GARAGE is a print and digital universe spanning the worlds of art, fashion, design, and culture. Our launch on VICE.com is coming soon , but until then, we’re publishing original stories, essays, videos, and more to give you a taste of what’s to come.

“I just follow the roads of pictorial power,” declares André Butzer grandly as he walks me through his solo debut at Nino Mier Gallery. Though the Stuttgart-born painter became an LA fixture in the early aughts after a series of shows with Patrick Painter, he hadn’t set foot in the city since 2010. This was the year he began exhibiting his all-black “N-Bilder” paintings, which he makes at a vast studio housed in a former airplane factory in Rangsdorf, an hour south of Berlin. However, in his return to LA for the Mier show, Butzer’s no longer the rebel his earlier paintings once suggested. Dressed in a restrained ensemble of blues and grays, peering through delicate glasses, and with his hair cropped tight, Butzer is the living embodiment of his now-somber paintings, brimming with an understated power.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, and the paintings change slowly,” says Butzer of the “N-Bilder” works. After eight years of making almost nothing else, they have allowed him to revisit his early forays into figuration with renewed confidence. “They taught me that it’s about making a total piece,” he explains, “not just things here and there.”

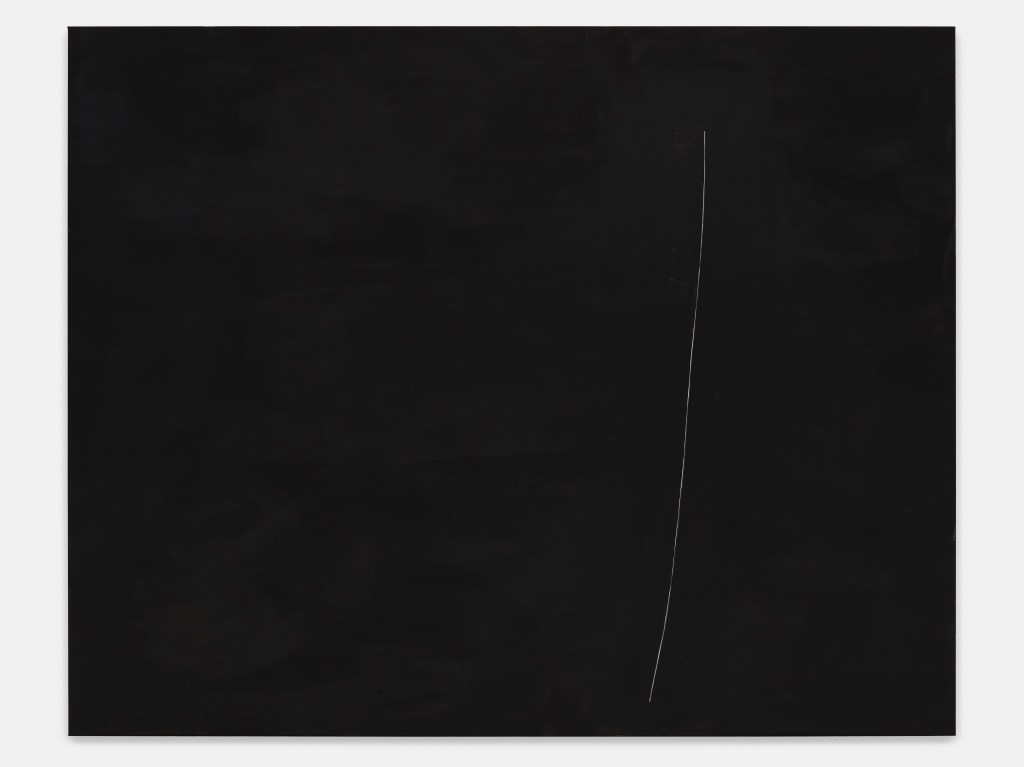

Mier’s project space on Santa Monica Boulevard is dominated by a pair of massive, atmospheric “N-Bilder” works from 2017, each a black field traversed by an atomized white arc. Opposite these is a painting of a radiant female character that emerged from Butzer’s “Nasaheim” series—a maximalist narrative mashup of future tech and retro façade rooted in the concept of the heim (house). In Mier’s primary space, Butzer shows a series of smaller, tightly controlled “N-Bilder” canvases from 2016, their brilliant white lines appearing to shift perspective with the viewer’s movement. While the “N-Bilder” series began with a rigid geometry of right angles and squares, they’ve now begun to incorporate glimmerings of tonal depth. “I’m now trying to destroy the white,” growls the artist. “I hate white.”

