Even longtime residents of New York City are often unfamiliar with the South Street Historic District, a very small section on the east side of downtown Manhattan. Situated below the Brooklyn Bridge, the neighborhood once served as the city’s port, was long home to its wholesale fish market, and later the shopping mall at the South Street Seaport, which has recently gotten a snazzy makeover. Less still is known about the residents who changed the shape of that neighborhood’s course, mostly artists and writers who moved there in the 70s, 80s and 90s because it was one of the last remaining affordable parts of Manhattan. Despite its location at the tip of the island, and next to two of its major bridges, when I was growing up there in the 90s and early aughts, the Seaport felt mostly isolated from the city at large, trapped between industrial and tourist aesthetics; each time my grandmother would visit the loft my family lived in, she would gleefully tell us the cab driver had yet again been uncertain whether he should drop her off alone in front of our building.

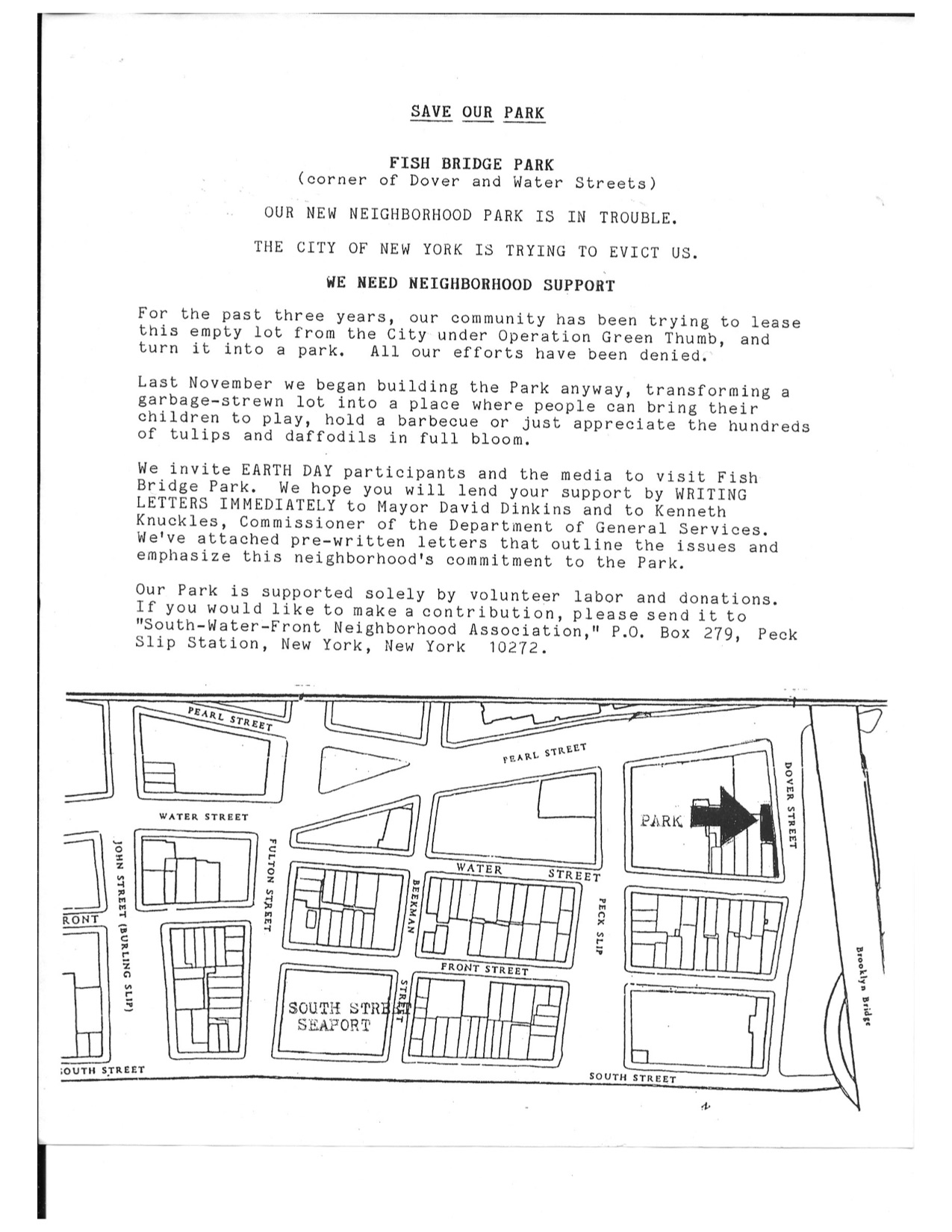

It was in this place, surprising as it may have been, that my mother and our neighbors banded together to transform an abandoned city lot into what would eventually become a community garden, and then a tiny city park. Modern community gardens in New York have their genesis in the 1970s, when the city’s disastrous financial situation left many lots vacant, and residents, particularly in lower-income neighborhoods, began to take over those lots for their own use. In a city of limited space, they are constantly at threat (though, due to the internet, the barrier of entry to understanding how to get one started is much lower than it used to be). FishBridge Park —dubbed that by its makers as an homage to the neighborhood’s fish-mongering legacy and location—is a ripe example of a community project that came together largely because of the forces that are working against many of the communities in the city that would benefit from such a place. The garden was one of my purest childhood pleasures, and its creation one of my earliest memories. So for Earth Day, I spoke to some of the community members involved—including my mother—on what it took to take over a place that had been neglected and was now wanted, what it did for that community, and where both stand now.

Videos by VICE

GENESIS OF THE GARDEN

ANN DERRY, 65, writer, author’s mother: There were a lot of community gardens in New York then, especially on the Lower East Side, big community gardens which have mostly since been built over. Because there was more space then, and there was a whole movement of people squatting in lots on the Lower East Side and turning them into gardens.

