If ever there was a time to unleash your inner Lisa Simpson, this is most assuredly the moment, as perpetually endangered federal funding for education and the arts is set to be defunded out of existence if Donald Trump gets his way. The president’s proposed budget, revealed on Thursday, would eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Created in 1965 by President Lyndon Johnson to “foster and support a form of education, and access to the arts and the humanities, designed to make people of all backgrounds and wherever located masters of their technology and not its unthinking servants,” the programs are a lifeline for American arts and culture as we know it.

Trump’s budget is going to be opposed by Congress for all sorts of reasons, but the battle over the NEA and NEH will likely be one of the most intense, even though the two agencies combined take up less than .002 percent of the federal budget. Arts groups across the country are mounting their offensive, but as the debate begins, it’s worthwhile to remind ourselves of the stakes.

Videos by VICE

A staggering number of musicians, writers, curators, and filmmakers have depended on federal support at some point in their careers. We’re not talking about a marginal urban elite or, to quote James Joyce scholar Spiro Agnew, an “effete corps of impudent snobs,” but a crucial backbone of world culture, which has an output that is interlaced with our sense of identity and emergence as thinking, feeling individuals.

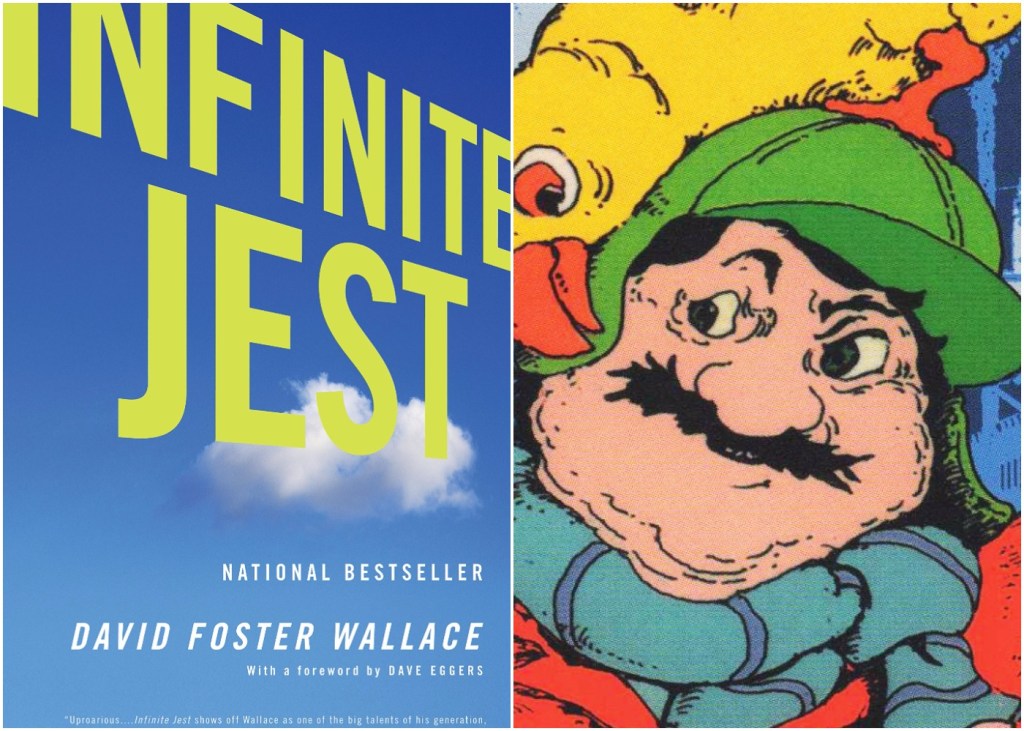

When you wake up to the DVD menu of an award-winning Ken Burns documentary, that’s NEH funding. When you take a selfie next to installation art by Glenn Kaino in Indianapolis or see an opera based on Orson Welles’s broadcast of The War of the Worlds in LA, that’s NEA funding. When you scan your Tinder hookup’s bookshelf for Infinite Jest, that’s NEA funding. When you hide out at New York’s Film Forum in between job interviews, that’s NEA and NEH funding. When you watch Monty Python and Hercule Poirot with your grandma or put your kids in front of some wholesome PBS programming, that’s the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which is also on the chopping block.