GARAGE: What made you return to LA for this show?

André Butzer: I met Nino through my dealer in Berlin, Max Hetzler, and he called me and said, “You should do a show with Nino.” And that was it. I met him a little later and found out that he’d collected my work. I was proud to meet someone who’d supported my art even though we’d never met.

Where did the show start for you?

Originally I wanted to show only black paintings because I thought this would be the right way to come back to the city, with paintings nobody knew.

What do you call this female character you’ve been painting recently?

This is a “golden woman.” But I’ve made many paintings of women before.

Is it fair to say that the grey paintings led to the “N-Bilder” series, and that the “Nasaheim” works led to the appearance of this female character?

Yes, I always try to find the pictorial origin of what I do. But finding an origin is like trying to go back to a place that you’ve never actually visited.

Where did your very first images come from?

When I first started out I made colorful impasto paintings featuring alien figures with cartoonish expressions. I really overdid what I thought an extra-terrestrial expressionist painting might be. But I also integrated all kinds of other topics, motives, titles, references to art history, brand names . . . It took me a long time to get away from these things, and then to rebuild them.

It’s almost as though you took narrative out of your paintings.

I would say I maximized the pictorial forces. But pictorial forces can appear only if pseudo-narrative is absent. I think don’t think narrative is part of image making, but I allowed for it in the early paintings because I had to find out what to throw out.

Videos by VICE

Who or what made you want to become an artist and start to build this world? Your family? My father worked for IBM, but he was sick with multiple sclerosis almost his whole life. He worked in semiconductor development and I later used lines derived from images of semiconductors in my grey paintings. My father’s tragic circumstances made me decide, as a young man, not to follow his path by working for the same company. This was in Stuttgart, the home of Porsche. It’s a nice city, but it’s very industrial.

What was your first exposure to art?

I think when we went with the school to the museum in Stuttgart, when I was 14. I saw a Fontana, a Baselitz, and some other things that I didn’t like straight away, like a Gerhard Richter seascape. I had no contact with any kind of art through my family, but I felt I could do something different from what my father got sick from, that I could save myself from this tragic tendency of industrialism. Painting was a way for me to heal, but also to attack. When I was a little older I understood that I had to go where the enemy was and not attack from the outside. I had to embrace negative things and integrate them into my art, allow it to come in and then find ways to throw it out.

The earlier sci-fi expressionist paintings seem to embrace this narrative, this chaos and sickness. Do you feel like you’re a hitman of sorts?

I do feel like I’ve tried to erase those things. For eight years now I’ve made almost only those black paintings. I’ve tried from time to time to paint a figure painting, but I wasn’t ready to accept it. Now I feel free. In my previous paintings there is a certain power that’s unsure of itself, a little blind.

By stripping your paintings down to sober gestures, you can amplify what’s truly necessary.

Yes, things become elemental. The “N-Bilder” series reminds me you have to control the totality of the painted field. Before I started to make those works I was like the drunken young guy running crazy against the world. That’s over now.

Do you consider your early paintings political?

I would say post-political, because I was never on the side of good or bad. In art you can’t be moral. So I wouldn’t call them political because politics is about evaluation. I can’t change things immediately but I still have to go on, so I believe in the power of art. Art’s never obvious. Truth is always something that’s always partly hidden. Painting has no surface at all in general. It’s about depth and something in between, but not about the surface. It’s also not about motivation.

Do you think it’s hard to be a painter right now, in this politically fraught moment with its powerful corporate culture and creep toward fascism?

I think it should always be hard. I want it to be hard because I want people to think it’s not just something they can do like a job. But I have nothing against more and more people becoming artists. Maybe it’ll save the world, maybe it’s part of the world being destroyed, nobody knows. But for me it’s not easy, it’s not a “fun job.” I feel very unsatisfied and insecure because I don’t have a consistent perspective. One minute I like a painting and the next I’m depressed.

Try being a writer . . .

I do try to be a writer in between things. I write little poems. But I do it on a totally different basis, at home, not in the studio. Just before I came here I made a text. A magazine in Berlin asked me for something, so I made a text that reads like a philosophical essay, but it also like a prose poem. But they took it but they changed it. It was a nightmare. Reality strikes back . . .

Returning to the “N-Bilder” paintings, where are you now with the series?

I’m at some kind of new beginning. I was trying to find the so-called destructive element, and to begin again from there. The destructive element is a very positive element. It has to do with balancing out life and death. It took time, but I can say I’m kind of a beginner again. Painting has to be about light, revelation.

