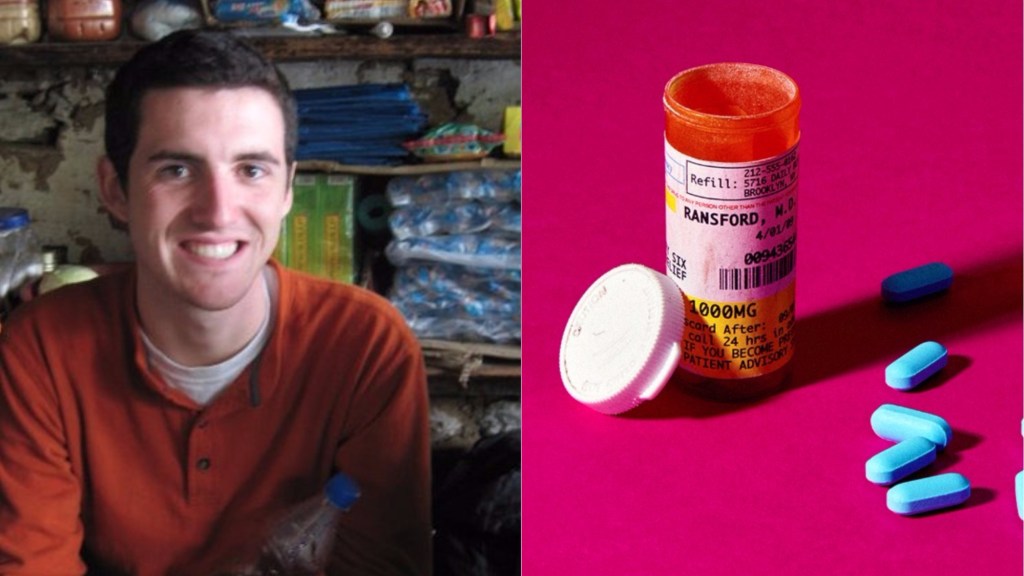

I was addicted to Xanax. I’d never thought I would say those words aloud but when studying abroad in New Delhi, India as a 21-year-old back in 2011, I knew I’d officially gone over the edge. I’d been a binge drinker since I was 15, and I’d spent a month in inpatient rehab when I was 16 after twice being hospitalized for alcohol poisoning. But, with alcohol—which I eventually gave up, years later—I was convinced that though I lacked control, I was not technically addicted. I could, after all, go days without drinking.

Xanax was a different type of beast: If I didn’t have it, I felt like I was going to die. Xanax—a benzodiazepine under the same class as Klonopin (clonazepam), Valium (diazepam) and Librium (chlordiazepoxide)—is used to treat panic disorders, insomnia, seizures, alcohol withdrawal, and anxiety. I’d started taking it after a doctor prescribed it for panic attacks one month into my six-month study abroad program. While “Xannies” are a recreational trend on college campuses, I imagine many students to get them prescribed if they’re experiencing anxiety while away from home for the first time. After taking it multiple times a day for months, I knew I had to stop. It was not about using it as treatment anymore.

Videos by VICE

When I woke up, I needed it right away; if I wanted to fall asleep at night, I had to have one last pill. Throughout the day, pills were popped frequently. If I didn’t have Xanax, my body would react. I’d get a headache, or feel my heart palpitate, and I’d be utterly convinced that I was having a brain aneurysm or a heart attack. The only thing that made me feel better was taking Xanax.

I had become a walking ghost. I was sedated, constantly, and mentally removed. When I drank in addition to taking the pills, it was literally like I was roofie-ing myself; I would slip into a coma-like state. When I my Xanax high faded, my palms would start sweating, and I’d feel nauseous.

After four months of months of daily Xanax use, my anxiety was only amplified ten-fold. Where my panic attacks had been sporadically debilitating in the early days of my program, my life was now completely defined by, and dependent upon, maintaining my high. I knew I couldn’t live this way. I knew it had to stop.

So, I tried to wean myself off. I made my doses smaller over the course of a few days, and then I totally stopped. I was afraid I would take more Xanax if I had a supply, so I didn’t refill my prescription. I was convinced this was the only way I would be okay. I was wrong.

Twelve hours after I stopped taking Xanax, I was in distress. One day, I tried to leave my apartment to attend my classes, but I could barely make it down the street.