In our neighborhood, we had three or four vacant lots that were vacant mainly because buildings had been abandoned and then either there had been fires in them, or the buildings had just collapsed. One of them was the one on Dover Street and Water Street, and it was just the classic weed strewn vacant lot, with all this trash in it, behind a chain link fence. I think it was Gary’s idea to clear it out to make a garden.

GARY FAGIN, 68, conductor, Knickerbocker Chamber Orchestra: The actual property is too small to build a separate building on. And of course the configuration of the property, the reason it is the way it is now, is because when Robert Moses built those ramps from the FDR to the Brooklyn Bridge, Dover Street was actually 10 to 20 feet to the north. Previously, Dover Street was where the ramps are. And so they put the ramps there and they moved Dover Street.

The genesis is a bit clouded in the mists of time, but you remember that parcel, which, when we moved there, it looked like two different parcels; a lower parcel on Dover and Water, and then the upper parcel, which had been taken over by a parking lot, before the Jehovah’s Witnesses built there. The lower parcel was just being used as a rat-infested garbage dump. It was around ’86 when a few of us decided that it seemed to be abandoned. First thing we did was cleaned it up a bit. I remember going in there with a wheelbarrow and heavy gloves and pulling out all sorts of awful crap and garbage.

Then we got the city to come in there somehow and clean it up—I forget how that happened. But as soon as it was cleaned up, there was a guy that had a parking concession under the Brooklyn Bridge ramps, and he started parking cars in there. We were outraged by that. And to make a long story short, we put up a ruckus, and the city came by and basically kicked him out and put up a chain link fence.

DERRY: Gary went to the city, and asked for permission, and they said ‘It’s a city lot, you can’t have it.’ That was in the fall of 1990.

So we said, well, that’s too bad, and cleared out all the trash ourselves and built beds. I don’t know where the money came from, I don’t know where the lumber came from, but we built these beds and we planted tulips. [A Post article from the time claims the money was raised through a neighborhood party.] None of us knew anything about gardening. We planted a bunch of tulip bulbs and daffodil bulbs and I remember planting them and not knowing which end went down. Like I wasn’t even sure we had the right end down and up, because we knew so little.

