There’s a longstanding theory in game development that sounds like a joke but is a very real phenomenon: Time to Penis. It’s the measure of how long it takes users to create a dick in-game. LEGO Universe allegedly had a whole team working on its TTP problem. Second Life residents made genitalia for their avatars before the game got out of beta. SimCity, Minecraft, Call of Duty—name a game, and players have put a dick in there.

No game or platform is immune to TTP, because no world is immune. It’s in our nature to christen the freshly-driven snow of untouched lands with lewd little doodles: just four months after humans set foot on the moon for the first time, we left a dick drawing on its pristine surface. We pondered that orb for hundreds of thousands of years, and when finally given the chance to touch it, we stamped it with a cartoon dick. If we’re given the tools to create in a virtual environment, dicks are inevitable.

Videos by VICE

Last month, Mark Zuckerberg announced that he thinks he can create his own metaverse, and his head of virtual reality, Andrew Bosworth, said he’s aiming to institute “almost Disney levels of safety.” Facebook, as a company, is incredibly hostile toward all things sex. If Facebook doesn’t carry its anti-sex terms of use over to the metaverse, the time-to-penis would probably set a speed record. And if he refuses to allow sexuality to be a part of his metaverse for adult users, it’ll suck as much as Facebook already does.

If Facebook is actually aiming to build a virtual reality that will supplant many of the ways we communicate and move through the world today, is it going to change the anti-sex policies that have defined it so far, or create a dystopia where sex doesn’t exist?

*

The metaverse did not spring fully formed from Mark Zuckerberg’s $121.6 billion forehead. Yes, the concept of a metaverse—a digital dimension where people exist as non-corporeal avatars online—was originally the idea of science fiction author Neal Stephenson, as part of his 1992 book Snow Crash. But in the 30 years between that book and now, people have created constellations of actual virtual worlds, building complex, vibrant communities where residents live rich lives parallel to their physical one. In most of those communities, sex has played a defining part. What happens when a company that’s hostile to all things intimate tries to take over the metaverse?

Angelina Aleksandrovich, founder of sex-positive virtual reality community RD Land, told me that people involved in building virtual reality communities have seen Zuckerberg’s latest project coming for a long time. New discussions about the metaverse have been both welcome and disheartening, she said.

“There’s more attention from the public and from investors on the metaverse-development space as a whole, but metaverse has also become something of a buzzword,” she said. “It’s also a bit sad to see that the ideas me and my co-workers (and so many people before us) had discussed and imagined about the future of the internet and VR many years ago are only now becoming more or less familiar concepts to the mainstream users as the intellectual property of Zuckerberg,” Aleksandrovich said.

Facebook hasn’t revealed much about how its virtual world will work. What most of the consumer public knows about how it will actually operate is cobbled together from marketing copy, highly produced concept videos, and Zuckerberg’s goofy morning talk show appearances.

A spokesperson for Meta told me that much of what the company is envisioning “will only be fully realized in 5-10 years.”

“We’re discussing it now to help ensure that any terms of use, privacy controls or safety features are appropriate to the new technologies and effective in keeping people safe,” they said. “This won’t be the job of any one company alone. It will require collaboration across industry and with experts, governments and regulators to get it right.”

Based on how it has moderated the biggest social media platforms in the world, we can assume that it will be an entirely sexless world. Facebook has been banning nudity as early as 2008, when it started deleting users’ posts that included female nipples. It’s only gotten more strict, to the point where now, showing a little too much cartoon skin will result in a ban from running ads on the site, and in some cases, even if users play by its rules, Instagram will punish them anyway, taking away important features or kicking them off entirely.

But all of the lasting virtual worlds of the last 30 years have included sex—whether developers turned a blind eye to users doing the dirty, or created platforms to explicitly foster sexual shenanigans. Some of the earliest text-based internet communities of the 1990s, Multi-User Dungeons, were full of adult roleplay. Residents of those communities met, dated, and married in real life because of the time they spent online. These worlds usually weren’t built exclusively for cybersex, but it still emerged in private messages and hidden rooms.

When graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing games came along, such as Everquest in 1999 and Second Life in 2003, players got visual bodies to walk around in. Second Life’s reputation for hosting vast sex clubs and endlessly customizable genitalia (and poses to go with them) has preceded it for years. One of the most infamous moments in Second Life happened when residents interrupted a live, in-world interview by spamming the scene with dancing, flying penises. The world has separate areas that are explicitly marked as being for adults, but Twitch banned people from live-streaming it in 2015. Yet the developers never tried to stop residents from developing user-generated content around sexual themes—there are currently 258 adults-only worlds in Second Life, 8,876 items matching “penis” for sale in the marketplace, and 4,591 under “vagina.”

Second Life is 18 years old, but still hosts a thriving community of people who show up every day, make things, meet people, earn money, and yeah, have sex—sometimes all at the same time, just like sex is one part of life away from the keyboard. It also has a vibrant adult economy, including strip clubs and escorts.

John Carmack, former CTO and current consultant at Oculus, said in his Facebook Connect keynote in October that “setting out to build the metaverse is not actually the best way to wind up with the metaverse.” He goes on to say that since Zuckerberg has decided “now is the time” to build the metaverse, money and resources will start pouring into making it happen.

“My worry is that we could spend years, and thousands of people possibly, and wind up with things that didn’t contribute all that much to the ways people are actually using the devices and hardware today,” Carmack said. But the way people are using VR now is a lot more fun than the Disneyfied, corporate vision Facebook has for its metaverse: they’re in virtual social platform VRChat generating their own worlds and avatars and running around as anime catgirls, in Second Life creating sex-positive clubs, or watching VR porn—an industry that was once expected to be VR’s “killer app,” and is still growing.

Wherever people gather online, some of them will want to fuck, and where there’s a way to text, talk, or gesture, they’ll find a way to do it. So what will Facebook’s metaverse be without sex?

If virtual worlds are meant to reflect the wildest dreams of away-from-keyboard societies, sexuality is an inextricable part of that. In meatspace, sexual speech and sex industries can be squashed under conservative attempts at controlling the populace, but it doesn’t go away. In digital realms, it can be banned under community guidelines, but users find a way to eke it out somewhere else—in private channels and rooms or locked forums.

In a demo interview with the Facebook founder, the first thing CBS anchor Gayle King says when she enters virtual reality and turns to face Zuckerberg is, “You’ve got freckles on your nose!”

“I’ve got freckles in real life, too, so just trying my best with the avatar,” he replies. By implying that the coolest thing about their metaverse is the ability to directly replicate your physical self in the virtual world—creating a parallel universe, instead of an alternate one—Facebook is missing a major draw of online embodiment, for most people: the ability to be weird as hell online.

A fan edit of the CBS interview, where Zuckerberg says “check this out” and two huge breasts spring from his avatar’s chest, is extremely funny but also shows how people often choose to inhabit virtual worlds. Not boobs per se (well, a little boobs), but the freedom to express themselves however they want.

They were demoing Horizons Workrooms, a VR workspace Facebook plans to launch as part of its grand metaverse. It makes sense in that environment that you wouldn’t want coworkers cropping a pair of triple D’s in the middle of a board meeting. At work, you mostly want people to be consistently recognizable. Other Meta demos do hint at there being appearance options beyond the literal, however; in one, Bosworth is a big red robot, while everyone else is their realistic, human selves.

“The whole beauty of the metaverse is the chance to step outside of our human bodies and real world identities we choose or, depending on circumstances, are forced to live in.”

But even if realism isn’t a requirement, the company is pushing the idea that matching your physical and virtual appearances is part of the supposed appeal. A big part of this effort is Codec Avatars, a project that’s part of Facebook’s VR/AR research department Reality Labs. The avatars coming out of Codec are all about realism, down to seeing the pores on a person’s face. Yaser Sheikh, the Director of Research at Facebook Reality Labs in Pittsburgh, said in a company blog post that his team gauges success based on an “ego test,” or a “mother test:” the idea that “you have to love your avatar and your mother has to love your avatar before the two of you feel comfortable interacting like you would in real life.”

