Is Rocket League a video game or a digital sport?

It’s both. The game has amassed 35 million players in two years for its zany car-soccer fun, while the burgeoning competitive scene—led by the Rocket League Championship Series (RLCS)—has made strong inroads in the esports world. But with last week’s Autumn Update, developer Psyonix has nudged the experience more towards the latter by standardizing the dimensions of every arena in the game’s public online modes.

Videos by VICE

The move has been well received by most professional players, and it’s a long time coming. Most of the game’s core arenas already share the same size and shape: a rounded rectangle that lets players drive up the walls and to the ceiling. It’s that consistency of surfaces and curves between venues that allows pros to anticipate bounces and pull off dazzling shots and plays. But a few months after the game’s release, Psyonix started playing with alternative shapes and modifications for maps that soon appeared in both the competitive and casual playlists.

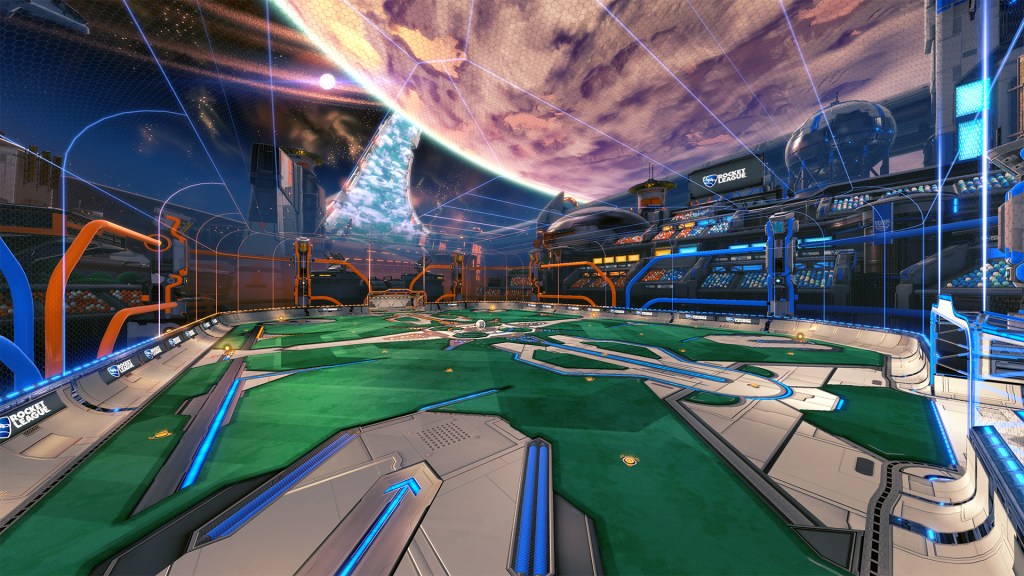

First was Wasteland, a wider, sand-covered rectangular space with uneven surfaces and unfamiliar curves that affected the ball’s bounces. By and large, the competitive community hated it. But Psyonix pressed on: the urban Neo Tokyo added elevated ridges to the sides of the arena, vaulting speedy drivers awkwardly into the air, while the outer space-themed Starbase ARC swapped the rectangle for an octagon. Fans’ gripes about the inconsistencies between arenas only grew with each new addition.

Now Psyonix has changed course. Wasteland and Starbase ARC have been replaced with arenas that keep the familiar visual themes, but swap in the same dimensions as every other competitive arena (Neo Tokyo was previously converted). Non-standard arenas won’t appear in the online playlists anymore—only in private and offline matches—and future arenas will share the same dimensions as the others. Rocket League‘s pitches can take any shape or form that the developers dream up, but they’ve decided that one size should fit all in the online playlists.

Why the change of heart? According to the studio’s announcement, community feedback ultimately tipped their hand. “We see Rocket League as a digital sport,” reads the post. “As such, we think standardization is important and necessary to provide a level playing field and foster consistent competition across all skill levels and events.” Furthermore, they concede that non-standard maps “have not been embraced,” and with the rise of Rocket League esports, they “no longer feel that map variety is needed or appropriate for the competitive scene.”

Many players are keen on the decision, and have long advocated for it. It’s “by far the best thing they could do,” says Mock-It Esports player Philip “Paschy90” Paschmeyer, an RLCS grand finalist in season two. “It’s impossible to consistently predict wall bounces from non-standard maps while also being aware of the different shape of the map itself. I still ’til this day have problems on Wasteland predicting the walls and the floor, since it’s not straight. So I am really happy that Psyonix has listened to most of the competitive players that obviously hated non-standard maps.”

It was a common sentiment shared across social media when Psyonix announced the news in late August, but there are key outliers. Season two RLCS champion Mark “Markydooda” Exton of FlipSid3 Tactics taunted supporters of the decision with a profane tweet, writing, “No longer will you be demoralized by your own shitness in the face of learning something new.”

