Caitlyn Jenner couldn’t remember the name of the movie.

“With Billy Crystal and Curly… God, what was the name of that? He was on a, a cattle drive. Billy Crystal from New York. I used to remember this movie. Billy Crystal was from New York and had to get out and find himself”—and then it came to her.

Videos by VICE

“City Slickers.”

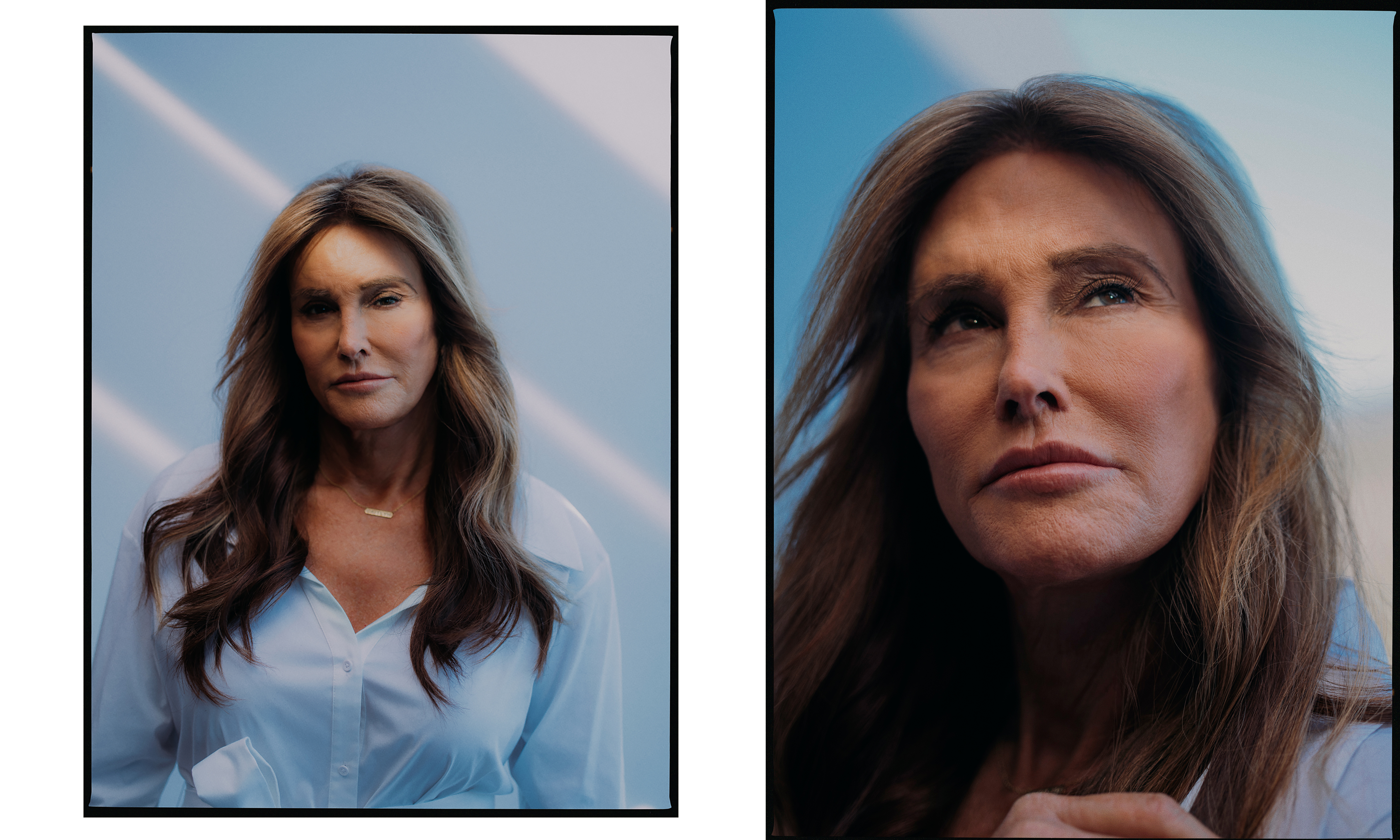

Caitlyn nodded, looking over at me on the sofa. It was a warm fall day in Malibu, California, and the late-afternoon sun split our faces into stark patterns of broken light and shadow. I had flown across the country to spend the weekend with Caitlyn, hoping to get to know the person behind the spectacle of celebrity. Caitlyn was telling me what she wants most for her children, and that’s how we got on the subject of City Slickers.

