“All the things that I used to do I still do,” the novelist Richard Ford, 73, tells me. “Still play squash, still ride my motorcycle, still lift weights, still do pushups…”

“Still listen to Springsteen,” I offer, in reference to his review of the Boss’s memoir for the New York Times.

Videos by VICE

“Damn right, still listen to Springsteen, for sure.” Ford is the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of eight novels, four story collections, one screenplay, and now a memoir, but of his first foray into rock criticism, he says, “I felt about as capable to write that as I’ve ever felt about anything.”

Ford is a longtime Springsteen fan, and the characters in a song like “The River” (“I got a job working construction / for the Johnstown Company / But lately there ain’t been much work / on account of the economy”) are basically the people in Ford’s earlier stories. His most beloved creation, Frank Bascombe, lives in Haddam, New Jersey, a fictional town squarely in Springsteen territory. Indeed, Independence Day, the second and most-celebrated of the four Bascombe books, was named for “Independence Day,” Bruce’s song about his father. Ford—nomen est omen—is as uniquely American and easy to misinterpret as “Born in the USA.” He hunts (and calls the NRA “a domestic terrorist organization that tacitly supports the killing of children”); he fishes (and Raymond Carver memorializes the incident in verse); he obsesses over home ownership (and writes a novel about a real estate agent who wins both the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner Award).

Watch: VICE Meets Norwegian literary sensation Karl Ove Knausgaard:

“I like not writing a lot more than I like writing,” he says. “The only trouble is that when I don’t write for a long period of time, my wife tells me I’m not that much fun to be around.” Ford and I are in the apartment that he’s rented near Columbia, where he teaches a literature course every winter semester. We are here following the publication of his new memoir, Between Them: Remembering My Parents. Ford’s fiction is filled with masterful depictions of the unremarkable triumphs and standard losses of regular people, and Between Them is his attempt to memorialize his parents’ ordinary lives without making them seem secretly extraordinary.

“My father was a typical human being, in so far as he caused very little to happen,” Ford says. That he and his wife are the subjects of their son’s latest book is “not because he was important in the world, but because I felt like, given that he had a son who was a writer, to not notice him would have been such an opportunity missed. Not even because he was my father, but just because he was a human being.”

Ford is mildly dyslexic, and he tells me, “I hadn’t read a book by the time I got out of high school.” He has the reverence of someone who found literature a little later than most. He reads slowly; a side effect of this is his attention to the poetic and sonic qualities of language, and his replete supply of quotes from famous writers. He seems to relish his role as a bit of an outsider to the culture.

“I got into as much trouble as it was possible to get into, just about,” he says of his rogue teenage years. “Breaking into houses and stealing cars and breaking into businesses and stealing safes and breaking into friends’ houses and stealing their parents’ gun collections.”

He describes it so casually that it seems almost quaint, as if firearm theft was a typical hobby for boys in the late 50s. “No, it was transgressive,” he says. “We knew it was transgressive. But now, with all of these various media, whereby everybody gets a say about everybody else all the time, a certain kind of proportion is lost. So if two little 16-year-old boys break into a house, it suddenly becomes Dylann Roof. If you have a slightly controversial view, all nuance is lost. Only extremes matter. So what I do is just put my fingers in my ears. I don’t do Facebook, I don’t do social media, because I don’t give a shit.”

