Listen to “Chapo: Kingpin on Trial” for free, exclusively on Spotify.

This story has been updated to include comments from El Chapo’s defense attorneys.

Videos by VICE

For the first time since the trial of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán ended on Feb. 12, a member of the jury has described what it was like be part of the historic case.

In an exclusive interview with VICE News, the juror claimed that at least five fellow jurors violated the judge’s orders by following the case in the media during the trial. The juror also shared details of the deliberations, the extraordinary security precautions that were in place, and the jury’s views on Chapo, his lawyers, the prosecution, and several key witnesses.

The juror requested anonymity “for obvious reasons” and declined to provide a real name, noting that the jurors didn’t even share their identities with one another. They did form friendships, though, and referred to one another by their numbers or used nicknames based on tastes and personalities. The cast included Crash, Pookie, Doc, Mountain Dew, Hennessy, Starbucks, Aruba, TJ, 666, FeFe, and Loco.

“We were saying how we should have our own reality TV show, like ‘The Jurors on MTV’ or something like that,” the juror said.

The juror reached out to VICE News via email a day after the guilty verdict came down, and we spoke for nearly two hours on a video chat the following day. The 12 jurors and six alternates were anonymous under orders from the judge, and cameras were strictly forbidden inside the courtroom. But they sat in open court for all 44 days of the trial, their faces plainly visible to Chapo and anyone from the press or public who chose to attend.

“You know how we were told we can’t look at the media during the trial? Well, we did.”

I was a regular at the trial, and I recognized the juror from my time in the courtroom. The juror shared detailed notes taken during the trial, which were kept against the instructions of the court. Information from the jury selection process provided further corroboration about the juror’s role in the case.

The jury deliberations dragged on for six days largely because of one stubborn holdout, the juror claimed. The juror said another factor before the deliberations began was the prospect that Chapo would be forced to spend the rest of his life alone in a prison cell.

“A lot of people were having difficulty thinking about him being in solitary confinement, because, well, you know, we’re all human beings, people make mistakes, et cetera,” the juror said. A handful “talked about whether or not he was going to be in solitary confinement for the rest of his life, because if he was, they wouldn’t feel comfortable finding him guilty.”

Now that Chapo has been convicted, he’ll likely be sent to the so-called “Alcatraz of the Rockies,” a federal “supermax” prison in Colorado where many high-profile inmates are kept in solitary.