Just this year, the NEA made generous contributions toward arts journal Conjunctions; indie publishers like Archipelago, Graywolf, and Coffee House; and to almost every regional symphony orchestra, dance recital, and one or two thousand things I may have left out. The NEH underwrites a massive number of research and conservation grants and awards the National Humanities Medal, given in the last couple years to Larry McMurtry, Jhumpa Lahiri, Annie Dillard, Wynton Marsalis, and Terry Gross.

Below, a reminder of just a few of the many artists and works for which we owe the NEA our gratitude.

John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

The book’s first publisher, the Louisiana State University Press, received a grant of $3,500 from the Arts Endowment, and the book was published in 1980. In the first year alone, the novel sold more than 50,000 copies, winning Toole a posthumous Pulitzer Prize. Today the book has appeared in 18 languages, and there are nearly 2 million copies in print.

Alice Walker, The Color Purple

Walker was one of 41 writers to receive an NEA Discovery Award in Literature in 1970, which she used to complete her debut novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland. Since then, she has published more than 30 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, including The Color Purple, which won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award for Fiction and was adapted into a film that was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actress.

The Complete Works of Charles Mingus

Following the bandleader’s death in 1979, his widow Sue Mingus received an NEA Music Fellowship of $20,000 to catalog Mingus’s vast archives, which were found to include the 500-page score for Epitaph, a symphony for 31 musicians that premiered at Lincoln Center thanks to another NEA grant in the amount of $30,000. The New Yorker wrote that it “represents the first advance in jazz composition since Ellington’s Black, Brown, and Beige, written in 1943.” Contemporary performances by Mingus Big Band, Mingus Orchestra, and Mingus Dynasty are able to keep his legacy alive thanks in large part to the NEA’s support in preserving his output.

Norman Rush, Mating

Rush, via the NEA site: “The NEA grant, coming closely after one from the New York State Council on the Arts, gave me confidence that I might truly be able to devise a viable literary life. We lived modestly, and the material contribution the grant made was significant. It also encouraged me to apply for other grants while I worked on my first novel, Mating, whose positive reception changed everything for me.”

Jane Smiley, Barn Blind

Smiley, via the NEA site: “I received my first NEA fellowship in 1978. I got $7,500, which was a tremendous amount at the time and enabled me to write my first novel, Barn Blind. The pat on the back was worth as much as the money. For the first time I felt rewarded rather than just allowed to proceed. I received my second fellowship in 1987, after I had established myself as a promising young writer. In both instances, money from the NEA smoothed my passage through difficult transitional moments in my career, and helped me move forward.”

Joy Williams, State of Grace

Williams, again via the NEA site: “It’s a remarkable thing to be rewarded by one’s own government for being an artist, for pursuing a unique vision. The recognition and money were enormously helpful to me at the time, and since then I’ve been a judge for the NEA and know that the criterion is excellence, always only excellence and promise. It’s a great fellowship to receive, a sustaining and emboldening award.”

Tobias Wolff, This Boy’s Life

Wolff, via the NEA site: “During the period of my first fellowship I completed a collection of short stories, In the Garden of the North American Martyrs, and during the second I made a substantial beginning on a memoir, This Boy’s Life. The grant allowed me to write without one eye on the wallet and the other on the clock, and to experiment and develop in ways that would otherwise have been very difficult. I will always be profoundly grateful to the NEA for the difference it has made in my life and work.”

And the list goes on. Sherman Alexie’s The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex, Lorrie Moore’s Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?, John Ashberry, Grace Paley, Jamaica Kincaid, Jonathan Franzen, John Berryman, Robert Creeley, Wallace Stegner, William Gaddis, Louise Erdrich, Paul Bowles, Charles Olson, Joyce Carol Oates, and Robert Penn Warren are just a few of the luminaries propped up by funding from the National Endowment of the Arts. A complete list is on their website.

Recent work by J.W. McCormack appears in Conjunctions, the Culture Trip, the New York Times, and the New Republic.