“They’re sitting around a fire. Billy Crystal says to the wise cowboy, ‘What’s the secret in life?’ The wise cowboy leans over and goes, ‘One thing,’ and then goes on with the conversation,” Caitlyn explained. “Finally, Billy Crystal goes back and goes, ‘What’s the one thing?’ And he goes, ‘That’s for you to find out.’

“I love—to me, that’s life. That one thing in life when you wake up in the morning and you’re excited about the day, you can’t wait for the day to get started—your passion in life.” That’s what she wants for all her children. “If you wake up in the morning you are excited about the day and you have something to do, that is good. And it’s very difficult to find. I want my kids to find that one thing in their life.”

She paused and closed her eyes, as if thinking back to the beginning of her own life, when she was a young person caught in the tidal forces of self and society.

“It’s so difficult for people to recognize the difference between your passion and your popularity. People have a tendency to do things for other people.”

For more than 60 years, Caitlyn lived according to other people’s expectations. As Bruce Jenner, she became an Olympic hero and a charismatic icon of American masculinity, which she then parlayed into a business of endorsement deals, sportscasting gigs, public speaking engagements, and more. At the turn of the century she became the patriarch of the Kardashian-Jenner clan. Though she relished her role as a father, she also felt subservient to her wife, Kris, and was alienated from her own identity as a woman. Then, in 2015, Bruce Jenner came out as transgender and transformed conversations about gender and identity in this country and around the world.

Today, Caitlyn says she is focused on improving the lives of the transgender community, using her platform to bring understanding and awareness. Her charity, the Caitlyn Jenner Foundation, offers grants for organizations that provide services like healthcare, suicide prevention, and housing to transgender people in the Los Angeles area. (I am friends with Zackary Drucker, who is a member of the CJF board and who introduced me to Caitlyn.)

But her relationship with the transgender community has been contentious. Critics claim Caitlyn is a self-interested outsider whose political conservatism and privileged status as a wealthy, white American compromise her involvement in the transgender movement’s intersectional fight for social justice. She voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election, and though she has since denounced his administration’s record on LGBTQ issues, her continued support of the Republican Party remains controversial.

As a trans woman and a journalist, I have always found the wholesale rejection of Caitlyn Jenner to be short-sighted. When Caitlyn came out, she was perfectly situated at the top of America’s most worshiped pop-culture family, which gave her a portal into the mainstream media that no one else could access in quite the same way. The fact that she is a legend in sports history only amplified her significance to me: one of our greatest national icons of male identity was revealed to be a hoax by a transgender woman. By coming out and transitioning before our country’s largest media outlets, Caitlyn unveiled a national identity crisis that will continue to disrupt classical gender narratives in the US for years to come.

I have watched from the sidelines as so many people have torn her apart for perceived failures. While I often agree with the criticism, I also believe Caitlyn is an important potential ally—even though I’m not Republican, it seems useful to have someone like her in that party—and have become disturbed by the demand for ideological purity that can overcome those on either side of the political aisle. Is it possible to find value in someone you perceive to be a part of the problem?

When I arrived at Caitlyn’s monastic concrete compound in Malibu last October, she was in the midst of another controversy, this one over an award she was supposed to receive on behalf of her foundation from St. John’s Well Child & Family Center, a major provider of healthcare services to transgender people in and around Los Angeles. St. John’s decision was met with backlash. More than 2,000 people signed a Change.org petition that demanded, “Stop Dishonoring the LGBTQ Community By Honoring Caitlyn Jenner!!!” By the time my plane landed at LAX, Caitlyn had announced she would not accept the award after all.

For Caitlyn, the experience was simply painful. “It hurts,” she told me in her backyard our first night together. “I’m a human, a person.” It was getting late, but the sun still cast a dim glow over the dusty Malibu cliffs, calmly reflected in the pool. She published a memoir last spring, The Secrets of My Life (“At first it was The Secret of My Life and I go, ‘No, we gotta put a plural’… It’s a lot more than one, my whole life was a bunch of secrets”). She describes the process of putting her life story down on paper as a great unburdening, a final step she needed to take in order to freely inhabit her new world. But what she sees as honesty, the Kardashians decried on their show as a betrayal. It had been a difficult year.