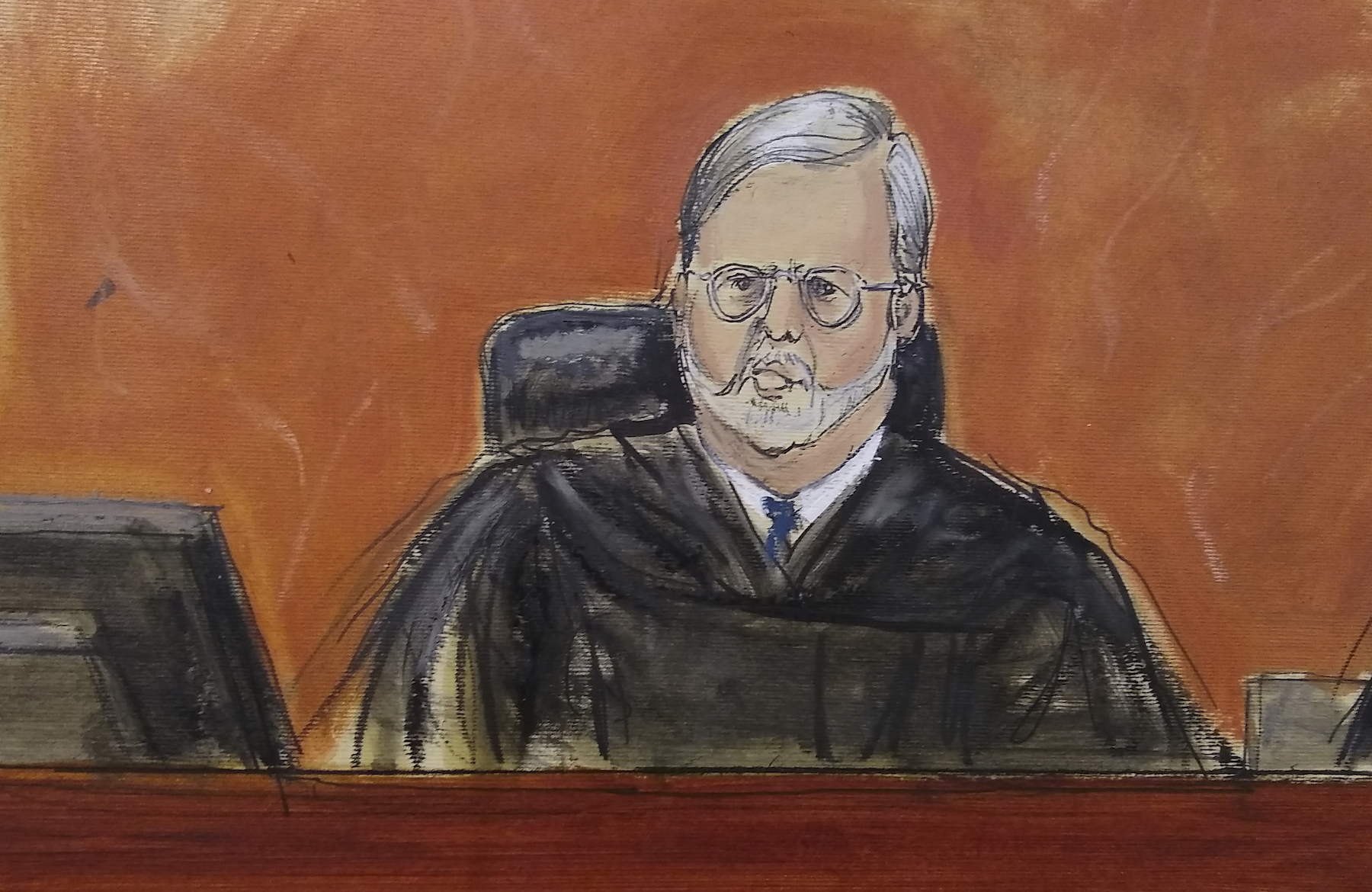

Judge Brian Cogan routinely admonished the jurors to avoid news coverage and social media, and to refrain from discussing the case with each other, so that the verdict could be decided only on evidence from the courtroom. Those rules were routinely broken, according to the juror: “You know how we were told we can’t look at the media during the trial? Well, we did. Jurors did.”

Part of my coverage of the trial included sharing news, analysis, and observations from the courtroom on Twitter. The juror said they routinely checked my personal Twitter feed and tweets from other journalists. “We would constantly go to your media, your Twitter… I personally and some other jurors that I knew,” the juror said.

The juror reached out to another juror at the request of VICE News but said nobody else wanted to speak on the record. VICE News agreed to withhold personal details at the juror’s request. To further protect the juror’s identity, gender-neutral “they” pronouns are used throughout this story, and VICE News is not disclosing whether the juror was an alternate or one of the 12 people involved in deliberations.

Judge Cogan informed the jurors after the verdict was handed down that they are allowed to speak to the media, though he cautioned them against it. No other jurors have spoken out publicly, and because they are anonymous and not reachable for comment, parts of this juror’s account could not be independently verified.

If multiple jurors were indeed reading about the case in the media, Chapo’s defense team could seek a new trial.

“Obviously we’re deeply concerned that the jury may have utterly ignored the judge’s daily admonitions against reviewing the unprecedented press in the case,” said defense attorney Jeffrey Lichtman, who also noted concern that jurors may have seen “prejudicial, uncorroborated and inadmissible allegations” about Chapo during the trial. “Above all, Joaquin Guzman deserved a fair trial.”

Eduardo Balarezo, another attorney who represented Chapo during the trial, called the juror’s comments to VICE News “deeply concerning and distressing.”

“The juror’s allegations of the jury’s repeated and widespread disregard and contempt for the Court’s instructions, if true, make it clear that Joaquín did not get a fair trial,” Balarezo said in a statement. “The information apparently accessed by the jury is highly prejudicial, uncorroborated and inadmissible — all reasons why the Court repeatedly warned the jury against using social media and the internet to investigate the case.”

Balarezo added that the defense team “will review all available options before deciding on a course of action.”

A spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s office in Brooklyn declined to comment.

The juror’s recollection of testimony and details from the case suggested they had paid close attention and carefully considered the evidence. They said speaking out after convicting the world’s most notorious drug kingpin wasn’t easy. At one point in the interview, I mentioned it was brave to come forward after serving on Chapo’s jury.