Avatars that look realistically like your physical self are a clever psychological trick on Facebook’s part. Most people gravitate toward creating characters in games that look like themselves; everyone wants to be the protagonist in their own story, and researchers have found that when people create realistic avatars, they feel more connected to them. Some researchers are already wondering if the urge to create perfected, idealized selves will lead to more body dysmorphia among young people. But in virtual worlds, users also commonly experiment with gender, to ease the dysmorphia they feel in the “real” world—virtual gender presentation can help players better understand their real-life gender presentation and sexual identities, before they’re able to be out in person. People have been doing this since the days of MUDs, and still do today.

“The whole beauty of the metaverse is the chance to step outside of our human bodies and real world identities we choose or, depending on circumstances, are forced to live in. We no longer have to comply with the biological nature or a lack of resources to self-express our inner being as we wish,” Aleksandrovich said. Letting users choose mutable, anonymous avatars has been important to the kinds of virtual spaces she wants to encourage—where it’s safe to talk about sexuality, gender, kink and pleasure. “In our spaces I witnessed people like that coming out as queer in their late 50s and 60s, confronting and sharing their repressed desires and old traumas, but also things they never told anyone fearing the judgment,” she said. “They may not be ready for this healing in the physical world, but they can allow that to happen in the virtual space because they know that at any point in time they can change the name and the look of their avatar and no one will ever connect the dots that it was them.”

Zuckerberg seems to understand this, at least on a theoretical level. “You’re not always going to want to look exactly like yourself,” he said in a Codec portion of one presentation. “That’s why people shave their beards, dress up, style their hair, put on makeup, or get tattoos, and of course, you’ll be able to do all of that and more in the metaverse.”

The question is whether people will want to. “The main limiter with adult content, or even a lot of other kinds of content, is that people are going to be hesitant to express themselves in a virtual space knowing that people could probably pretty easily figure out who they are in real life,” Second Life journalist Wagner James Au told me. “Someone could say, ‘hey, I saw you at the furry orgy last week, Mr. CEO or whatever.’ So that would be another challenge.” Perhaps users will have worksona and playsona avatars to switch between, but that hasn’t been the case with Oculus logins so far. And your choices in the metaverse will surely be grafted into Facebook’s bigger picture of who you are across all of its other platforms, and the entire internet.

A metaverse needs to give the tools of creation to its inhabitants in order to be successful. Even in Stephenson’s vision of the metaverse, this was important: “You can look like a gorilla or a dragon or a giant talking penis in the Metaverse,” he wrote in Snow Crash. “Most hacker types don’t go in for garish avatars, because they know that it takes a lot more sophistication to render a realistic human face than a talking penis.” Boobs, too, come in sizes “improbable, impossible, and ludicrous.”

People who have influenced successful virtual worlds support this idea. At a games developer conference in 2002, Raph Koster, lead designer of one of the earliest MMORPGs Ultima Online, told anyone being overly precious about user-generated content to “get over yourselves; the rest of the world is coming.” Second Life founder Philip Rosedale recently said in an interview: “I think the reason why tens of millions of people tried [Second Life] out was the promise of the ability to be creative and expressive in a realistic, lifelike domain.” Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus VR, tweeted following Facebook’s metaverse news that if this new metaverse “doesn’t support custom geometry, it isn’t The Metaverse.”