“I got the trans community out there bashing on me, I got the Kardashians out there bashing on me,” she would later tell me. “All I do is sit here in the house and try to stay out of trouble.”

As the sky continued to darken, Caitlyn locked her eyes on mine, as if searching for a sign that I might be the person to really hear her. “ They don’t know me,” she said. It may sound cliché, but she is right. The public met Caitlyn Jenner three years ago. There is only one person who has known Caitlyn all of her life.

Bruce Jenner became an American hero during the 1976 Olympics, carrying an American flag around the track after defeating his title-holding Soviet competitor for the gold medal in the decathlon. But though the Olympian was the picture of masculinity, he had been contrived from the mind of a woman as a mechanism of survival. “I created this image knowingly,” Caitlyn assured me. “I knew what I was doing.”

At the time, the transgender world was still a subculture’s subculture, spoken of quietly or not at all. Though the public transition of Christine Jorgensen in the early 1950s drew attention to the issue, it would take decades for there to be any meaningful change in the public perception of transgender Americans. Throughout the mid 20th century, headlines in American newspapers castigated trans subjects for their immoral gender charades and so-called fraudulent lifestyles.

Growing up in the suburbs of New York and Connecticut in the 1950s and 60s, Caitlyn didn’t have a decent name for what she was going through—the discomfort she felt in her own body, her compulsion to wear women’s clothes. The idea of becoming a woman was unthinkable. And so Caitlyn was alone with her secret. She did what she had to do to protect it, to have a good life.

Caitlyn was a poor student and struggled with dyslexia, but she excelled on the athletic field, finding a home in sports like football before taking up the decathlon in college. Training gave her a reason to keep going every day in an otherwise aimless existence. Her dedication became obsession as she buried her desire to live as a woman deeper and deeper under raw muscle. By 1972, only two years after her first decathlon, Caitlyn qualified for the Munich Olympics, where she finished tenth. Four years later, she became the “world’s greatest athlete.”

But as America roared congratulations for Bruce, Caitlyn was in horror. What have I done? she recalls thinking at the time. The labor of creating Bruce had given her a sense of purpose, but now the distraction had run its course, and she realized that she was stuck with the male character she had created. In the years to come, Caitlyn would benefit materially as Bruce—after the Olympics came advertising deals, television jobs, speaking engagements, and more—but playing that role in American society came at a great spiritual sacrifice.

“Not being able to be yourself?” Caitlyn sighed. “That’s tough on your soul.”

By the early 1980s, Caitlyn was morbidly depressed. She had been through two failed marriages, with four children. She moved to a small home in Malibu and spent years living alone. The anguish of gender dysphoria was overwhelming, and it was becoming more difficult to live as a man. So Caitlyn secretly began to transition: She had surgery on her nose, underwent painful electrolysis to remove her beard, and started cross-sex hormone therapy.

Caitlyn told herself that she would complete transition before she turned 40, in 1989. “I got to thirty-nine, couldn’t do it,” she said. She was still governed by fear, certain that living as a woman would mean losing everything else in life that mattered. Still, four and a half years of hormone therapy had altered her body. She had breasts when she first met Kris Kardashian, Caitlyn told me. “A little B-cup.” She had fallen in love and knew that Bruce could build a future with Kris and her four young children.

“Kris and I got married and I kind of hid it the best that I could,” Caitlyn said. Together, they rebuilt Bruce Jenner into an inspirational speaker who toured the world throughout the 90s, building off his Olympic celebrity. In 1995, they had their first daughter together.

“When Kendall was born, I had liposuction and got rid of [my breasts],” Caitlyn told me. “Because I thought, I can’t even go swimming with my kid.” She says Kris booked the appointment. (On Keeping Up With The Kardashians, Kris has refuted Caitlyn’s claims that she knew her husband was transgender when they met.) I asked Caitlyn if having breasts had eased her emotional distress. “Absolutely,” she said without hesitation. “I cried. But I also had made the decision; it wasn’t time. I still had kids to raise.”