“I’m either brave or stupid,” the juror responded. “It could go either way.”

The verdict

Some jurors were reportedly indifferent, while others were willing to consider an acquittal.

“There were jurors already with their minds made up,” the juror said. “There were jurors that still weren’t sure, and there were jurors that were looking to find possible ways, possible discrepancies to find him innocent.”

Prosecutors called 56 witnesses to testify against El Chapo, including 14 cooperators — among them his mistress and high-ranking cartel members — who testified in exchange for reduced sentences and government protection. The defense called just one FBI agent, who testified for 30 minutes. Still, it took six days of deliberations to reach the verdict.

“There were jurors already with their minds made up.”

The juror said one woman was the holdout: “She would say ‘yes,’ then she would come home and the next day she’d say, ‘You know what: I thought about it and I changed my mind,’” which forced the jury to restart deliberations on certain charges.

While the 12 jurors deliberated, the six alternates were stuck in a small room, where they passed the time playing poker with Monopoly money and watching movies on a court-issued laptop.

The juror claimed two people essentially refused to participate in the entire process: “They said that basically, ‘I’m here, I don’t care what you decide, guilty or not guilty. I disagree with whatever you want to do. I’m not going to participate because I’ve been in so many juries that at this point I don’t care.’”

But eventually, the jury unanimously found Chapo guilty on all 10 counts of his indictment.

After the guilty verdict was handed down, the juror recalled, “We were all pretty sad, in a way.” The juror was nervous and fighting back tears, and said at least four people wept.

The juror said the emotions weren’t out of fear or relief; they felt bad about sending Chapo away for life: “People probably think, ‘Aren’t you happy you convicted this guy for all these things that he had done?’”

The juror said they were overwhelmed about the magnitude of the decision to convict.

“Before I even entered the room to read the verdict, I was about to have a panic attack,” the juror said. “I was really nervous. I was shaking.”

Extreme security

Chapo’s trial was in the Eastern District of New York, and to find jurors the court mailed a 31-page questionnaire to roughly 1,000 people across Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and Long Island. Many respondents were eliminated because they claimed knowledge of the case or feared for their personal safety.

The juror who spoke with VICE News said they were being honest about not knowing much about Chapo beyond his alleged status as a Mexican drug lord. They realized the trial was going to go on for months and be dangerous enough to require anonymity and an armed escort to and from the courthouse.

The allure was being part of history: “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing. This is the case of the century. Do I want to live it… or do I want to watch it on the screen?”

The jury was a diverse group that included four native Spanish speakers, several African-Americans, and a roughly even mix of younger and older people. But they were random New Yorkers who were thrown together for hours in a cramped room.

The juror described an instance where two people had to be separated by a U.S. Marshal when an intense argument broke out over personal space in the jury room.

Cell phones were confiscated, and the judge had warned them not to discuss the case. With everyone paranoid about the prospect of being threatened or killed by the Sinaloa cartel, the topics of conversation were initially limited to the Knicks and the weather.

“No one wanted to talk about their personal life,” the juror said. “We didn’t want to give out what we did for a living.”

The jurors were allowed to return home every night, and they were escorted to and from the courthouse each day in groups of five in vans driven by U.S. Marshals, and the juror described scanning their surroundings and being nervous until they entered the vehicle.

“It was pretty weird,” the juror said. “We had to meet up in a secret location.”

A spokesperson for the U.S. Marshals Service declined to discuss “specific security measures” that were in place for the jurors.

The juror said some conversations happened on the ride home. Other times they would whisper to each other or mouth words. In some instances they would write notes on paper in the courtroom. The topics ranged from guesses about the identity of the next cooperating witness to the latest media coverage: “The judge said, ‘You can’t talk about the case among each other,’ but we broke that rule a bunch of times.”

Media exposure

Reporters were not allowed to have recorders, phones, or laptops inside the trial, but we were allowed to have electronics inside the building, and it was common to share updates on Twitter about developments that occurred without the jury present.

The juror said several people followed this coverage, which included reporting on evidence that Judge Cogan ordered withheld from the jury at the request of the defense and prosecution. Court documents unsealed at the request of VICE News and the New York Times on the eve of jury deliberations contained allegations from a witness who claimed Chapo had drugged and raped girls as young as 13.

El Chapo’s lawyers denied the allegations, saying they “lack any corroboration and were deemed too prejudicial and unreliable to be admitted at trial.”