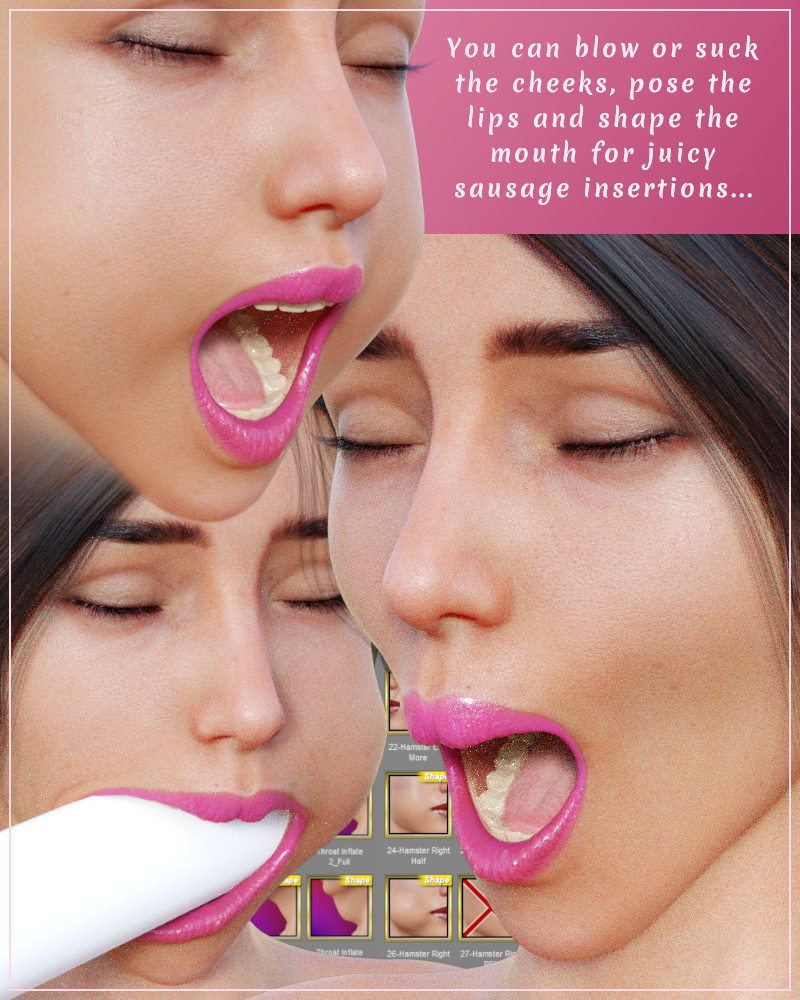

The problem is that if you’re going to let people make “custom geometry,” inevitably some of them are going to make foot-long nine-boned tongues, penises with monster faces for the heads, and something called “Pussyface.” There’s already a thriving community of people making 3D rendered custom avatars, and they’re not a monolith, either—mostly, they’re creating these things for fun and kink, but sometimes for more questionable purposes, like elaborate revenge fantasies or non-consensual porn. A metaverse where people are free to create whatever they want has to carefully draw the line between consensual kink and abuse in a world where it’s sometimes hard to tell these things apart even if you try your best. Historically, Facebook’s policy has been to simply ban anything that is even remotely sexual, which is not how lasting virtual worlds have functioned so far.

To prevent TTP, developers would have to suppress all users’ ability to customize or create new content—something that’s been central to most metaverse-style games, including the most popular apps on Oculus, like Rec Room, and VRChat, where the whole point is to make weird shit and talk to other people. People keep coming back to Second Life after all this time because it’s a world that’s constantly changing; it’s a new game every day.

If Facebook’s track record is any indication, it will bring its old ways with it. In an internal memo obtained by the Financial Times, Bosworth wrote that to get those Disney-levels of safety, moderating users’ behaviors “at any meaningful scale is practically impossible.” What we got when Facebook faced this problem of moderation on a massive scale: algorithms that kick off all forms of sexual speech (while somehow still missing huge amounts of actual child sexual abuse material), biased against queer people, trans people, people of color, sex workers and sex educators.

Even if Facebook allows adult content in its metaverse, it would have a hard time earning users’ trust after years of suppressing all sexual speech after all this. Other big tech VR ventures are already grappling with these problems; Aleksandrovich recently ran into this problem with Microsoft-owned AltspaceVR. A Burning Man inspired event she’d helped organize and was hosting for 18+ members was forced to go private, and then shut down entirely, even though she felt the content was within the platform’s rules as educational, not pornographic. (AltspaceVR’s terms of use forbid “objectionable, obscene, offensive, pornographic,” and “vulgar” content, the definitions of which are up to the company’s sole discretion.)

This, to her, is just another reason why it’s so important to keep building, even as Zuckerberg tries to continue taking over the internet.

“Our core values of the space and the community we are building is a radical self expression, open mindedness, freedom of opinions, actions and creative expression, community ownership, privacy, security, peer support, inclusivity, sex & body positivity,” Aleksandrovich said. “Basically everything that Facebook is not.”