Then, in 2007, the Kardashian-Jenner family created the reality TV show that they are known for today. On Keeping Up With The Kardashians, Caitlyn was an abstract patriarch in a feminine family. Though often the butt of jokes, excluded from family conversations, and generally regarded as secondary to the women in Keeping Up, she still fulfilled an important role in the family. Cameras were there when Caitlyn talked to Kendall and Kylie about the birds and the bees; as she carpooled them to and from school every day; when she walked Khloé, then Kim, down the aisle at their weddings. Khloé was often her greatest defender. “Team Bruce,” she would say, stepping in to defend her step-dad from other family members.

In 2013, the Jenners announced their separation, and Caitlyn moved out. Alone again in Malibu, she started experimenting with gender more frequently; eventually she had her adam’s apple shaved. After the media caught wind of her surgery, she decided to finally go public.

When Caitlyn transitioned in 2015, she moved forward with the same force that once threw her over the finish line in 1976. In doing so, she expanded public awareness of transgender identity in the United States more than any other individual in our nation’s history. In April 2015, more than 17 million Americans watched 20/20’s Bruce Jenner: The Interview with Diane Sawyer, a television event unlike any other. When Caitlyn revealed herself for the first time on the July cover of Vanity Fair, the issue had more than 400,000 newsstand sales—more than double the title’s average, and easily the top seller in 2015. In the months following her debut, she was presented with the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs, and was named one of Glamour’s women of the year.

For a moment, it appeared that Caitlyn had gotten what she’d always craved: acceptance for who she is, and not the person others wanted her to be. “I went my entire life doing everything for everybody else,” she told me. “It was time to take care of me. And so I took on a mission to try to make a difference.”

Even as she received this widespread positive recognition, people in the LGBTQ community began to murmur that Caitlyn Jenner was little more than a spectacle—an embodiment of financial power and exaggerated glamor that threatened to distract America from real issues plaguing the transgender community.

When I met Caitlyn back at her home on Saturday, she had just returned from a lengthy hike on the surrounding mountain paths. She was dressed down in sandals and a T-shirt, headed to pick up a set of clubs from her private golf club.

Sherwood Country Club sits in another upscale neighborhood about 30 minutes from Malibu, nestled in the shadows of the Santa Monica Mountains. The course was designed by Jack Nicklaus, and Tiger Woods used to host a tournament there every year. Caitlyn has been a member for more than 15 years, and she walked the sprawling property like it was a second home. While golf courses have a reputation as the natural habitat of rich, straight, white men, for Caitlyn they have been a sanctuary. Before her transition, it was one of the few places where she could exist. “I would take my little bras up there,” she told me, “in this very quiet golf course, and [see] what it was like playing with boobies.”

Today, Caitlyn can comfortably inhabit spaces here and elsewhere in Malibu as herself—as a wealthy, famous white woman. And while she has faced some harassment because of her gender expression, it tends to be online. But that’s not life for most transgender people, for whom every day can be a struggle for survival, let alone luxury. Transgender people, especially people of color, encounter discrimination, harassment, and violence while seeking employment, housing, and healthcare. When the National Center for Transgender Equality conducted the US Transgender Survey (USTS), the largest survey of its kind, in 2015, nearly 30 percent of respondents were living in poverty, compared to 12 percent of the overall population; the unemployment rate among respondents (15 percent) was triple the national rate at the time of the survey. The disparity is even larger for trans people of color.

That disconnect fuels some of the criticism directed at Caitlyn and her role as a representative of the trans community. “Here’s the deal,” Ashlee Marie Preston, the activist who launched the Change.org petition against Caitlyn’s award, told me in a phone interview earlier this year. “She’s been socialized as a white man most of her life. Period, point blank. At the end of the day, you’re not going to understand the challenges and the barriers to access that not only trans people but trans people of color are facing.”

Hoisting the golf clubs into the back of her car, Caitlyn said she understands why people think she is ill-informed. “I get the criticism that I don’t get it,” she admitted. “You know why? Because I’m not around it.” She hadn’t met a single trans person before her transition in 2015, and then, all of a sudden, she was the most famous trans woman in the world. Her wealth, her politics, her financial ability to use surgery to transform her body, and her racial privilege are commonly cited in arguments leveled against her. “I understand that. But I’m not going to make excuses for that. I’ve worked hard for that. It’s what America is all about. What they don’t realize is that I didn’t have the anonymity to be able to do this privately. I couldn’t.”