Then winter came, and spring came, and the tulips and the daffodils started coming up, and we were like, wow, this is so cool. At the same time, right before Earth Day, Gary got a notice saying, ‘You now owe the city $7,000 a month in rent because you’re squatting on this property.’

EARTH DAY, 1991

FAGIN: That’s when things really got noticed by the press.

DERRY: We were like, okay, well, what are we going to do? We’re not going to pay $7,000 a month for this. I’m sure this was my idea: I said, we’ll write a press release, and we’ll send it to all these news organizations, and we’ll tell them what happened. So we wrote this press release, and we faxed it, because that’s what they had then, to the New York Times and the Daily News and the Post and New York 1 and all these different people, on maybe a Friday, before Earth Day weekend. Earth Day was Monday.

FAGIN: Across the street, there was a guy by the name of Chris Oliver who worked for The New York Post. And so Chris wrote an article about us. And his brother Dick Oliver at the time was a TV reporter. So Chris’s article got Dick to come with a TV crew and film us. I remember I got a call at 6:30 in the morning saying ‘We’d like to do a live feed at 7:30 about your garden.’ And I remember getting on the phone and calling everybody I could think of, and probably your mom, telling them, ‘Wake up your kids, and bring them down.’ [laughs] Because ‘kids and garden,’ how can you lose with that?

DERRY: I got this phone call Monday morning at like 6 AM, and Gary’s like, ‘You gotta get over here, there’s all these cameras, and all these people here.’ It was a slow news day—hard to believe in this day and age. We called all the people in the neighborhood, and everyone showed up with their kids, and the tulips were blooming! It was a perfect Earth Day story. We were all over the place with these little kids and this community garden with the little tulips.

FAGIN: Of course, what happened was all the other networks saw it, and they started sending crews down all afternoon. So we were on the afternoon show and then we were on the evening show and they would interview us and they would call the city, and the guy there was like, ‘Why am I getting all these calls from TV stations as to why we’re kicking these kids out of the garden, this unused vacant city lot?’

DERRY: The mayor’s office is like, well, this doesn’t look good for us. [laughs]

FAGIN: That next day we got a meeting at City Hall and that was the beginning of us getting the parcel, which turned out to be more than just the lower parcel, it turned out to be that whole sliver all the way to Pearl Street. Then we got a temporary lease, then we got put into the GreenThumb program, and then the GreenThumb program got put into the Parks Department, and we were one of the first two GreenThumb gardens to be issued permanent park status. When you’re a GreenThumb park you’re always susceptible to being taken over by anybody, a developer, or whoever buys the property. But once you’re a real park, you’re city park land and that never goes away.

GARDENING AND KEEPING THINGS ALIVE

DERRY: GreenThumb is an organization that helps facilitate all these community gardens all over the city; you get like a year lease or a two year lease, and they have this incredible support. You can go and get dirt and bulbs and more lumber to build things and seeds and tools. It’s mainly designed not for an upper-middle class community in the Seaport, but for people who are lower-income communities who are actually growing vegetables. You would go to these meetings every year, and everyone would talk about their issues and their problems and what they were trying to figure out. And they were teaching all these communities how to garden. The people who worked there were lovely and wonderful.

We built compost bins, we composted all of our scraps. We used to go to the police stables—I’m sure you remember this—on Varick Street and got horse manure to put in the compost [laughs]. It was so much fun. We’d drive over there in Gary’s car with the plastic garbage bags and shovel all this horse manure and straw into them, and then dump them into the compost bin. It was great compost.

A lot of people learned to garden there. I learned everything I know about gardening there. One year we went to the Seaport at Christmas time; they had all these living Christmas trees outside and—after they were done with [them]—we hauled home seven of them back to the parking lot and planted them all the way along the edge. We didn’t know what we were doing. Of course most of them died, but two of them are still alive, and huge, by now. Of course we never thought about how big a tree that would be. Everything was on raised beds above the ground, because it’s Manhattan. But the trees we actually dug into the ground and it was a collapsed building underneath, so you’d be digging out bricks and old nails. These trees grew underneath that. It was amazing actually. It was kind of magic.