So you’ve freed yourself by not having to think about making the moves, you just make the moves.

Yes, it’s not about thinking them out. There’s a rule in painting: light has a proportion. Without it, a painting would be proportionless. And it allows you to begin.

So by painting black paintings, you’ve taught yourself to see the light?

In a sense, but it’s a dark light. It inhabits the painting so that the painting itself becomes a source of light. It’s the creator of light and a hint at the origin of life. Life and light are deeply connected terms. I’m a big fan of this overdetermined term matrix, because matrix loosely translated is mother. I think of painting as the origin of life.

We’re always inheriting, but you can’t just take on influence for free. There has to be some thankfulness.

Who are you thankful to?

My thanks go to Giotto, Titian, Rembrandt, Veronese, Tiepolo, Mondrian, Matisse. But then I’m very quiet about things after Matisse.

What about Albert Oehlen?

I’m thankful to him because I know him on a personal level. I helped him in his studio for a while in the mid-nineties, and he was my first collector. He’s a very intelligent guy, and not only because he bought my paintings! I think he’s a great artist, but I wouldn’t thank him for his painting. I can’t.

Why not?

I’m very critical of contemporary painting. It’s an era that I don’t really believe in. I’m in it as a living person but I don’t feel part of it.

Can I ask you about the “Nasaheim” series? Didn’t that come from a visit to Disneyland? The title “Nasaheim” is an invention, but it did come from the name Anaheim, where Disneyland is. When I was there in 2000 I thought it was great that it was so far away from home, but had a name with “heim” in it, because heim means home in German. The city is a mess, but I was interested in Disney. My friend the sculptor Björn Dahlem and I decided it should be called “Nasaheim,” like the next frontier, because it’s got the frontier spirit and it’s on the west coast. To say “Nasaheim” in German is funny. It’s like saying there’s a home where NASA is, or a shack with NASA inside. It’s interesting too because you have NASA representing cosmic travel and heim representing closeness, warmth, and also maybe something hidden, like the truth.

It’s interesting that Disneyland was based on Tivoli in Copenhagen. I was actually just there and made a joke to one of the ride operators like “They wouldn’t do that at Disneyland,” and she shot back at me “We’re much more evil than Disneyland!”

Disney is almost like a second death, or a prolonged life in death.

This was debunked, but it was once thought that Walt Disney was cryogenically frozen, and there’s a notion that living on in that way is basically life in death, or like being a zombie. You’re creating a sort of hell . . .

That’s reflected in my view of LA. It’s like death in the sunshine.

Do you like LA?

I’ve become a stranger to it because I haven’t been back in seven years and the city’s changed. I live an hour south of Berlin in the countryside in Rangsdorf, and I’ve been there for 11 years. I have several buildings and one I live in. And I have 140 trees. I counted. So it’s a good place and it’s still close enough to Berlin if you want to go. But I stay home.

What are you working on next?

A big show for a museum in Japan, two hours outside of Tokyo. I’m showing black paintings only.

Do you plan to make any more figurative work?

I’ll try. The figurative paintings teach people to love the black paintings more than they would without. It’s strange because the female figures in them are like witnesses. They witness the light in the black paintings and they show it to the viewer. They know about truth because they’re part of it. Women know more about the origin of life than men.

It’s serendipitous that you’re showing these paintings during the eclipse.

I was there. I went to Oregon.

Of course you can’t look at an eclipse directly, you need a filter. Perhaps it’s the same with your paintings. You can’t take them in in at a single glance.

No, you have to find a context. I felt the moments before the eclipse were the best, when the light became unnatural and brown. We were alone in a field and while we had total darkness, at the same moment we could see the sun reflecting off the glacier on Mt. Hood. That was a good moment. It made so much sense to me that this happened along with my so-called LA comeback. I’m thankful because I’m not alone. As an artist you can’t be alone.

Has this experience in LA changed anything for you?

Yes, I’m trying to be optimistic. I have a tendency toward depression but I think I will go on and be happy.

Michael Slenske is a Los Angeles-based writer and editor who covers art, culture, and travel. He is the editor-at-large of CULTURED and LALA.

“André Butzer” is on view at Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles, until October 7.

“Back to the Shack”, curated by André Butzer, is on view until October 14 at Meliksetian Briggs, West Hollywood.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshots: Larian Studios, THQ Nordic -

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: Square Enix -

Collage by VICE