Ryan “Doomsee” Graham of Team Infused admits that he likes the variety provided by the maps—”Except Wasteland, screw that map”—but agrees with Markydooda’s notion that players’ lack of skill on those maps colors their perspectives. “There are a lot of people that don’t like the maps simply because they’re bad on [them],” says Doomsee. “They’ve barely played on different maps, so they find it difficult to understand how the ball interacts with walls that aren’t standard, when the physics are all exactly the same.”

When you standardize all maps for competitive play and make them all the same with a different skin on top, what are you really accomplishing? What’s the point of calling it an esport? There’s no difference from mainstream sports at that point. — Michael “Achieves” Williams

That lack of experience may have largely shaped the community’s generally negative view of non-standard arenas. Professional players have logged thousands of hours in Rocket League, and most of the game’s maps (before this update) used the same layout and dimensions. Comparatively, non-standard maps only popped up every so often in the randomized ranked playlists, and as such, players had little consistent opportunity to learn those layouts in high-level competition. That left these high-flying car-soccer stars feeling out of their element.

“High-level Rocket League requires you to predict where the ball’s going to be and how it will bounce in a huge variety of scenarios,” says Psyonix’s design director, Corey Davis. “Players master that skill over hundreds or thousands of hours of practice. Invalidating all of that practice time with differently sloped or shaped walls and floors is a big downside, and the non-standard arenas themselves ultimately didn’t create enough strategic or tactical differences to justify that.”

When there’s thousands of dollars and organizational sponsorships on the line in the RLCS and other tournaments, pro players demand that consistency. And if they can’t anticipate bounces and movements, then we see sloppier play as viewers, despite their considerable mechanical prowess. On rare occasion, teams have picked non-standard maps for their RLCS match-ups, usually in the hopes of tipping the scales against a stronger team. But in every single instance, according to RLCS analyst and caster Adam “Lawler” Thornton, that team has lost anyway. It was never worth the time for any serious pro team to master those off-brand layouts.

If Rocket League had implemented different arena dimensions from the very start, then maybe this wouldn’t be a discussion. But Wasteland came late, and top pros had already invested several months of play between the finished game and the earlier alpha and beta test periods. The standard had been established, and all the tweaks that came after were widely rejected.

Or maybe those non-standard maps just weren’t very compelling. Hollywood Hammers coach and player Matt “Loomin” Layman is all for arena variety, but says that Wasteland and Neo Tokyo “weren’t very good maps in general” and believes that some of their changes were too major. He agrees that the timing affected the perception, but also suggests that less severe additions to the standardized shape—like adding boost pads to the ceiling, or extending the length or height of the arena—might resonate better with players.

“On the other hand, it would be interesting for Psyonix to scream ‘YOLO’ into the night and create a map that just pushes the insane-ness of an arena,” Loomin says. “Let’s add as many obstacles, ramps, and objects into a weird triple-decker arena and just see what happens. Right now, I think they have created non-standard maps in this weird middle ground of being just different enough to be annoying.”

Making the comparison to physical soccer is no great stretch, and while real-life professional pitches may vary to some degree, they’re all similar in overall shape and built within guidelines. Certainly, soccer still enthralls fans today, as the modern sport has for over 150 years. Given Rocket League‘s esports rise, it’s easy to point to that real-world equivalent and disregard the need for oddly-shaped arenas.

But why not use the medium of video games to go nuts with arena designs and really stretch the definition of what’s possible with car-soccer? Rocket League isn’t bound by physical structures and vast expenditures, and introducing different arenas could bring a new layer of strategy to an incredibly fast game that’s mostly centered on reading a moment and reacting.

“Why would you ever want to settle for just another sporting event in a standardized stadium?” asks Rocket League Rival Series analyst Michael “Achieves” Williams. “When you standardize all maps for competitive play and make them all the same with a different skin on top, what are you really accomplishing? What’s the point of calling it an esport? There’s no difference from mainstream sports at that point—it’s just soccer with cars.”

Williams uses the phrase derisively, but “just soccer with cars” is the no-nonsense pitch that has guided Rocket League into millions of homes, ESPN’s X Games, and NBC Sports. Ultimately, there’s no pleasing everyone: one player’s variety is another’s lack of consistency. But the analysts I spoke with worry that sticking with standard maps will ultimately limit Rocket League‘s skill ceiling, and perhaps eventually turn off viewers.

“I personally feel that we’re limiting the potential in the end. The beauty of this game is how creative players are getting even without map diversity,” says Thornton, pointing out makeshift moves like wave dash recoveries and jump resets that players have concocted within the game. “The ability to add unique styles of maps that specialize in one area of play or another may heighten the skills of players even more. It would give them another thing to practice and work towards, but a lot of pros feel that would be time wasted. Spending time playing on a nonstandard map is time wasted not playing on a standard map.”

And those players’ wish is Psyonix’s command. Davis says the long-term potential for lacking variety is “an acceptable tradeoff for the positive benefits of standardization” in the studio’s view, and sticking with the rounded rectangle is the mandate going forward. Besides the reformed locales, the Autumn Update added one totally new map: Farmstead, a sun-drenched rural arena. And yes, it’s standard, just like the rest of them.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Sega -

Screenshot: NetEase Games -

Screenshot: NetEase Games -

Screenshot: Theorycraft Games