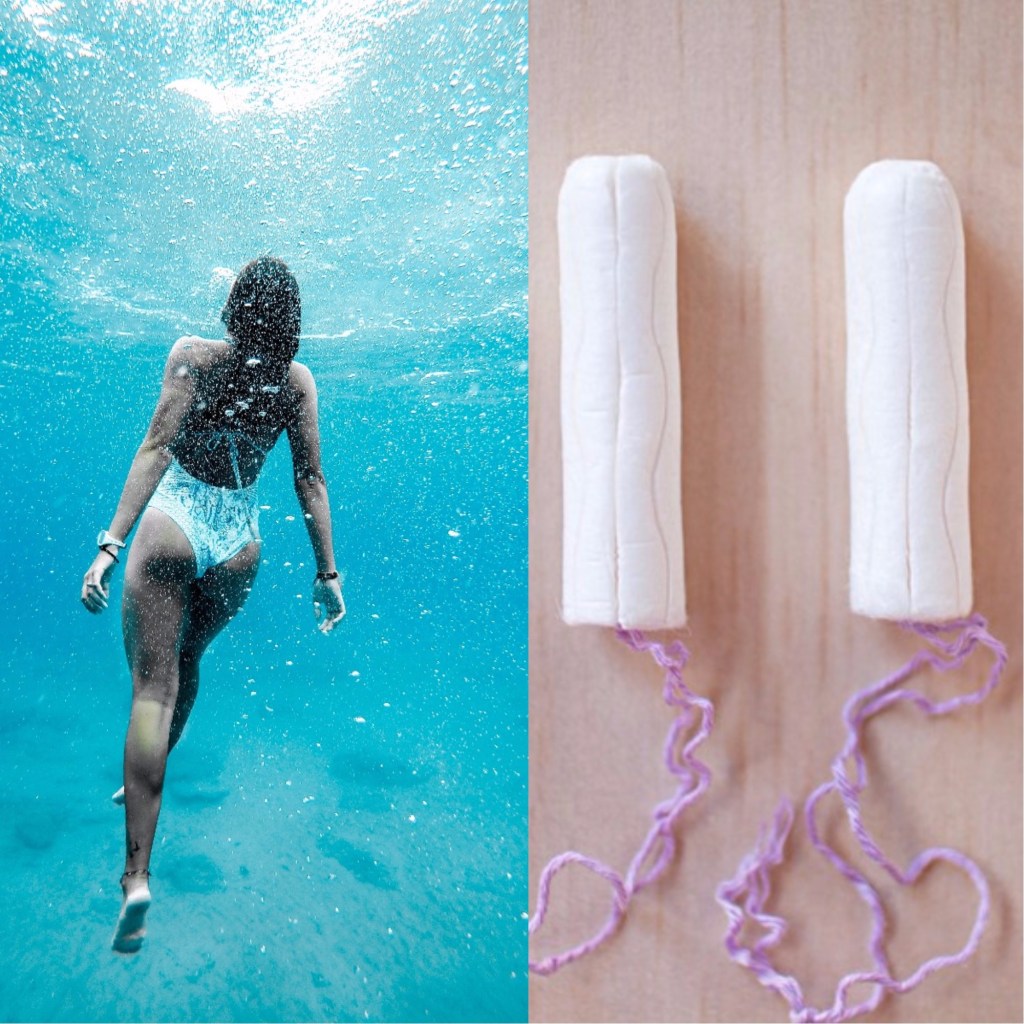

The Situation: It’s beach season and my friend has been invited to a lavish resort in the tropics. She figures it’s the perfect time to bust out that new bikini, but she forgot her tampons back home. So what if Aunt Flo’s in town?, she shrugs. Life is short—plus, she read somewhere that your period actually stops in water. In total honesty, my “friend” doesn’t have the best track record when it comes to decision-making. If she goes swimming à la crimson tide, will she leave a bloody trail straight out of a scene from Jaws?

The Facts: Your friend can rest assured knowing this (mercifully) won’t happen. There is some truth behind her flow’s mysterious disappearing act. While it may seem like her period has magically stopped once she hits the pool, what’s actually happening comes down to plain old physics.

Videos by VICE

How this works is somewhat enlightening: Although the coating of her uterus continues to shed—when she’s fully submerged in water, the pressure counteracts the gravity of blood exiting her vagina. “It’s not that you stop bleeding,” says Jessica Shepherd, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and U by Kotex Partner. “It’s more that there’s pressure to stop blood from flowing out.” And this same trick applies when we’re immersed in a bathtub or any other large body of water.

Still, your friend’s fear is real. Periods, which are made up of blood and womb lining, can last around three to seven days, with women typically losing an average amount 30-40 mLs of blood during their menstrual cycle—who’s to say all that flow won’t make its way out and cause some embarrassing water works?

The Worst That Could Happen: Just because gravity is on her side, doesn’t mean your friend’s totally off the hook. Any false move could pose a risk: If she laughs, coughs or sneezes—a small amount of blood could be released, which can be especially worrisome for heavy bleeders who make up a quarter of the female population, and can lose up to 60 ml or more menstrual blood in a given cycle. But as Shepherd points out, the real concern isn’t so much what happens inside the water as what happens once she exits. “I would be more concerned about that part of the activity, [because] you don’t have the counteraction with gravity,” she says.

What Will Probably Happen: Your friend can breathe a sigh of relief. Sort of. Shepherd says that the ratio of water should dilute any blood so that it probably won’t be visible, especially if she’s at the beginning of her cycle when bleeding tends to be lighter. “If someone’s not hemorrhaging (heavy bleeding with blood clots), there’s a very small chance that it would be noticeable to others,” she says. More importantly, it’s not likely that your friend will endanger anyone’s health—swimming pools already contain small traces of bodily fluids like urine and sweat, and are (thankfully) treated with chlorine to guard against these questionable amounts.

“There are a lot of misconceptions around what you can and can’t do during your period, and because of this, a person might feel they should forgo swimming altogether,” Shepherd says. But, she stresses, it’s quite the opposite: “We actually want women to [swim] during their cycles so they can minimize cramping”. Painful periods (caused by contractions in the uterus) can prevent people from enjoying everyday activities that would otherwise help reduce the cramp-like, dull, throbbing pain in their lower abdomen. And we’re not just talking minor discomfort here: Some patients have compared their period pain with having a heart attack. The continuous flow of aerobic activities like swimming can help alleviate some of these symptoms, Shepherd says.

What your friend should do: No need to let a little blood ruin her good time. The simplest solution is the most obvious: Using a tampon or menstrual cup can easily take away that barrier of anxiety, Shepherd says. Pads and pantyliners aren’t a good option because they absorb water and become ineffective once she’s in the water. If your friend is hell-bent on swimming au naturale—sans tampon or menstrual cup (not recommended for obvious reasons)—she should try layering up with a pair of shorts can also offer her that extra protection when she’s getting out of the pool. Shepherd advises the extra gear, if available, to avoid a potentially Carrie-style exit.

Correction: A previous version of this article states that Jessica Shepherd is professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also a U by Kotex partner.

Read This Next: The Period That Wouldn’t Quit

More

From VICE

-

MysteryVibe -

(Photo by sdominick / Getty Images) -

Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist streamer and US social media pundit, appears to mace 57-year-old Marla Rose, a 57-year-old on his doorstep on Sunday, November 10 (Imagery courtesy of Marla Rose) -

VICE