all that wave energy hits the coast.

“You can try to build barriers by hand, but the cost of doing that is just astronomical, Gledhill says. “The absolute value of a coral reef in terms of what you have to do to replace that function is just really, really steep.” Islands and coastal communities where tropical storms rage are especially at risk, but we have vulnerable communities in the United States, too. Researchers from Stanford University found that coastal habitats like reefs and mangroves shield 67 percent of US coastlines. By 2100, they expect a doubling in the population threatened by strong storms.

Back at sea, the survival instincts of fish are disrupted under acidification. Remember Nemo swimming away from the safety of the reef, his home? In a sense, that dazed-and-confused behavior mirrors reality. Many fish use their sense of smell to detect prey, but in waters with high concentrations of CO2, those senses are compromised. Research shows it causes reef fish and sharks to spend 20 percent and 75 percent less time in prey-heavy areas. And just like the coral have difficulty building the reefs, shellfish struggle to build their shells in high-CO2, low-carbonate waters as well. In one experiment, the shell of a sea butterfly gradually dissolved over the span of six weeks.

Since one billion people rely on fish for their main source of protein, these effects could change nutrition around the globe. “In the Coral Triangle, we see people really relying on fish,” says Lisa Suatoni, senior scientist of the National Resources Defense Council’s oceans program, of places like Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. “This could be a really direct effect on human health, because micronutrient malnutrition is an issue in those countries.”

And if any shellfish do make it onto your plate, you could be at risk of high-toxicity shellfish poisoning since harmful algal blooms increase in high-CO2 environments. During harmful algal blooms, the algae release toxins that make their way into shellfish. (Death by lobster roll isn’t the worst way to go, but still.)

“Algae blooms wind up killing two thousand people a year through shellfish poisoning,” Gledhill says, compared to eight deaths by shark attack in 2016. “People worry about sharks. They should be worrying about algae.” If our greenhouse gas emissions don’t let up, we’ll be at increased risk of storm damage, malnutrition, and toxic shellfish. And there’s no quick fix.

“If we stopped emitting CO2 and we had millions of years, our ocean pH would restore itself,” Suatoni says. “Really, this is a problem of speed, the fact that we’re putting so much CO2 into the atmosphere so quickly.”

We can each do our part by reducing local stressors like sewage runoff, pollution, and poor practice in fisheries. Most importantly, we need to reduce our carbon footprint and encourage policy-makers and major industries to commit to the cause.

“The ocean is key to life on Earth,” Turley says, and at this rate the future is bleak for many ocean ecosystems, including those that provide food, livelihoods, and coastal protection for hundreds of millions of people.

Read This Next: Why Living Near Water is Good For Your Mind