Instead, she turned it into a reality show: the docu-series I Am Cait, produced by the same company behind Keeping Up With The Kardashians, premiered on E! on July 26, 2015. During filming, Caitlyn immersed herself with a diverse cast of trans women who guided her through some of the varied cultural realities that trans people live in today. Television viewers watched her attend a memorial for transgender murder victims, meet economically empowered trans women of color with diverse backgrounds, and visit the surviving mother of a trans child lost to suicide.

This process of learning in public wasn’t completely smooth, though, and Caitlyn also made a number of comments that upset the LGBTQ community. In September 2015, her appearance on the Ellen DeGeneres Show stirred controversy when she seemed to show tepid acceptance of marriage equality. A few months later, she told TIME that she takes her appearance seriously in part because “If you’re out there and, to be honest with you, if you look like a man in a dress, it makes people uncomfortable.”

“Along the way, did I make mistakes? Absolutely,” Caitlyn told me. “But I never did it maliciously. I just didn’t know, you know? And I really didn’t realize how critical the community was going to be.”

As the presidential election ramped up, more people began to question Caitlyn on her political beliefs. As early as the fall of 2015, Caitlyn was reaffirming her commitment to the Republican Party, despite its stance on LGBTQ issues, and during the primaries she spoke positively about candidates Ted Cruz and Donald Trump. By March 2016, the second season of I Am Cait featured notably raw conversations about politics between Caitlyn and the progressive trans women on the show, who fired back at her, questioning how she could support a political party widely understood to be destructive to LGBTQ equality.

Caitlyn could have produced a television series that portrayed her in the best light; instead, I Am Cait attempted to do the opposite, encouraging conservative and progressive people to talk out their political disagreements rather than assume the other is wrong and write them off forever.

I Am Cait came to an end after its second season. The following year, Caitlyn started the Caitlyn Jenner Foundation and in some ways her work with the charity picked up where the show left off in continuing her educational journey. “It opens my eyes to the rest of the community,” she told me.

She credits MAC Cosmetics for the idea. In 2016, she partnered with the company on a branded lipstick to benefit the MAC AIDS Fund’s Transgender Initiative. Since then, she has donated more than $2 million to trans organizations across the country through the partnership, while the CJF has awarded a total of $107,500 to five grantees: St. John’s Transgender Health Program, the TransLatin@ Coalition, the Trans Chorus of Los Angeles, APAIT Midnight Stroll Café, and the National Center for Trans Equality (NCTE, which was the advocacy group that conducted the 2015 USTS). With the exception of the NCTE, all of the recipients are based in LA and serve the needs of trans people who live there.

“I like working here in LA because you can kinda see what is going on, you’re right there,” Caitlyn said. “And there are so many trans people here, it’s like perfect. And if we can get something that works here, then we can go to San Francisco… we can watch it go up.”

Though Caitlyn is taking steps to help the transgender community, that effort is hard for many people to reconcile with her continued support of the Republican Party. For years, Republican-controlled statehouses have pushed legislation targeting the trans community, from bathroom bills to “religious freedom” laws that allow anti-LGBTQ discrimination. The party’s official platform for the 2016 election supported such measures, as well as rolling back Title IX protections for sexual orientation and identity and reversing the Supreme Court’s ruling on marriage equality; many advocates called it “the most anti-LGBTQ platform in history.” Caitlyn does not see that as enough reason to abandon the GOP, however, and it didn’t dissuade her from voting for Trump. Over our weekend together, she echoed classic conservative talking points about small government and constitutionalism; while riding in her car, I noticed the radio was tuned to Sean Hannity.

“The Republicans need the most work when it comes to our issues, I get that. I would rather work from the inside.”

“I think it’s good that I’m on the Republican side because the Republicans know that, and I have an immediate in with them to change their minds,” Caitlyn told me, and would mention at various points the meetings she’s taken with conservative lawmakers and administration officials like Betsy DeVos and Nikki Haley. “The Republicans need the most work when it comes to our issues, I get that. I would rather work from the inside. I’m not the type of person who is going to stand on a street corner with a sign and jump up and down. No, I’m going to go have dinner with these people.”

That’s why she flew to the Capitol for Trump’s swearing-in. “I went to the inauguration just because I wanted to meet people. I wanted to be there,” Caitlyn said. One of the people she met was Vice President Mike Pence. “I had a great conversation with him.”