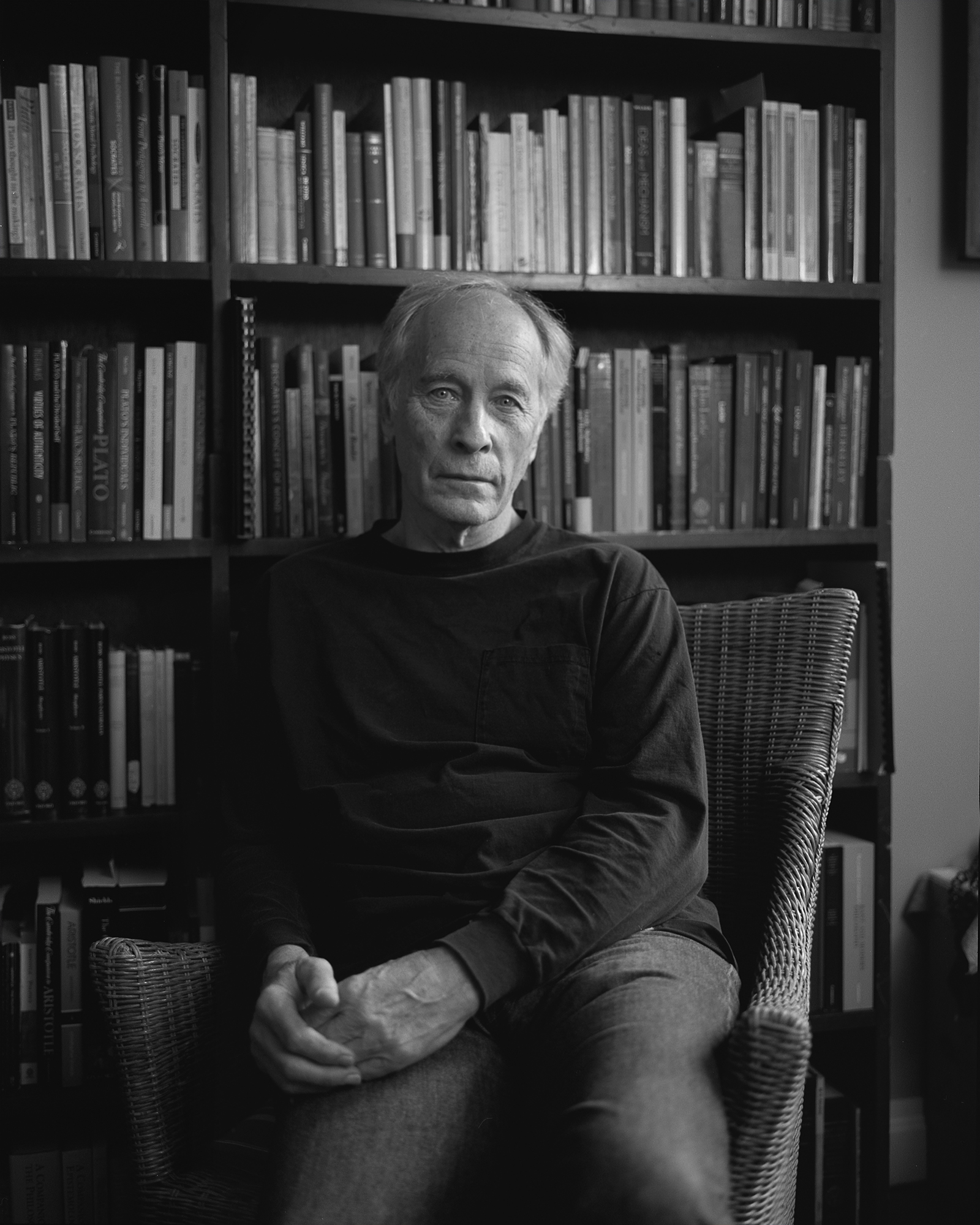

Richard Ford at home. Photo by Heather Sten

Ford has worked hard to “think originally,” as he puts it—to convey subtlety and express non-traditional views. He’ll go years taking copious amounts of notes about characters and place until a book becomes “inevitable.” Ford’s works can be sorted in any number of ways (chronologically, novels vs. stories, geographically), but it more or less comes down to the Frank Bascombe novels (The Sportswriter, Independence Day, The Lay of the Land, Let Me Be Frank with You) and everything else. After two commercially unsuccessful novels—1976’s A Piece of My Heart, a Southern gothic filled with drifters and violence, and 1981’s The Ultimate Good Luck, a neo-noir about a pent-up Vietnam vet—Ford was facing a make-or-break moment. With the release of The Sportswriter drawing near, he says his agent told him, “Ford, if this book doesn’t work, you are toast.” It worked.

The Sportswriter marked a dramatic shift in tone and content. Frank Bascombe is not a dangerous drifter in a desolate landscape. He’s a divorced father with a son who died from Reye’s. He’s a failed novelist, now a sportswriter, living in a suburban New Jersey home that’s fortuitously appreciated in value. The novel is nearly 400 pages of what amount to Frank’s thoughts on life, love, and living. Despite all this, it’s very funny. We spend Easter week with him as he travels on assignment, visits his new girlfriend, fishes with the Divorced Men’s Club, sees his kids, and fills us in on everything that’s happened in his life up to this point. It’s the kind of structure that, with a less exacting writer, could have gone very wrong.