I mentioned on Twitter that the judge was likely going to meet with the jurors in private and ask whether they had seen the story. The juror said they read my tweet before arriving at the courthouse and reported what was coming to other jurors: “I had told them if you saw what happened in the news, just make sure that the judge is coming in and he’s gonna ask us, so keep a straight face. So he did indeed come to our room and ask us if we knew, and we all denied it, obviously.”

The juror who spoke with VICE News said that “for sure” five jurors who were involved in the deliberations, plus two of the alternates, had at least heard about the child rape allegations against El Chapo. The juror said it didn’t seem to factor into the verdict.

“We did talk about it. Jurors were like, you know, ‘If it was true, it was obviously disgusting, you know, totally wrong. But if it’s not true, whatever, it’s not true,’” the juror recalled. “That didn’t change nobody’s mind for sure. We weren’t really hung up on that. It was just like a five-minute talk and that’s it, no more talking about that.”

Asked why they didn’t fess up to the judge when asked about being exposed to media coverage, the juror said they were worried about the repercussions. The punishment likely would have been a dismissal from the jury, but they feared something more serious.

“I thought we would get arrested,” the juror said. “I thought they were going to hold me in contempt.… I didn’t want to say anything or rat out my fellow jurors. I didn’t want to be that person. I just kept it to myself, and I just kept on looking at your Twitter feed.”

The juror said at least seven people on the jury were aware of a story published Jan. 12 by the New York Post about an alleged affair between Lichtman and one of his clients. At the request of the lawyers, Judge Cogan met privately with the jury to ask a vague question about whether anyone had been exposed to any recent media coverage. The juror said the group responded honestly: They hadn’t seen anything. But moments after the judge left, someone allegedly used a smartwatch to find the article.

The juror said several people had already been put off by Lichtman’s style of questioning during the trial: “They thought he was mean and he was nasty because of the way he would talk to the witnesses, and you know, I always told them he’s doing his job. That’s his job.”

The case

The juror said many people were skeptical of the cooperators who cut deals with the government and flipped on Chapo, pointing to several instances where they appeared to contradict themselves or each other.

Read more: The 10 wildest moments and stories from Chapo’s trial.

Juan Carlos Ramirez Abadia, a Colombian drug lord known as Chupeta, or Lollipop, with a ghoulish face from multiple plastic surgeries, made an especially strong impression. The juror jotted down a note: “Scary-looking dude.”

“I’ll never forget when I saw Chupeta’s face as soon as I entered the courtroom,” the juror recalled. “He literally made me jump.”

The juror said their peers were appalled that prosecutors were working with the likes of Chupeta, who took responsibility for 150 murders, including several in New York. Same with Christian Rodriguez, a Colombian systems engineer who worked for the cartel but helped the FBI eavesdrop on Chapo in exchange for immunity and cash payments.

The jurors shared a laugh over testimony by witness Pedro Flores, who along with his twin brother was one of Chapo’s main drug distributors in the U.S. Flores admitted on the witness stand that while he was in DEA custody, he snuck into the bathroom during a visit with his wife and got her pregnant: “We were all just crying hysterically back in the room. That was one of the most hilarious things.”

The juror said they also had fun with nicknames for the prosecutors. Adam Fels was “either Mr. President or Politician because he looks like the type of guy to run for office or be a politician.” Michael Robotti was “Tall Guy.” Andrea Goldbarg was “Glasses.” Amanda Liskamm was “Pearls.” Anthony Nardozzi was “Frat Guy.” And the straight-laced Gina Parlovecchio was “Vicki.”

“One of the jurors was like, ‘She looks like a Vicki,’” the juror said. “And we’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, she does look like a Vicki.’ So that’s it, it was no more Gina, just Vicki.”

The defense attorneys were just “two bald guys and Lichtman.”

Ultimately, the juror said, there wasn’t much Chapo’s defense could do. Even if the jury didn’t believe the cooperators, the government showed several videos, dozens of wiretapped phone calls, and hundreds of intercepted text messages. It was plenty to convince 12 people to find Chapo guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Now that the trial is over, the juror has returned to a normal life and job. They are still worried about safety and plan to keep their role in the Chapo case secret from friends, colleagues, and extended family members, at least for the time being.

In the end, the juror left feeling that Chapo was definitely guilty as charged but also a product of his environment: “I think he was just living a life that he only knew how to live since he was young, so it was something normal to him, and not normal to the rest of us.”