With political divisions as vast as they have become in the US, many Americans might not be so eager to talk with Pence, who has opposed expanding rights and protections for the LGBTQ community throughout his career. Caitlyn, however, saw an opportunity to convince a powerful conservative to rethink some of his views.

“He did some really anti-LGBT community stuff,” she told me. “I know that. He’s also very Christian. He’s kinda like, from our standpoint, the real enemy. But that’s OK, I can handle that.”

Caitlyn says she approached Pence and explained that she, too, is a Christian, a conservative, and someone who “pretty much vote[s] Republican. But I’m also trans. And I said, ‘I would love to share that conversation with you.’ And he looked me right in the eye and said, ‘You know what, I would love to do that.’”

When I asked Caitlyn if that happened yet, she said that it hadn’t due to difficult schedules, before jumping into an anecdote—like with Pence, one she had already recounted publicly—about Trump inviting her to play golf. Caitlyn does concede that Trump “has been, for all LGBT issues, the worst president we have ever had,” and says she could not support him for reelection.

“I want him to know politically I am disappointed, obviously. I don’t want our community to go backwards,” she said, her voice thin with resignation. “Just leave us alone, that’s all we want. Then maybe later down the line, we can get somebody a little better.”

Would she vote for a Democrat? Caitlyn demurred: “I don’t know who in the Democratic Party. I would look at it. I don’t vote parties. I vote the person.”

Caitlyn says she wants to help the trans community rise, and she wants to transform the Republican Party to be accepting of gender variance. But gender variance is not the only issue that matters, and political resentment to it is not the only problem impacting transgender communities. The Republican attack on Obamacare threatens to leave trans Americans without healthcare. The administration’s stance on immigration is also unsettling for trans people who come to the United States seeking a better life. The treatment of trans prisoners who are under ICE detention is reportedly abysmal, and though that had been a problem even under the Obama administration, people fear that conditions for immigrants will become worse under Trump as he continues to crack down on and vilify undocumented immigrants in the United States.

So even if Caitlyn manages to get Republicans to be more open to progressive ideas about transgender policies, there are many political issues fundamental to the party that would continue to devastate impoverished communities of trans women, particularly those of color. To her critics, Caitlyn has been unable to shake her reputation as an ally of the conservative establishment and, therefore, is ultimately damaging the cause she says she cares about.

“The money means nothing if she is going to continue to support political statements that work against us and make our jobs harder,” Ashlee Marie Preston, the writer and activist, told me.

Preston once worked as editor-in-chief of the intersectional feminist publication Wear Your Voice, and briefly considered running to represent California’s 54th State Assembly district in Los Angeles. She is best known for a viral cellphone video filmed last August, in which she confronts Caitlyn after a performance by the Trans Chorus of Los Angeles, telling her that she is a “fucking fraud” with no place in the transgender community because she supports the Republican Party and voted for Trump. Caitlyn listens, then tells Preston, “You don’t know me.” The video immediately garnered wide media coverage and support online. The author Janet Mock described Preston’s action as “free labor.”

Just a few weeks later, St. John’s Well Child & Family Center announced it would present Caitlyn with an award at Eleganza, a fundraising gala capping off its annual TransNation Festival in October. One week before the event, Preston launched her Change.org petition. It, too, spread quickly on social media, and some trans women in LA got caught in the crosshairs. In one social media attack, Preston referred to black trans activist Chandi Moore as “Caitlyn’s house slave” after Moore came to Caitlyn’s defense on Facebook. As a result, some trans women Broadly spoke to said they were nervous to publicly discuss Caitlyn. However, some people who were closest to the Eleganza event were willing to speak.

St. John’s Well Child and Family Center’s transgender health program is located in a clinic on 23rd St. in South Los Angeles. Palm trees tower overhead, casting long shadows on the sidewalk. Inside, a wide hallway opens into a waiting room bright with natural light. All but a few of the chairs were filled on the day I visited. As a television played on the wall, a trans woman walked up to the reception desk, smiled, and signed in.

After a couple minutes, Diana Feliz, then manager of St. John’s Transgender Health Program, came to greet me. We had met before when I was in Los Angeles reporting on a charitable trans beauty pageant that St. John’s put on for the 2016 TransNation Festival. Caitlyn was one of the judges that year, but her presence seemed less divisive than it was at Eleganza, now a year later; I only heard a few negative murmurs from the crowd when she took the stage in 2016.