As Ford explains it to me, after his first novels failed to find an audience, he realized he needed to do something different. “The two that came before it didn’t do for me what I felt I needed to be able to do. Namely, to get as much on the page of what I could do as a writer as humanly possible. I needed to find a vessel which would take everything I could do: be smart, be funny, be poignant, be observant, be au courant.” Frank becomes one of those characters where it doesn’t really matter what’s happening, just as long as Frank—or, really, Ford—is the one telling you about it.

In two brief sections written 30 years apart, Between Them gives a sense of how Richard Ford the dyslexic delinquent became Richard Ford, chronicler of the American everyman. It does this by both telling the story of his parents’ lives and depicting an earlier time in American history. “Gone,” the half about his father, opens the book. It’s the stronger half, for a few reasons. Ford wrote the section about his mother in 1986, not long after her death; in the intervening decades, he’s become a better writer. This is not to say the part about his mother is less than accomplished, but writing about his father presented more challenges, which makes the memoir’s achievements all the more remarkable.

Ford’s father, Parker, was born in 1904 in Atkins, Arkansas. He met Edna Akin around 1928. They married 15 years before she became pregnant with Richard. During this time, Parker worked as a traveling starch salesman, where the young family “[tootled] around the South in my father’s company car, drinking and having a good time.” They eventually settled in Mississippi, where Edna stayed home with Richard. Parker kept his job, leaving for the week and returning home Friday nights. When Richard was 16, Parker had a heart attack and died in his son’s arms.

“In retrospect, the advent of death can cast a too dramatic light on the events leading toward it,” Ford writes. It was a normal, happy childhood, and “hardly an hour goes by on any day that I do not think something about my father.” To quote the remarkable ending out of context would take away from its punch, but it’s as good of a tribute as any writer could hope to leave a beloved parent.

“Writers are just ordinary people. With the proper amount of application and with high enough aspirations and ambitions, even an ordinary person can do something that’s extraordinary.”

I asked Ford why he finally wrote about his father now, so many years after writing about his mother. He told me that it was never a question of if he would write about his father’s life, only a matter of finding a way to do it.

“In the intervening 30 years, I understood that writing about my father was a special kind of problem. He was gone for much of the time when he was alive, and then he departed life in 1960, and many years have gone by since then. I was addressing the problem of: How do you write something about someone who was mostly not there? I had a conceit for it: to write about absence as if it were a kind of presence.”

He describes his parents as “sort of like Chekov characters: You wouldn’t notice them if you met them in the world. That’s been an interest of mine as a fiction writer all my life.”

When Ford writes that his father “was a man who took life randomly as it came, and was good at avoiding what he didn’t want to think about,” that’s also the perfect summation of Frank Bascombe’s philosophy.

“I think one of the interesting things to me about Frank Bascombe was his willingness to kind of descend on the rung of important jobs, whereas the standard expectation among Americans is that we are always climbing,” Ford said. “Frank was trying to find a rung on the latter where he was comfortable. And my father was that kind of man. He hadn’t gone down in the world, but where he finally noticed himself was in a place where he was completely comfortable.”

Ford at his desk. Photo by Heather Sten

Ford’s previous work is the reason people will read Between Them, but his career goes unmentioned in the book. He says he didn’t want to steal the attention away from his parents: “My life would in conventional terms make their lives seem diminished, to make their lives seem to be a run up to my life, which is not the case.”

Ford is clearly proud of the success he’s had, of a life lived vigorously—of riding motorcycles in the Alps, fishing with people like Raymond Carver and the brothers Tobias and Geoffrey Wolff, and getting awards from the King of Spain. But when I ask him if he likes being interviewed and speaking to crowds, he says he does, but, “It’s not a star turn for me.

“Writers are just ordinary people,” he insists. “With the proper amount of application and with high enough aspirations and ambitions, even an ordinary person can do something that’s extraordinary. The people who like writing and might tend to revere writers are better off to know that we’re just regular, just the same as everybody else.”

Follow Hanson O’Haver on Twitter.

Between Them: Remembering My Parents by Richard Ford is available in bookstores and online from Ecco.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Neil Lupin/Redferns -

(Photos by Peter Dazeley; Renata Tyburczy / Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Image: Paramount Pictures