Colette was one of the most prolific and venerated female writers in France, publishing more than 30 novels and novellas over the course of her career during the fin de siècle. Her works were intimate and deeply introspective—many of them semi-autobiographical, like her breakout The Vagabond, which traced her music hall experiences. She also became an internationally renowned figure and feminist icon, known for her complete independence and high visibility queer relationships at a time when it was illegal for women to even wear trousers.

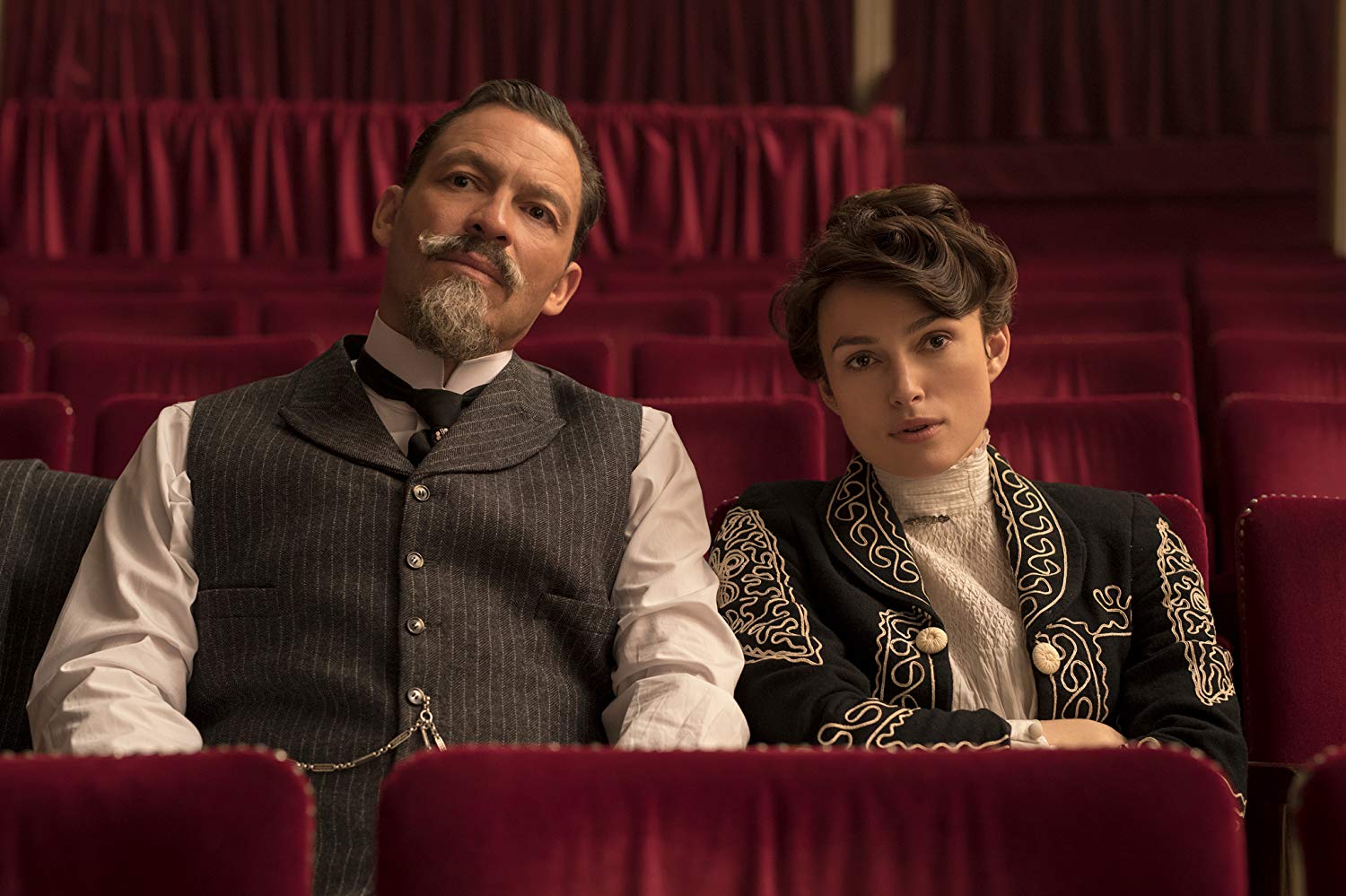

But at the start of Colette’s literary career no one knew her name. Her husband, Willy, took the credit for Colette’s Claudine novels, even as they became an international sensation. Colette, the film—starring Keira Knightley and Dominic West, and directed by Wash Westmoreland—recounts the story of Colette’s rise to literary success and the coercive marriage that stole her byline.

Videos by VICE

Below is an exclusive clip of one of the film’s most tenuous scenes—in which Colette begins to realize that her work ought to be hers, and that her husband is dangerously manipulative. I also spoke to director Wash Westmoreland about Colette’s work, and the process of making the film.

VICE: What led you to Colette?

Wash Westmoreland: It’s Richard, my partner. He was an avid reader, and when he started on Colette—I’ve never seen him fall into a book like that, and that guy can fall into a book. We’d be in the house, and he’d be like, “oh my god” and “oh my god.” My curiosity was piqued, and I started reading Colette too. We were very much of one mind that this would make a great film. Colette’s life is a natural narrative for a four or five season TV show. But for a two hour film, Colette’s marriage to Willy is a natural narrative about a woman that was struggling to have her voice heard, and a man controlling it. He eventually feels threatened by that, and does everything he can do to keep her down. It’s the core dynamic that runs through the story, and it can be told a thousand a ways.