Cars and auto-rickshaws zoomed by, people and cows wandered past, but all I could focus on was what was happening to me. I knew I must look crazy, but I couldn’t pull it together. My heart was palpitating, my joints were locking, and I was more nauseous than I had ever been. I was coming in and out of a dissociative state, where I didn’t feel quite attached to my physical body; it almost felt like I was watching myself fall apart. I felt like I was floating above myself on a busy New Delhi street, on the verge of death.

More from Tonic:

I tried to tell the friend I was with how I felt, but I couldn’t. I was sweating profusely, and throwing up on the side of the street.

“I’m dying,” I told her.

So we rushed to the hospital, where I sobbed and threw up more. I begged the doctors to save me, and eventually they injected me in the butt with a sedative.

“Am I going to die?” I asked.

“No,” the nurse replied, blase, as though death were a thought that never should have crossed my mind.

My question wasn’t outlandish.

“Like with alcohol, you can die from Xanax withdrawal,” says Anna Lembke, program director for the Stanford University Addiction Medicine Fellowship, and chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. Lembke, who authored the book on the prescription drug epidemic, Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop, focuses on treating patients who have become addicted to prescription drugs. “The problem that we see is there no evidence for daily, long-term use for Xanax to treat anxiety or insomnia,” Lembke says. “And yet, we see many patients who are put on these medications for months or years, especially among the elderly.”

Lembke explains that substances that release high amounts of dopamine swiftly tend to be more addictive, “especially for those who are vulnerable to the sedative effect.” She adds, “Xanax is one the most addictive benzos because it’s very potent and has an immediate response, so it tends to change way person feels faster.”

Similar to opioids, there has been a rise in benzodiazepine overprescribing, misuse, and addiction during the last three decades, she says. Where rates of opioid overprescribing have plateaued or gone down a little bit since 2012, the rate for benzodiazepine overprescribing has continued to climb. Though Lembke says we’re already at a point where benzodiazepine over-prescription could be considered an epidemic, she said she is skeptical it will be recognized for what it is—a hidden crisis—because of what she called a crude outcome measure: Death.

“The reason everyone is noticing opioids is because people are dying,” she says (Lembke has served as an expert witness in litigation against drug manufacturers). “Opioids have this unique property where they suppress respiration and heart rate, and people collapse or become unconscious and stop breathing.” While we as a country fear opioids as the prescription drugs we’re most likely to get addicted to, this doesn’t mean benzodiazepines can’t lead to death: When mixed with opioids or alcohol, they can raise the lethal risk by exacerbating respiratory and heart rate suppression.

In fact, opioids are involved in an estimated 75 percent of overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines. And even though people don’t typically die from daily consumption of benzos on their own, Lembke says being addicted to them could be a major hit to a person’s quality of life. There are plenty of negative consequences including cognitive decline, depression, restlessness, agitation, seizure-like symptoms and increased fall risks.

Beyond behavioral interventions such as exercise, therapy, and mindfulness meditation, Lembke’s suggestions for treating insomnia and anxiety without benzodiazepines were similar to advice I received when I was medically supervised to beat my addiction: Using the most common group of antidepressants, SSRIs.

“SSRIs tend to work well to mitigate anxiety,” she says. “Prozac won’t eliminate panic attack, where Xanax would, but if you take Prozac daily it will lower anxiety so you won’t get panic attacks.” Plus, although benzodiazepines provide greater relief from anxiety symptoms during the first two weeks of use, antidepressants show equal or better relief thereafter.

After the hospitalization, I continued taking Xanax and returned to the US the following week. I was honest with my psychiatrist about my addiction, and she helped me wean off of Xanax and go onto Zoloft (though I probably should have gone to rehab). While the transition was challenging—the Xanax had been such an immediate fix to panic attack—the Zoloft did in fact help me lower my underlying anxiety.

When I finally stopped drinking, years later, I realized how much alcohol had been exacerbating my anxiety and panic attacks. Today, I’m on Wellbutrin, and don’t drink or recreationally use drugs. And though I still get anxious from time to time, I haven’t had another panic attack. You don’t need to get off psychiatric drugs completely to find your equilibrium, but finding the right one—and taking it judiciously—could mean the difference between life or death.

Update 12/5/19: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that Anna Lembke served as an expert witness in drug-manufacturer litigation.