BECOMING A CITY PARK

FAGIN: I think we were one of the first in the pipeline, I believe, to apply for transference into the City Parks Department. And I think for two reasons, or maybe three reasons. Number one: We were the closest park to the municipal building. And so when people came to the office of GreenThumb and GreenThumb wanted to show them a GreenThumb park, I’d often get a call and they’d say, ‘Hey, we have some people from out of town, and we want to come over and show people the garden,’ and they would be able to walk right over in less than five minutes. So number one, that was convenient. Number two, I think just being in lower Manhattan, being in such a historic area, was to our advantage. And number three, we played our politics very, very well. When we had our tenth anniversary, in 2001, we got the parks commissioner down there and we had very good pipelines to the highest levels of the parks department. And we were constantly on their radar. And it was a no-brainer really, because I think the main consideration was that that land was never going to be sold to anybody. It wasn’t a developable piece of property. So there wasn’t any pressure from anybody else that you’d put all this time into the garden just to have it destroyed and have affordable housing built on it. That was never going to happen on this property.

The thing is, you’re defending yourself not against rapacious developers; for the most part, you’re defending yourself against another good thing, which is affordable housing. Or senior housing, or something like that. So your argument for the worth of your open space is diluted somewhat in comparison.

THE FUTURE

ZETTE EMMONS, 73, retired, formerly of the Newark Museum: We get money from the GreenThumb grant every year. The office is right around the corner on Gold Street, so I go to the meetings, but I’m just about the only one from Manhattan who goes. All the other people who come, almost none of them are from Manhattan, unless they’re from way uptown.

This neighborhood is, as you know, a little different than most of the neighborhoods that have neighborhood gardens. Our park is tiny compared to the other ones. They give us all this equipment, like wheelbarrows, and we could get a Port-A-San for the summer, and I say, I don’t think we need that. [laughs] People can go over to Cowgirl Seahorse if they need a restroom. But people do really love it.

It’s looking really good. We took out all the kids stuff, except for a little kids’ table. But here’s the problem, is the people who moved into the neighborhood are so busy and working all the time. Sometimes people think they’re going to do it all the time and then they don’t. We just need younger blood, basically. Because if it’s going to be run by a bunch of 70-year-olds, that’s ridiculous. We can’t shovel snow.

FAGIN: Zette and I have, for the last over five years now, been trying to hand over the reins to a new generation of people. We were all in our thirties, some people in their twenties, when this all went down. And of course we could afford to live there because we all moved down there and the rents were cheap and people were able to buy in and have an affordable place. That paradigm is long gone. And also, the people who would do that at the time had a certain kind of sensibility. The twenty- or thirty-somethings who are in our neighborhood now do not share the kind of sensibilities that we had. First of all, they’re not artists or architects or photographers or musicians or dancers or theater people. They’re more finance people, they’re tech people, that sort of thing. And so the interest in doing the kind of pro-bono community advocacy that we had when we were younger is just not there. Zette and I have simply not been successful in finding people to, number one, participate in the garden and the dog run, and number two, take over the reins, take over responsibility for it.

We had a conversation with the GreenThumb rep about that. He said this is sort of endemic in the second decade going into the third decade of the 21st century, that the people that really began the grassroots work that ended up creating community gardens and the entire GreenThumb program in the last couple decades of the 20th century, and it’s really hard, all over the city, for those people to find people to fill their boots. Because neighborhoods have changed, sometimes as a direct result of the improvement to the neighborhood of the community garden!

DERRY: That was a very strong, small community. We had block parties on that block, and everyone would come. It was one of those things that everyone who had a lot of little kids the same age, and people who didn’t were all artists, they all knew each other. The community immediately saw that that was a place to gather. Because there was nothing down there to do that in. It wasn’t like we were hanging out at the Seaport. And it really made a total difference in the neighborhood—how it felt to walk down that block and have that garden there. It was amazing to go from a vacant lot to a garden in like a year.

Follow Kate Dries on Twitter.

VICE is committed to ongoing coverage of the global climate crisis. Read all of our Earth Day 2020 coverage here, and more of our climate change coverage here .