It’s been compared to Big Eyes, but I don’t care. It’s happened a thousand times today already—in the workplace, a woman dealing with a male superior saying the same thing five minutes later and claiming credit for it. All of the instances like that. I feel like that’s why Colette’s story resonates, it’s about a woman struggling to get out.

What research went into this film?

Reading a lot of Colette’s novels and biographies. We stayed in Paris and visited all of the places the Belle Époque had made famous, and then we traveled to her village in Burgundy and saw her family home—the museum. We did all of them, and periodically thought, “Oh that would be neat, that could go in the film.” I didn’t know it would be 16 years until that came to fruition.

That’s quite an amount of time to pass! Why did it take 16 years to make the film?

The place we were in our careers. Colette is quite an elaborate production and you have to have a certain momentum. There was also, I feel the script needed time to distill from a million details of Colette’s life, into what would be on screen. Choosing the story. In that time we went through about 20 drafts.

When we first started writing Colette, Keira Knightley was also not an option. After [our film] Still Alice, when [that] film reached its peak, we were able to cast her. She needs to go from 19 to 34, which she does beautifully in the film—the way she grows on screen is just incredible. I think she’s a brilliant actress. She has a special ability to convey things with an emotional translucency where you truly understand what is happening to her. Colette begins the story very much at the whim of her husband, and we needed to have a strong character capable of becoming what she becomes at the end—and the start of The Vagabond.

Colette was such a subversive, queer, feminist icon—do you also feel there’s a sense that audiences wouldn’t have been ready for this film until 2018?

When we first finished the screenplay, we thought, “Oh this will happen straight away, it’s such a great film.” We’d pitch the film, “and then she becomes part of the lesbian underground, plays with masculinity, and is a forerunner of what might be considered today’s butch-lesbian community. And Missy is a forerunner of transgender identity.” And people would just be staring at me. But now, of course, that conversation has come very much into the public eye. So much progress has been made with trans visibility.

There are trans actors in the movie, though many of the characters are historically cisgendered—and it works perfectly well. We’ve cast lesbian actresses, and recast historically white characters to be played by Asian British actors and black actors as well. It’s time that period pieces were more inclusive. It shows that society is more complex and that there’s a way to tell the period story that’s not starched white—white people, white hegemony. That there’s a way to tell these stories with an inclusive, diverse cast. Just invite everyone into that process, that’s what today is about.

In Colette, it’s the hand that holds the pen that writes history. And the hands that held the pen were always the hands of a white man. That’s how history has been defined—and in re-exploring history I think it’s important to note other voices who didn’t have the same access to creating narratives. It’s interesting that when Colette champions that phrase on Willy, she’s the one who holds the pen. She’s the one, now, who’s able to give a different perspective on the world through being able to write and being able to be published.

It’s the same issue with women in film today. The predominance of men directing in Hollywood, the idea that women don’t make films that aren’t as commercial—it’s exactly the same. In the 19th century so many women writers had male pseudonyms like George Eliot. Writing, putting things to paper, is almost like going into people’s minds, and the female point of view was so threatening to men who control of the literary and art scene. That was a barrier that had to be broken through, by Colette, by great women writers who have come since.

How much is the film Colette true to history?

All of the major events in the film are true. This is especially true of the events in Colette’s relationship and marriage. What we have done in adapting it, is we’ve refreshed the timeline in certain ways, and we’ve tightened of the story to foreground her development. That became the defining principle and the core narrative—Colette finding her voice as an artist through this oppressive marriage. The historical details were essentially around that core principle of that story.

If you sat down with an expert, someone who knows everything there is to know about Colette—there are various artistic licenses taken all the way through. But we tried to pay tribute to Colette’s own way of writing, which was to take her advice that she’d gotten from Willy and kind of create narrative out of it. I feel like it was something that was resonant with Colette’s working method, with the way this film was written.

It’s interesting—in the initial phases when Willy is looking at the text he’s in charge, he’s the one making the edits. But further on you see that she has now got more control of the narrative. He asks her to change things, and she says “no, I won’t.” It’s because he’s a thinly disguised character within the Claudine novels. She now controls him, and at one point even threatens to kills his character off. He’s intimidated by the growing power and the creative force in her marriage.

What are your favorite Colette novels?

I think my favorite is just her highest style of literature, it’s Chéri and The Last of Chéri. They’re beautifully written works, incredibly insightful, into the dark mind and the human heart. During the period of her story, The Vagabond, I think stands out.

That one is also my favorite, of her semi-autobiographical works.

Colette had dropped out of bourgeois society—she was not doing high Shakespeare and theatre. She was doing music hall with the show girls and the Russian acrobats and the dog trainers. She was touring, she was staying in these cold hotel rooms and earning her own money, and having the kind of freedom to be a woman of her own, living independently. And she expresses that in The Vagabond in such an interesting way.

So many stories, like The Vagabond, actually came from Colette’s real music hall experience. And that was when she was recognized as a great writer, nominated for the The Prix Goncourt. Probably would have won if it wasn’t all male judges. She was a force to reckon with. It’s amazing to read her novel in one hand and her biography in another hand, because so much of what happens in her novels comes out of her real life experience. I think so many novelists are like, “She’s a great writer, but what’s her secret, hidden life.” Whereas with Colette, it’s all out there in the public space. I mean, she was dancing on the stage naked at a time when women would be debating about whether or not to show an ankle in public.

She set such a wonderful example—if you’re stuck behind a barrier, be inspired by Colette, and think about how you can get through it.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Nicole Clark on Twitter.