As Feliz took me through the clinic, she explained the broad array of services that St. John’s provides for the trans community in and around LA, such as primary medical care and mental health treatment, as well as transition-related care like hormone therapy. They also offer letters of recommendation for gender-affirming surgeries, which are typically required by surgeons, and case management services including assistance with changing your name or gender marker on legal documents. St. John’s is such a valuable resource because of the comprehensive nature of the program—they don’t just help their clients transition and stay in good health, they also offer programs to assist people in finding jobs or obtaining an education in order for disenfranchised community members to have a better future.

The program was started in 2013 as a response to the unmet need for accessible medical care for trans people. The barriers are economic as well as social. For example, while the Affordable Care Act prohibits anti-transgender discrimination, the 2015 US Transgender Survey found that one in four respondents still encountered problems with insurance. One third of USTS respondents who had seen a medical provider that year reported having at least one “negative experience” due to their gender identity, including “being refused treatment, verbally harassed, or physically or sexually assaulted, or having to teach the provider about transgender people in order to get appropriate care.”

Without reliable access to healthcare, trans people are exposed to myriad health risks, and the consequences are devastating. Studies suggest trans individuals are living with HIV at higher rates than the rest of the population, with the disparity most extreme for trans women of color. They also experience depression, anxiety, and other psychological distress at higher rates. Forty percent of USTS respondents said they had attempted suicide in their lifetimes—nearly nine times the rate in the US population.

Clients receive care at St. John’s regardless of their ability to pay. “Nobody is turned away,” said Jim Mangia, the president and CEO of St. John’s, which takes us to the issue at hand. “Everything we do requires fundraising.”

While most of St. John’s revenue comes from patient services and premiums, according to its publicly available financial statements, contributions and grants do fund a significant portion of the organization’s work. Every dollar matters, and the financial support of a celebrity is not something that they are in a position to refuse. Last April, St. John’s was approached by the Artemis Agency, a philanthropic consulting firm, on behalf of an unnamed client. Feliz didn’t know it was Caitlyn until the day she came to visit the clinic.

“She’d just started the Caitlyn Jenner Foundation so she can help trans organizations, and she said she wanted St. John’s to be the first recipient,” Feliz recalled. It was a surreal moment for Feliz and her team. Caitlyn didn’t just want to discuss funding them—she was ready to make a donation immediately. “I was stunned,” Feliz said. “I had never received a $25,000 check.”

According to St. John’s, Caitlyn’s was the first individual foundation to make a significant donation to the Transgender Health Program. “I think it was noticeable that she was evolving as a trans woman,” Feliz told me. “Maybe not as fast as people wanted to see, but everyone transitions at their own pace. There’s no right or wrong. Have there been mistakes? Of course. I’ve made mistakes! Everybody has.”

In October, St. John’s announced its decision to honor Caitlyn with the Sustaining Vanguard Award at Eleganza . “The Caitlyn Jenner Foundation has stepped up to support our burgeoning transgender health project,” Mangia said in a statement at the time. “At St. John’s, we believe in service and advocacy. We have never shied away from political controversy or doing what we thought was right for the populations we serve. And we believe that when people of differing views can come together for a dialogue, we can make true progress together.”

The backlash was swift and intense. One week before Eleganza, St. John’s hosted a community meeting where trans people came to share their feelings. Preston was there, as were people who supported her, and others who have felt targeted by her, according to one report.

Though it was a night of healing, it was also a difficult night. People were upset. “I think the whole situation was very unfortunate,” Mangia told me at the clinic. “Our intent was not to hurt the trans community, and we were very sorry that some members of the community found that decision [to give the award] controversial.”

A few days later, St. John’s and Caitlyn announced, through separate press releases, that she would not attend Eleganza or receive an award.

The outrage and the hurt were nowhere to be found at the actual Eleganza event that Saturday night; the ire of the internet stayed online. Staff looking trim in tuxedos and pearls ushered guests in sequins and miniskirts into Downtown LA’s Cicada Club while celebrities like Laverne Cox and Candis Cayne walked the red carpet. Jazzmun Crayton was there to accept the Marsha P. Johnson Trailblazer Award for a lifetime leading the way for transgender actors and performers. Trans men and women of all races and backgrounds poured into the hall, electrifying the room with a novel vibrance. It felt like a family gathering, which isn’t uncommon in my experience. When trans people gather in unity, there is a sense of collective achievement: In a world that has ruthlessly sought our extinction by means both violent and political, we are powerful when we come together to celebrate our beauty, our tenacity, and our lives.

Watching the party unfold, I realized the irony in Preston’s protest. In criticizing how Caitlyn overshadowed Eleganza and stole attention from Crayton, she’d ended up inflating Caitlyn’s presence, casting the very shadow she had warned would fall. It was “disheartening,” Diana Feliz told me at St. John’s, to watch the social media discourse focus on Caitlyn instead of the Transgender Health Program, or on the team of people who made Eleganza possible, or on Crayton and her accomplishments.

Crayton herself was nonplussed at the idea of sharing a stage with someone like Caitlyn; as she told me later, “No one can steal my light.” What did concern Crayton was how the transgender community in LA treated one another, including Caitlyn.

“We are fucking amazing, smart, loving, gifted, kind, generous people,” she exclaimed, clenching her fists in excitement. “We take care of your family, we feed you, we wash your clothes, we take care of your home, we design your hair and makeup, we give you your voice. Don’t fucking discard us. But we definitely gotta find a way not to discard each other.”

While Caitlyn has been targeted because of her wealth and status, Crayton told me that it’s actually something that she admires, and would like more trans people to achieve. “I’m not gonna ever disrespect Miss Caitlyn’s journey. Never,” she said. “I need her to be who she is. I need her to be in Malibu, at that house—I need to know that it’s possible.”

Back in Malibu the day after Eleganza, that house was as quiet as ever, the silence only broken by Caitlyn calling out to her dog, Bertha.

“I spend a lot of time by myself here in the house,” she said. “I have a lot of children, but sometimes just because of circumstances, maintaining a close relationship with your kids is very tough. They all have lives. They’ve all moved on.”

“We’re just human beings; we’re going to be here for a very short time,” Caitlyn later added. “We come and we go and at the end, when it’s all said and done, hopefully your family is going to be there.”

Back when she was Bruce, before she thought she could transition, she wanted to stipulate in her will that she was to be buried in women’s clothes. Unable to imagine a life for Caitlyn, she imagined her death. “I thought about that a lot over the years,” she told me. “And it would shock everybody. Screw ‘em.”

Now that she has found her place as a woman in the world, her outlook has changed: “I hope when I get up there to the pearly gates, God looks down and says, ‘You did a good damn job, you won the Games, raised wonderful children, and you know, you made a difference in the world. Yeah, come on in.’ That’s the way I want to go.”

There will never be another Caitlyn Jenner. She rose to international fame as a representative of American manhood in the last quarter of the 20th century, and then in the flip of a television channel dragged the nation into the 21st by introducing every household to a transgender person. It would be impossible to illustrate the evolution of gender in the United States without recognizing the rise and fall of Bruce and Caitlyn Jenner.

“We come and we go and at the end, when it’s all said and done, hopefully your family is going to be there.”

Her story is also emblematic of the push and pull in our divided nation. A transgender celebrity who voted for Trump and continues to associate with the Republican Party, she does not easily fit into one ideological box for conservatives or liberals. Caitlyn Jenner makes people uncomfortable. She is also a human being, a product of her generation, who is trying her best to do the right thing for her community, and for herself.

As the sun set on Sunday evening, Caitlyn and I walked the grounds outside her home, following a dirt path lined by tall grasses. Standing there in the approaching twilight, Caitlyn told me about how she piloted a small plane out of Los Angeles earlier that week. She likes to fly, to be alone among the clouds.

Years ago, when Bruce was at his lowest, Caitlyn would materialize in the sky, coming into being on lonely flights to nowhere. She says she kept a wig and set of women’s clothing in her plane so that she could go somewhere to be herself, even if it couldn’t be on Earth. “I would be up there in my little lonesome, free as can be,” Caitlyn said. Maybe she felt closer to God.

Sometimes, Caitlyn told me, she would turn her plane vertically, hurtling at hundreds of miles per hour straight up into the sky before she would stop, float briefly in the air, and fall back down.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE