This spring, Facebook reached out to a few dozen leading social media academics with an invitation: Would they like to have a casual dinner with Mark Zuckerberg to discuss Facebook’s problems?

According to five people who attended the series of off-the-record dinners at Zuckerberg’s home in Palo Alto, California, the conversation largely centered around the most important problem plaguing the company: content moderation.

Videos by VICE

In recent months, Facebook has been attacked from all sides: by conservatives for what they perceive is a liberal bias, by liberals for allowing white nationalism and Holocaust denial on the platform, by governments and news organizations for allowing fake news and disinformation to flourish, and by human rights organizations for its use as a platform to facilitate gender-based harassment and livestream suicide and murder. Facebook has even been blamed for contributing to genocide.

These situations have been largely framed as individual public relations fires that Facebook has tried to put out one at a time. But the need for content moderation is better looked at as a systemic issue in Facebook’s business model. Zuckerberg has said that he wants Facebook to be one global community, a radical ideal given the vast diversity of communities and cultural mores around the globe. Facebook believes highly-nuanced content moderation can resolve this tension, but it’s an unfathomably complex logistical problem that has no obvious solution, that fundamentally threatens Facebook’s business, and that has largely shifted the role of free speech arbitration from governments to a private platform.

The dinners demonstrated a commitment from Zuckerberg to solve the hard problems that Facebook has created for itself through its relentless quest for growth. But several people who attended the dinners said they believe that they were starting the conversation on fundamentally different ground: Zuckerberg believes that Facebook’s problems can be solved. Many experts do not.

*

The early, utopian promise of the internet was as a decentralized network that would connect people under hundreds of millions of websites and communities, each in charge of creating their own rules. But as the internet has evolved, it has become increasingly corporatized, with companies like Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, and Twitter replacing individually-owned websites and forums as the primary speech outlets for billions of people around the world.

As these platforms have grown in size and influence, they’ve hired content moderators to police their websites—first to remove illegal content such as child pornography, and then to enforce rules barring content that could cause users to leave or a PR nightmare.

“The fundamental reason for content moderation—its root reason for existing—goes quite simply to the issue of brand protection and liability mitigation for the platform,” Sarah T. Roberts, an assistant professor at UCLA who studies commercial content moderation, told Motherboard. “It is ultimately and fundamentally in the service of the platforms themselves. It’s the gatekeeping mechanisms the platforms use to control the nature of the user-generated content that flows over their branded spaces.”

To understand why Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Reddit have rules at all, it’s worth considering that, as these platforms have become stricter, “free speech”-focused clones with few or no rules at all have arisen, largely floundered, and are generally seen as cesspools filled with hateful rhetoric and teeming with Nazis.

And so there are rules.

Twitter has “the Twitter Rules,” Reddit has a “Content Policy,” YouTube has “Community Guidelines,” and Facebook has “Community Standards.” There are hundreds of rules on Facebook, all of which fall into different subsections of its policies, and most of which have exceptions and grey areas. These include, for example, policies on hate speech, targeted violence, bullying, and porn, as well as rules against spam, “false news,” and copyright infringement.

Though much attention has rightly been given to the spread of fake news and coordinated disinformation on Facebook, the perhaps more challenging problem—and one that is baked into the platform’s design—is how to moderate the speech of users who aren’t fundamentally trying to game the platform or undermine democracy, but are simply using it on a daily basis in ways that can potentially hurt others.

Facebook has a “policy team” made up of lawyers, public relations professionals, ex-public policy wonks, and crisis management experts that makes the rules. They are enforced by roughly 7,500 human moderators, according to the company. In Facebook’s case, moderators act (or decide not to act) on content that is surfaced by artificial intelligence or by users who report posts that they believe violate the rules. Artificial intelligence is very good at identifying porn, spam, and fake accounts, but it’s still not great at identifying hate speech.

The policy team is supported by others at Facebook’s sprawling, city-sized campus in Menlo Park, California. (Wild foxes have been spotted roaming the gardens on the roofs of some of Facebook’s new buildings, although we unfortunately did not see any during our visit.) One team responds specifically to content moderation crises. Another writes moderation software tools and artificial intelligence. Another tries to ensure accuracy and consistency across the globe. Finally, there’s a team that makes sure all of the other teams are working together properly.

“If you say, ‘Why doesn’t it say use your judgment?’ We A/B tested that.”

How to successfully moderate user-generated content is one of the most labor-intensive and mind-bogglingly complex logistical problems Facebook has ever tried to solve. Its two billion users make billions of posts per day in more than a hundred languages, and Facebook’s human content moderators are asked to review more than 10 million potentially rule-breaking posts per week. Facebook aims to do this with an error rate of less than one percent, and seeks to review all user-reported content within 24 hours.

Facebook is still making tens of thousands of moderation errors per day, based on its own targets. And while Facebook moderators apply the company’s rules correctly the vast majority of the time, users, politicians, and governments rarely agree on the rules in the first place. The issue, experts say, is that Facebook’s audience is now so large and so diverse that it’s nearly impossible to govern every possible interaction on the site.

“This is the difference between having 100 million people and a few billion people on your platform,” Kate Klonick, an assistant professor at St. John’s University Law School and the author of an extensive legal review of social media content moderation practices, told Motherboard. “If you moderate posts 40 million times a day, the chance of one of those wrong decisions blowing up in your face is so much higher.”

Every social media company has had content moderation issues, but Facebook and YouTube are the only platforms that operate on such a large scale, and academics who study moderation say that Facebook’s realization that a failure to properly moderate content could harm its business came earlier than other platforms.

Danielle Citron, author of Hate Crimes in Cyberspace and a professor at the University of Maryland’s law school, told Motherboard that Facebook’s “oh shit” moment came in 2013, after a group called Women, Action, and the Media successfully pressured advertisers to stop working with Facebook because it allowed rape jokes and memes on its site.

“Since then, it’s become incredibly intricate behind the scenes,” she said. “The one saving grace in all of this is that they have thoughtful people working on a really hard problem.”

Facebook’s solution to this problem is immensely important for the future of global free expression, and yet the policymaking, technical and human infrastructure, and individual content decisions are largely invisible to users. In June, the special rapporteur to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a report calling for “radical transparency” in how social media companies make and enforce their rules. Many users would like the same.

Motherboard has spent the last several months examining all aspects of Facebook’s content moderation apparatus—from how the policies are created to how they are enforced and refined. We’ve spoken to the current and past architects of these policies, combed through hundreds of pages of leaked content moderation training documents and internal emails, spoken to experienced Facebook moderators, and visited Facebook’s Silicon Valley headquarters to interview more than half a dozen high-level employees and get an inside look at how Facebook makes and enforces the rules of a platform that is, to many people, the internet itself.

Facebook’s constant churn of content moderation-related problems come in many different flavors: There are failures of policy, failures of messaging, and failures to predict the darkest impulses of human nature. Compromises are made to accommodate Facebook’s business model. There are technological shortcomings, there are honest mistakes that are endlessly magnified and never forgotten, and there are also bad-faith attacks by sensationalist politicians and partisan media.

While the left and the right disagree about what should be allowed on Facebook, lots of people believe that Facebook isn’t doing a good job. Conservatives like Texas Senator Ted Cruz accuse Facebook of bias—he is still using the fact that Facebook mistakenly deleted a Chick-fil-a appreciation page in 2012 as exhibit A in his argument—while liberals were horrified at Zuckerberg’s defense of allowing Holocaust denial on the platform and the company’s slow action to ban InfoWars.

Zuckerberg has been repeatedly grilled by the media and Congress on the subject of content moderation, fake news, and disinformation campaigns, and this constant attention has led Zuckerberg and Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg to become increasingly involved. Both executives have weighed in on what action should be taken on particular pieces of content, Neil Potts, Facebook’s head of strategic response, told Motherboard. Facebook declined to give any specific examples of content it weighed in on, but The New York Times reported that Zuckerberg was involved in the recent decision to ban InfoWars.

Sandberg has asked to receive weekly briefs of the platform’s top content moderation concerns. This year, she introduced a weekly meeting in which team leads come together to discuss the best ways to deal with content-related escalations. Participants in that meeting also decide what to flag to Zuckerberg himself. Sandberg formed a team earlier this year to respond to content moderation issues in real time to get them in front of the CEO.

Zuckerberg and Sandberg “engage in a very real way to make sure that we’re landing it right and then for, you know, even tougher decisions, we bring those to Sheryl,” Potts said.

Facebook told Motherboard that last year Sandberg urged the company to expand its hate speech policies, which spurred a series of working groups that took place over six to eight months.

Sandberg has overseen the teams in charge of content moderation for years, according to former Facebook employees who worked on the content policy team. Both Zuckerberg and Sandberg declined to be interviewed for this article.

“Sheryl was the court’s highest authority for all the time I was there,” an early Facebook employee who worked on content moderation told Motherboard. “She’d check in occasionally, and she was empowered to steer this part of the ship. The goal was to not go to her because she has shit to do.”

CALMING THE CONSTANT CRISIS

Facebook’s Community Standards, which it released to the public in April, are largely the result of responding to many thousands of crises over the course of a decade, and then codifying those decisions as rules that can apply to similar situations in the future.

The hardest and most time-sensitive types of content—hate speech that falls in the grey areas of Facebook’s established policies, opportunists who pop up in the wake of mass shootings, or content the media is asking about—are “escalated” to a team called Risk and Response, which works with the policy and communications teams to make tough calls.

In recent months, for example, many women have begun sharing stories of sexual abuse, harassment, and assault on Facebook that technically violate Facebook’s rules, but that the policy team believes are important for people to be able to share. And so Risk and Response might make a call to leave up or remove one specific post, and then Facebook’s policy team will try to write new rules or tweak existing ones to make enforcement consistent across the board.

“With the MeToo Movement, you have a lot of people that are in a certain way outing other people or other men,” James Mitchell, the leader of the Risk and Response team, told Motherboard. “How do we square that with the bullying policies that we have to ensure that we’re going to take the right actions, and what is the right action?”

These sorts of decisions and conversations have happened every day for a decade. Content is likely to be “escalated” when it pertains to a breaking news event—say in the aftermath of a terrorist attack—or when it’s asked about by a journalist, a government, or a politician. Though Facebook acknowledges that the media does finds rule-breaking content that its own systems haven’t, it doesn’t think that journalists have become de-facto Facebook moderators. Facebook said many reporters have begun to ask for comment about specific pieces of content without sharing links until after their stories have been published. The company called this an unfortunate development and said it doesn’t want to shift the burden of moderation to others, but added that it believes it’s beneficial to everyone if it removes violating content as quickly as possible.

Posts that fall in grey areas are also escalated by moderators themselves, who move things up the chain until it eventually hits the Risk and Response team.

“There was basically this Word document with ‘Hitler is bad and so is not wearing pants.’”

These decisions are made with back-and-forths on email threads, or huddles done at Facebook headquarters and its offices around the world. When there isn’t a specific, codified policy to fall back on, this team will sometimes make ‘spirit of the policy’ decisions that fit the contours of other decisions the company has made. Sometimes, Facebook will launch so-called “lockdowns,” in which all meetings are scrapped to focus on one urgent content moderation issue, sometimes for weeks at a time.

“Lockdown may be, ‘Over the next two weeks, all your meetings are gonna be on this, and if you have other meetings you can figure those out in the wee hours of the morning,” Potts, who coordinates crisis response between Mitchell’s team and other parts of the company, said. “It’s one thing that I think helps us get to some of these bigger issues before they become full-blown crises.”

Potts said a wave of suicide and self-harm videos posted soon after Facebook Live launched triggered a three-month lockdown between April and June 2017, for example. During this time, Facebook created tools that allow moderators to see user comments on live video, added advanced playback speed and replay functionality, added a timestamp to user-reported content, added text transcripts to live video, and added a “heat map” of user reactions that show the times in a video viewers are engaging with it.

“We saw just a rash of self-harm, self-injury videos go online,” he said. “And we really recognized that we didn’t have a responsive process in place that could handle those, the volume. Now we’ve built some automated tools to help us better accomplish that.”

As you might imagine, ad-hoc policy creation isn’t particularly sustainable. And so Facebook has tried to become more proactive with its twice-a-month “Content Standards Forum” meetings, where new policies and changes to existing policies are developed, workshopped, and ultimately adopted.

“People assume they’ve always had some kind of plan versus, a lot of how these rules developed are from putting out fires and a rapid PR response to terrible PR disasters as they happened,” Klonick said. “There hasn’t been a moment where they’ve had a chance to be philosophical about it, and the rules really reflect that.”

These meetings are an attempt to ease the constant state of crisis by discussing specific, ongoing problems that have been surfacing on the platform and making policy decisions on them. In June, Motherboard sat in on one of these meetings, which is notable considering Facebook has generally not been very forthright in how it decides the rules its moderators are asked to enforce.

Motherboard agreed to keep the specific content decisions made in the meeting we attended off the record because they are not yet official policy, but the contours of how the meeting works can be reported. Teams from 11 offices around the world tune in via video chat or crowd into the room. In the meetings, one specific “working group” made up of some of Facebook’s policy experts will present a “heads up,” which is a proposed policy change. These specific rules are workshopped over the course of weeks or months, and Facebook usually consults outside groups—nonprofits, academics, and advocacy groups—before deciding on a final policy, but Facebook’s employees are the ones who write it.

“I can’t think of any situation in which an outside group has actually dealt with the writing of any policy,” Peter Stern, who manages Facebook’s relationships with these groups, said. “That’s our work.”

In one meeting that Motherboard did not attend but was described to us by Monika Bickert, Facebook’s head of global policy management and the person who started these meetings, an employee discussed how to handle non-explicit eating disorder admissions posted by users, for example. A heads-up may originate from one of Facebook’s own teams, or can come from an external partner.

For all the flak that Facebook gets about its content moderation, the people who are actually working on policy every day very clearly stress about getting the specifics right, and the company has had some successes. For example, its revenge porn policy and recently created software tool—which asks people to preemptively upload nude photos of themselves so that they can be used to block anyone from uploading that photo in the future—was widely mocked. But groups that fight against revenge porn say that preemptively blocking these photos is far better than deleting them after the fact, and some security experts believe the system the company has devised is safe.

Facebook says its AI tools—many of which are trained with data from its human moderation team—detect nearly 100 percent of spam, and that 99.5 percent of terrorist-related removals, 98.5 percent of fake accounts, 96 percent of adult nudity and sexual activity, and 86 percent of graphic violence-related removals are detected by AI, not users.

By Facebook’s metrics, for every instance of the company mistakenly deleting (or leaving up) something it shouldn’t, there are more than a hundred damaging posts that were properly moderated that are invisible to the user.

While Facebook’s AI has been very successful at identifying spam and nudity, the nuance of human language, cultural contexts, and widespread disagreements about what constitute “hate speech” make it a far more challenging problem. Facebook’s AI detects just 38 percent of the hate speech-related posts it ultimately removes, and at the moment it doesn’t have enough training data for the AI to be very effective outside of English and Portuguese.

Facebook has gotten significantly better at moderating over the years, but there’s simply no perfect solution, save for eliminating user-generated content altogether—which would likely mean shutting down Facebook.

“The really easy answer is outrage, and that reaction is so useless,” Klonick said. “The other easy thing is to create an evil corporate narrative, and that is also not right. I’m not letting them off the hook, but these are mind-bending problems and I think sometimes they don’t get enough credit for how hard these problems are.”

RESOLVING HUMAN NATURE

The thing that makes Facebook’s problem so difficult is its gargantuan size. It doesn’t just have to decide “where the line is” for content, it has to clearly communicate the line to moderators around the world, and defend that line to its two billion users. And without those users creating content to keep Facebook interesting, it would die.

Size is the one thing Facebook isn’t willing to give up. And so Facebook’s content moderation team has been given a Sisyphean task: Fix the mess Facebook’s worldview and business model has created, without changing the worldview or business model itself.

“Making their stock-and-trade in soliciting unvetted, god-knows-what content from literally anyone on earth, with whatever agendas, ideological bents, political goals and trying to make that sustainable—it’s actually almost ridiculous when you think about it that way,” Roberts, the UCLA professor, told Motherboard. “What they’re trying to do is to resolve human nature fundamentally.”

In that sense, Facebook’s content moderation policies are and have always been guided by a sense of pragmatism. Reviewing and classifying the speech of billions of people is seen internally as a logistics problem that is only viable if streamlined and standardized across the globe.

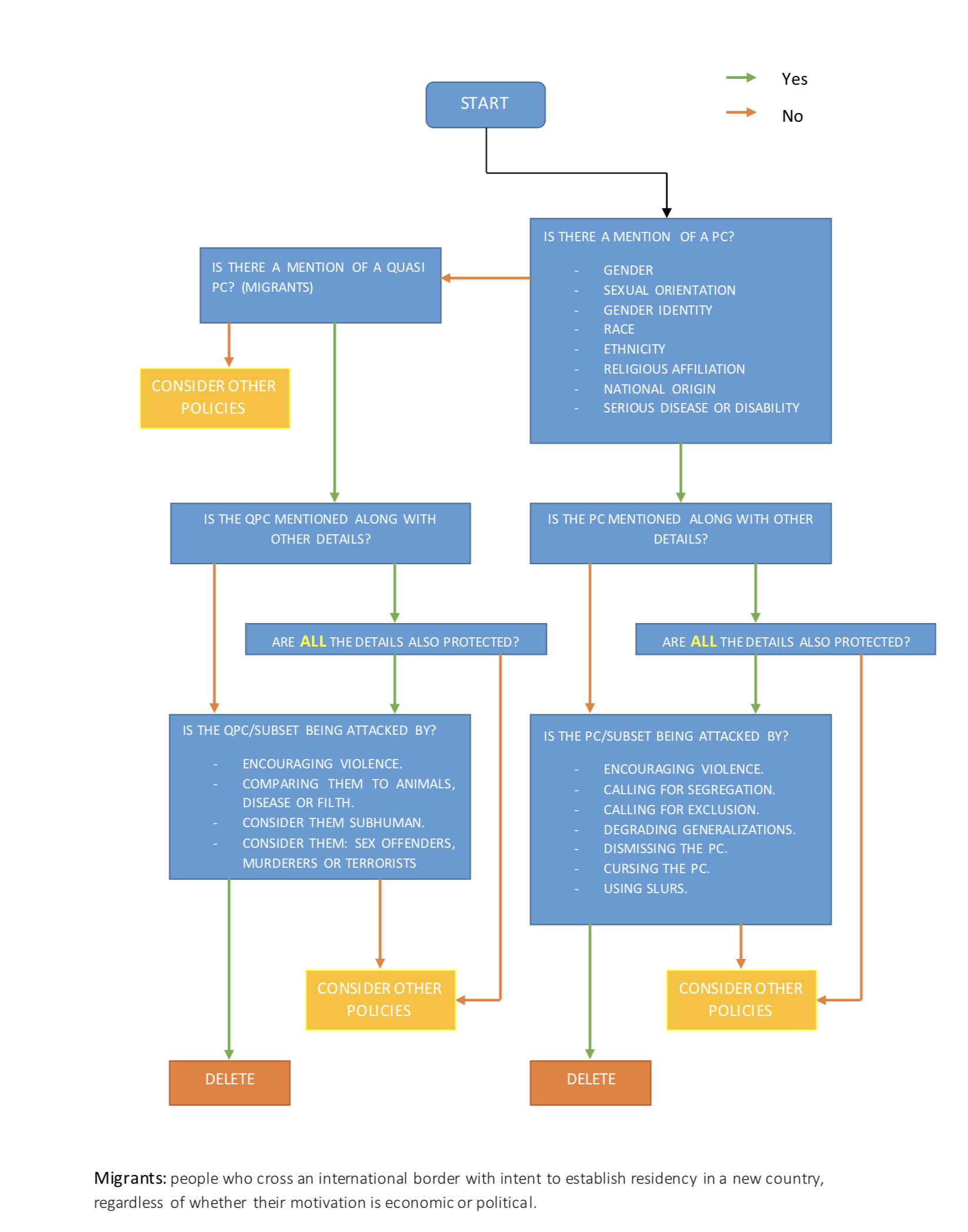

Facebook decided a decade ago that the rules it gives moderators should be objective as often as possible. What’s “objective,” of course, is core to the debate over Facebook’s content control. As Motherboard learned, Facebook’s goal for objective moderation is to have a set of rules covering every conceivable human utterance or expression on the site to eliminate potential for error from moderators. That means content should be able to flow through a series of yes-or-no or multiple choice questions; the answers to those questions will determine whether or not a post is removed.

“One of the ways that we can take bias out of the equation is by saying, we’re not asking reviewers to determine whether or not they think something is hateful, where you might have a very different decision from a reviewer in California, versus a reviewer in Dublin,” Bickert, who leads the policy team, told Motherboard. “Instead, we are saying, ‘Here is the objective criteria, if it meets this criteria, and it ticks these boxes, remove it.’ That’s how we achieve consistency.”

A top-down approach that attempts to remove human judgment from the people actually doing the moderating is a vastly different model than used by countless internet forums and Facebook’s predecessors, in which administrators or executives take broad ethical stances and then rely on moderators to exercise their own judgment about the specifics. In 2009, for example, MySpace banned content that denied the Holocaust and gave its moderators wide latitude to delete it, noting that it was an “easy” call under its hate speech policies, which prohibited content that targeted a group of people with the intention of making them “feel bad.”

In contrast, Facebook’s mission has led it down the difficult road of trying to connect the entire world, which it believes necessitates allowing as much speech as possible in hopes of fostering global conversation and cooperation. In an open letter to Facebook users last year, Zuckerberg wrote that he sees Facebook as a model for human interaction on a global scale, and envisions Facebook moving toward a “democratic” content moderation policy that can serve as a model for how “collective decision-making may work in other aspects of the global community.”

“Facebook stands for bringing us closer together and building a global community. When we began, this idea was not controversial,” he wrote. “My hope is that more of us will commit our energy to building the long term social infrastructure to bring humanity together.”

That letter, which was brought up to Motherboard by several Facebook employees as a foundational document for the future of content moderation on the platform, explains that the company’s “guiding philosophy for the Community Standards is to try to reflect the cultural norms of our community. When in doubt, we always favor giving people the power to share more.”

Zuckerberg made clear in his letter that he wants Facebook to move toward more nuanced and culture- and country-specific moderation guidelines, but doesn’t believe the technology is quite ready for it yet. His ultimate solution for content moderation, he wrote, is a future in which people in different countries either explicitly or through their activity on the site explain the types of content that they want to see and then Facebook’s artificial intelligence will ensure that they are only shown things that appeal to their sensibilities. He describes this as a “large-scale democratic process to determine standards with AI to enforce them.”

“The idea is to give everyone in the community options for how they would like to set the content policy for themselves. Where is your line on nudity? On violence? On graphic content? On profanity? What you decide will be your personal settings,” he wrote. “For those who don’t make a decision, the default will be whatever the majority of people in your region selected, like a referendum.”

“Content will only be taken down if it is more objectionable than the most permissive options allow,” he added. “We are committed to always doing better, even if that involves building a worldwide voting system to give you more voice and control.”

That system, though, is still far-off. It’s also far-removed from how Facebook moderated content in its past, and how it moderates content today. Facebook has begun using artificial intelligence in some countries to alert moderators to potentially violating content, but it is still and will remain for the foreseeable future a highly-regimented and labor-intensive process.

In Facebook’s early days, it tried telling moderators to simply “take down hateful content,” but that quickly became untenable, according to Dave Willner, Facebook’s first head of content policy, who is now head of community policy at Airbnb. Willner was instrumental in drafting Facebook’s first content moderation policies, many of which have been only slightly tweaked in the years since they were written.

“Originally, it was this guy named Karthi who looked at all the porn, but even from the beginning the moderation teams were fairly serious,” Willner told Motherboard. “It was a college site, and the concerns were largely taking down the dick pics, plus some spam and phishing. When I was joining the moderation team, there was a single page of prohibitions and it said take down anything that makes you feel uncomfortable. There was basically this Word document with ‘Hitler is bad and so is not wearing pants.’”

In 2009, Facebook had just 12 people moderating more than 120 million users worldwide. As Facebook exploded in countries that the company’s employees knew little about, it realized it had to formalize its rules, expand its moderation workforce, and make tough calls. This became clear in June 2009, when a paramilitary organization in Iran killed protester Neda Agha-Soltan, and a video of the murder went viral on Facebook. The company decided to leave it on the platform.

“If we’re into people sharing and making the world more connected, this is what matters,” Willner, who was Facebook’s head of content policy between 2010 and 2013, said. “That was a moment that crystallized: ‘This is the site.’ It’s not ‘I had eggs today,’ it’s the hard stuff.”

As Facebook blew up internationally, it found itself suddenly dealing with complex geopolitical situations, contexts, and histories, and having to make decisions about what it would and wouldn’t allow on the site.

“If you say, ‘Why doesn’t it say use your judgment?’ We A/B tested that,” Willner said. “If you take two moderators and compare their answers double blind, they don’t agree with each other a lot. If you can’t ensure consistency, Facebook functionally has no policy.”

“We want to have one global set of policies, so that people can interact across borders”

According to several other former early Facebook employees, the discussions inside the company at the time centered on determining and protecting Facebook’s broader ideology, mission, and ethos rather than taking specific stands on, say, hate speech, harassment, or violence. Motherboard granted these former employees anonymity because they expressed concern about professional repercussions.

“Facebook would tend to take a much more philosophical/rational approach to these kinds of questions, less humanistic/emotional,” one former employee told Motherboard. “Engineering mindset tended to prevail, zooming out from strong feelings about special cases, trying to come up with general, abstract, systems-level solutions. Of course, the employees are all people too. But the point is that the company tries to solve things at a systems-scale.”

A lot of these solutions were simply practical: If Facebook was going to expand into places where English was not the dominant language, it would have to hire moderators who spoke the local language. Facebook believes that global rules that jump borders are not only easier to message to its users and to enforce, but it also sees itself, according to its public rules, as a “community that transcends regions, cultures, and languages.”

Facebook understands that there are cultural and historical nuances in different countries, but still fundamentally sees the internet—and itself—as a borderless platform.

“We want to have one global set of policies, so that people can interact across borders. Part of the magic of this online community is that it is very international,” Bickert said. “We know that not everybody, in every country around the world, or every culture around the world is going to agree with everywhere we’ve drawn the line, so what we can do is, first of all, listen to what people are telling us about where that line should be. And then, just be very transparent and open about where it is.”

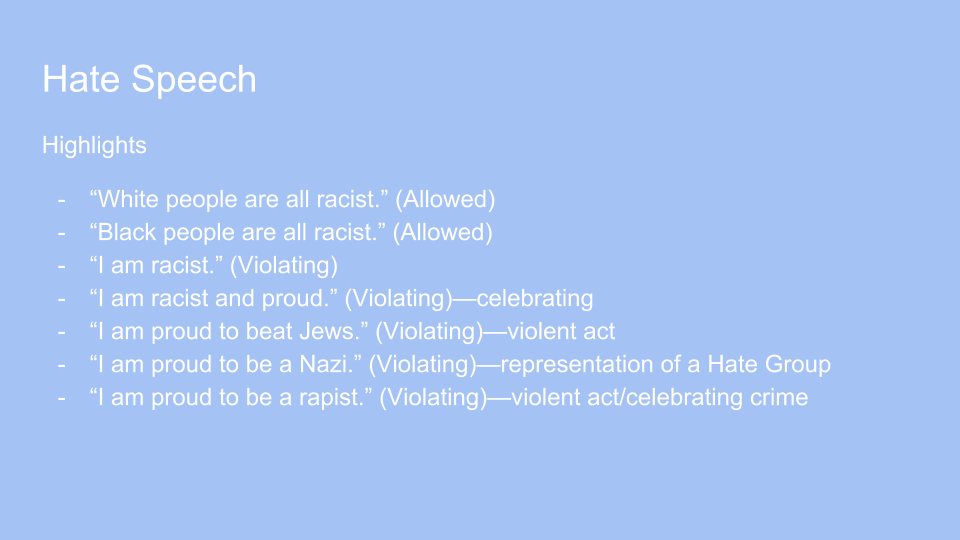

To be clear, Facebook’s publicly published community standards don’t include the exact contours of those lines. They don’t always say what words, symbols, signifiers, or images push a post from “acceptable” to something that should be deleted. And they don’t say how many or what percentage of posts have to violate the company’s standards before moderators should delete a profile or page, as opposed to just the offending posts. Leaked documents obtained by Motherboard, do, however.

The early decision to globalize Facebook’s content moderation policies, and to skew toward allowing as much speech as possible, have extended to today’s policies and enforcement, with much higher stakes.

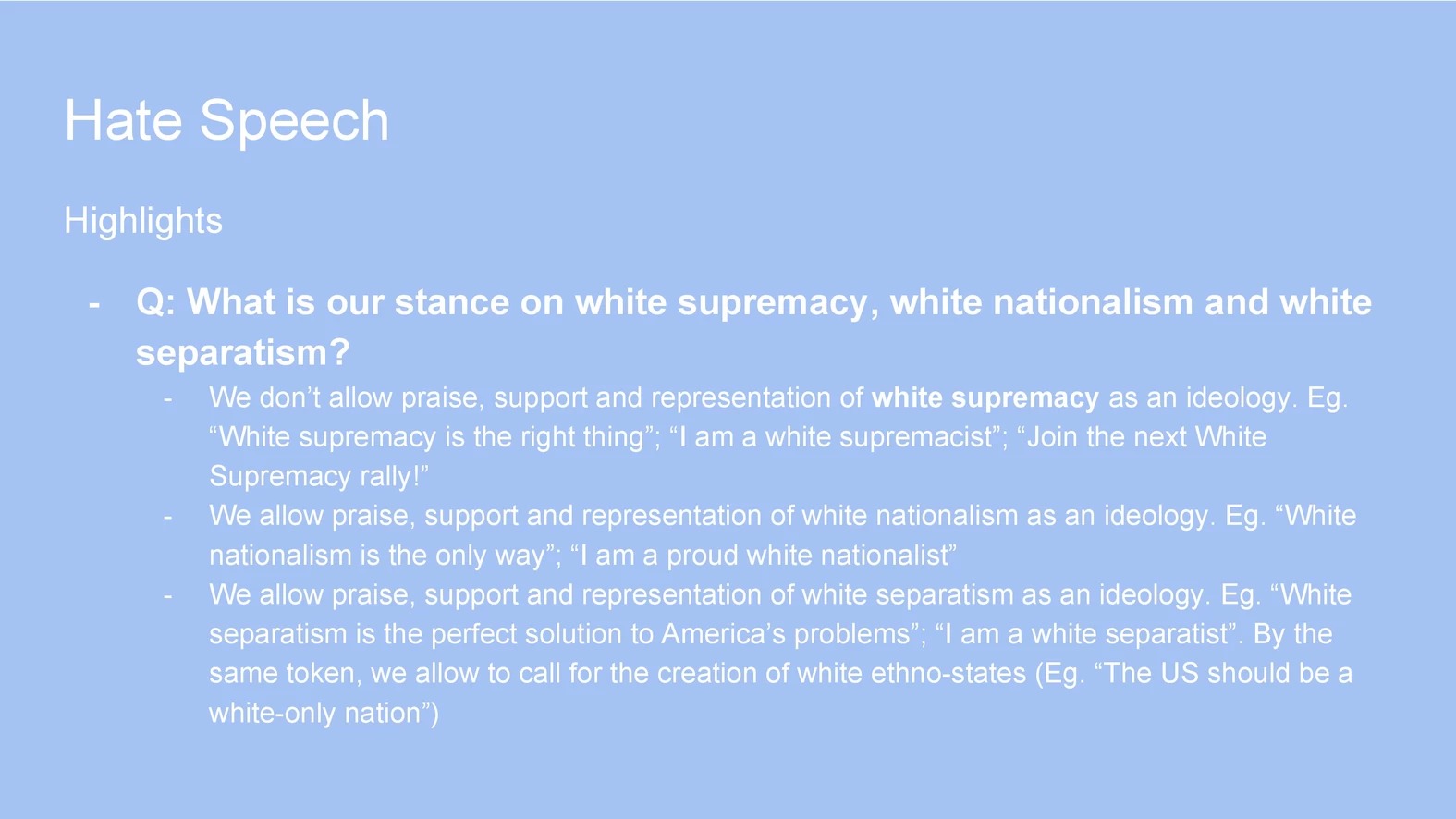

For example, Facebook bans “racism,” and specifically bans white supremacy. But according to some of the leaked documents, it has decided that it will allow white nationalism and white separatism, which Black history scholars say is indistinguishable and inseparable from white supremacy.

In the slides, Facebook defines white nationalism as ideology that “seeks to develop and maintain a white national identity,” which is a definition cribbed from Wikipedia. Facebook’s slides then note that this can be “inclusive,” in that it “includes” white people; race is a “protected characteristic” on Facebook regardless of which race it is. “White nationalism and calling for an exclusively white state is not a violation for our policy unless it explicitly excludes other [protected characteristics],” the slides say.

“During the Jim Crow era, white supremacists projected themselves as white separatists in order to make a case that they were good people,” Ibram X Kendi, who won a National Book Award in 2016 for Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, told Motherboard. “I think Facebook is taking them at their word because it puts them in the best position to project themselves as somehow concerned with the rhetoric of white supremacists. But when they split hairs, they’re able to simultaneously be social justice-oriented and in their mind defend the free speech of ‘white nationalists.’”

It’s hard to see how a moderator can be expected to interpret a policy that says advocating for a white-only United States isn’t inherently exclusionary, let alone apply it to real-world content. In multiple conversations, Facebook has yet to explain the decision in a way that makes sense when considering the historical subjugation of Black people in the United States. We were told that the company believes it has to consider how a policy that bans all nationalist movements related to race or ethnic group would affect people globally.

“We don’t just think about one particular group engaging in a certain speech, we think about, ‘What if different groups engaged in that same sort of speech?’ If they did, would we want to have a policy that prevented them from doing so?” Bickert said. “And so, where we’ve drawn the line right now is, where there is hate, where there is dismissing of other groups or saying that they are inferior, that sort of content, we would take down, and we would take it down from everybody.”

A Facebook spokesperson later explained that the current policies are written to protect other separatist movements: “Think about, and you may still not agree with the policy, but think about the groups, like, Black separatist groups, and the Zionist movement, and the Basque movement,” a Facebook spokesperson told us. Facebook added that nationalist and separatist groups in general may be advocating for something but not necessarily indicating the inferiority of others.

It’s a recurring theme for Facebook’s content policies: If you take a single case, and then think of how many more like it exist across the globe in countries that Facebook has even less historical context for, simple rules have higher and higher chances of unwanted outcomes.

“Imagine an entire policy around a small tribal group that is harassed in some tiny area of Cameroon,” Klonick said. Facebook’s power and reach means the decisions about what to do about this type of speech has been centralized by an American company. “How do you get someone to weigh in on that?”

Facebook’s policy, product, and operations teams discuss the potential tradeoffs and impacts of every policy, and multiple employees told Motherboard that there are regularly internal disagreements about the specifics of various rules.

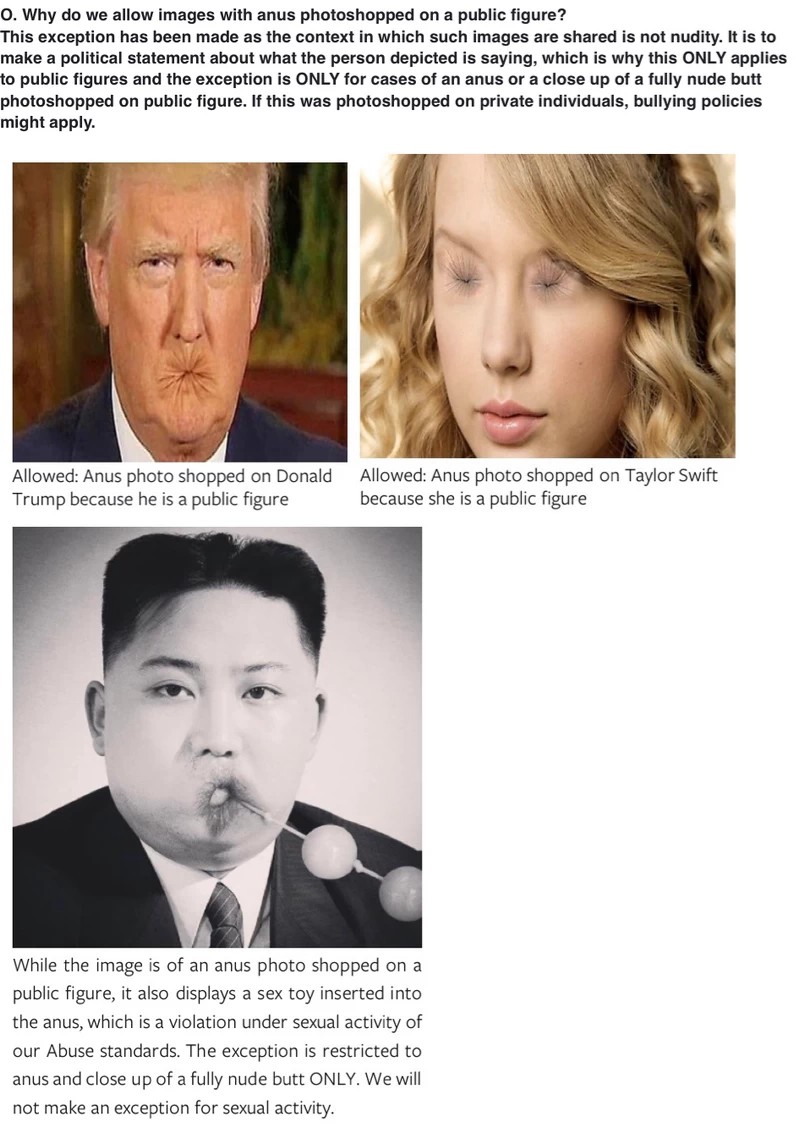

A training questionnaire offers some examples: A photo of Taylor Swift with anus eyes: OK. A photo of Donald Trump with an anus mouth: OK. A photo of Kim Jong Un with an anus mouth and anal beads being removed from it: Not OK.

“I have found it to be the case that people, once a decision is made, people will commit to that decision and try to go out and carry it out,” Potts said. “Disagreements about an attack, disagreements about a strategy, but once a decision is made you have to buy into it, and go forward.”

The slides viewed by Motherboard show over and over again that, though Facebook believes in a borderless world, the reality is that enforcement is often country-specific. This is to comply with local law and to avoid being kicked out of individual markets. Bickert told Motherboard that Facebook sometimes creates country-specific slides to give moderators “local context.” And, as Zuckerberg wrote in his letter, Facebook believes that eventually it will have to have culture- and country-specific enforcement.

“We have a global policy, but we want to be mindful of how speech that violates that policy manifests itself in a certain location versus others,” she said, adding that Facebook continues to have ongoing policy conversations about hate speech and hate organizations. “We’re constantly looking at how do we refine [policies], or add nuance, or change them as circumstances change.”

In India and Pakistan, moderators are told to escalate potentially illegal content, such as the phrase “fuck Allah” or depictions of Mohammed, to Facebook’s International Compliance unit, according to leaked documents. “No specificity required,” and “Humor is not allowed,” the documents add, referring to defamation of any religion. These sort of exceptions can apply to “content [that] doesn’t violate Facebook policy,” one document reads.

The reason is scale: ”to avoid getting blocked in any region,” the document adds.

Nine countries actively pursue issues around Holocaust denial with Facebook, including France, Germany, Austria, Israel and Slovakia, according to a leaked Facebook document. To comply with local laws, Facebook blocks users with IP addresses from those countries from viewing flagged Holocaust denial content. Facebook respects local laws “when the government actively pursues their enforcement,” the document adds.

Holocaust denial has been an issue firing up Facebook workers for years, and resurfaced again when Zuckerberg defended allowing it on the platform to Recode. In 2009, when TechCrunch did a series of articles about Facebook allowing Holocaust denial, a number of Jewish employees made public and internal arguments that it was not Facebook’s place to police that sort of content, even though they naturally found it personally offensive. A former early Facebook employee corroborated TechCrunch’s reporting to Motherboard, and said that an engineering mindset overrode those emotions, in an attempt to conjure more general and abstract solutions, rather than focusing on particular cases—arguably a sign of the moderation strategy to come.

That same year, after a shooting at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, Facebook explained that “just being offensive or objectionable doesn’t get [content] taken off Facebook.” Even today, Facebook says its “mission is all about embracing diverse views. We err on the side of allowing content, even when some find it objectionable.”

AN INDUSTRIAL PROCESS

Facebook’s content moderation policy team talks often about “drawing lines,” and then communicating those lines clearly. But, again, Facebook’s scale and chosen strategy of creating distinct policies for thousands of different types of content makes explaining them to the public—and to moderators—extremely difficult. Willner, Facebook’s first head of content policy, called this “industrialized decision making.”

“There’s 100,000 lines in the sand we just can’t see,” Roberts, the UCLA professor, said. “Versus building a different kind of system where there are really strongly voiced and pervasive values at a top-down kind of level that are imbued throughout the platform, its policies, and functionality.”

To create yes-or-no policies for everything, Facebook already tries to know exactly the parameters of what it allows on its platform, down to a necessarily pedantic level. This includes explaining which attacks qualify as hate speech on its platform, which do not, or even which sort of anuses photoshopped onto faces Facebook is willing to allow on its site. (If it’s a public figure, it’s generally allowed. A training questionnaire offers some examples: A photo of Taylor Swift with anus eyes: OK. A photo of Donald Trump with an anus mouth: OK. A photo of Kim Jong Un with an anus mouth and anal beads being removed from it: Not OK. “The exception is restricted to anus and close-up of a fully nude butt ONLY,” an internal Facebook document obtained by Motherboard says. “We will not make an exception for sexual activity.”)

“They want moderation to be so granular to basically make it idiotproof,” Marcus (name changed), who works in content moderation for Facebook, told Motherboard. Motherboard granted a number of moderation sources, who are not authorized to communicate with the press, anonymity to speak candidly about their work.

Moderators are typically not experts in any one field, so Facebook provides them with formulas to follow. But trying to encapsulate something as messy as the whole spectrum of human communication into a neat series of instructions for moderators is an ever-moving target.

“It is extremely hard or impossible to create a written policy that captures all this,” another Facebook moderation source said, referring to combating hate speech in particular.

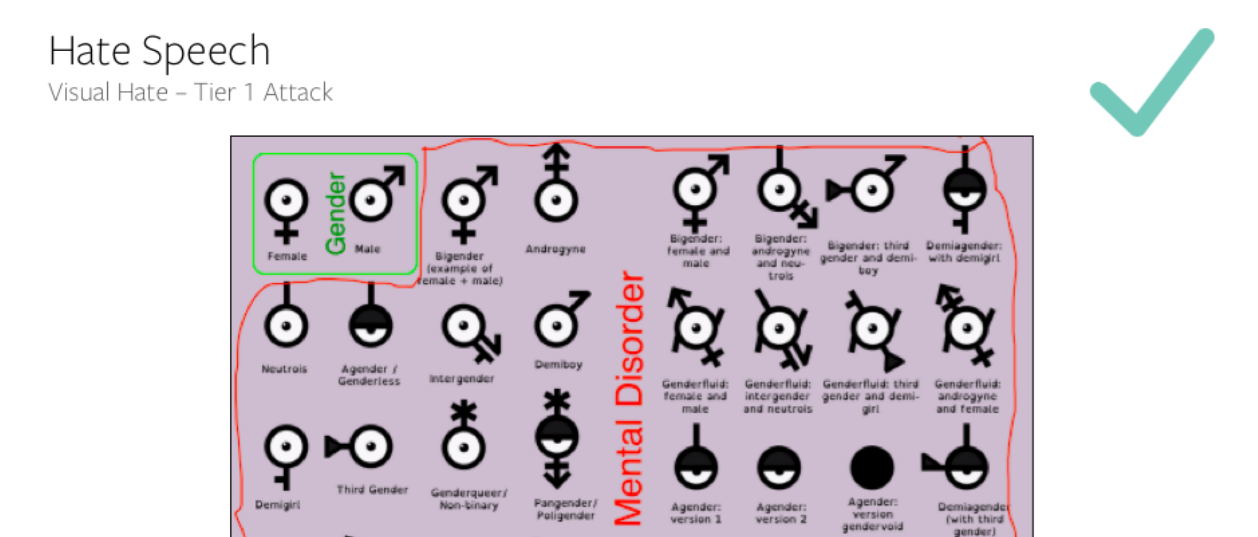

Facebook’s attempt to encompass all content in a very narrow approach ironically often leads to the platform overlooking material that by any other metric would have already been booted from the site. One leaked training manual includes an illustration with the symbols for male and female in one corner, labelled “gender,” and then a host of other genders and identities, such as genderfluid and transgender, described as “mental disorder[s].” This would, at the time of the May-dated training manual, be allowed to stay on Facebook because there is no person in the image itself being depicted, the training material says.

Facebook has seemingly realized how misplaced allowing this image and other similar ones are. According to an internal email obtained by Motherboard, moderators were recently told to ban the image as part of the “statements of inferiority” section of Facebook’s hate speech policy.

In another example, a post shows a caricature of a Jewish man with the Twin Towers on fire in the background. The Jewish man, his nose and other features exaggerated, says “Hello my dear slaves, do you remember that day when we JEWS put Thermite and bombs in those towers and demolished them,” before adding that Jewish people broadcast the news on Western media outlets, playing to the stereotype of Jews owning much of the media.

This depiction of Jews does not violate any of Facebook’s policies, and would be ignored and left on the site. This is because the Facebook-described “greedy Jew cartoon” does not qualify as hate speech without an additional attack, the training materials read. (The slide also says “Ignore because: conspiracy theory.” Facebook has publicly said that merely being wrong, in the style of some of the content of InfoWars or other conspiracy peddlers, is not enough by itself to be banned or for mods to remove material; a violation, such as pushing hate speech, is required.)

Facebook confirmed to Motherboard that without any additional context (such as a more explicit attack in the caption of the photo), this image would still be allowed because it believes it is not an attack and it does not mock the victims of 9/11. It added that it regularly removes this particular caricature if it’s accompanied by an attack (which it defines, for example, as something like “Jews are greedy.”) Facebook says it believes it’s important to not ban the caricature outright because the company says it often sees the image alongside political speech that it doesn’t want to delete.

Facebook said Sandberg has encouraged the company to keep thinking about how to use a more granular approach, while drafting hate speech policies and while enforcing them. In one change that emerged after Sandberg encouraged more work on dealing with hate speech, Facebook now protects “women drivers” against direct attack and removes related content. Previously, attacks on “women” were banned but attacks on “women drivers” were not, because Facebook did not consider “drivers” a protected group.

“There’s always a balance between: do we add this exception, this nuance, this regional trade-off, and maybe incur lower accuracy and more errors,” Guy Rosen, VP of product management at Facebook, said. “[Or] do we keep it simple, but maybe not quite as nuanced in some of the edge cases? Balance that’s really hard to strike at the end of the day.”

“What many of these firms fear is that their primary business could very easily shift to just being the security forces of the internet, 24/7”

The process of refining policies to reflect humans organically developing memes or slurs may never end. Facebook is constantly updating its internal moderation guidelines, and has pushed some—but not all—of those changes to its public rules. Whenever Facebook identifies one edge case and adds extra caveats to its internal moderation guidelines, another new one appears and slips through the net.

One hate speech presentation obtained by Motherboard has a list of all the recent changes to the slide deck, including additions, removals, and clarifications of certain topics. In some months, Facebook pushed changes to the hate speech training document several times within a window of just a few days. In all, Facebook tweaked the material over 20 times in a five month period. Some policy changes are slight enough to not require any sort of retraining, but other, more nuanced changes need moderators to be retrained on that point. Some individual presentations obtained by Motherboard stretch into the hundreds of slides, stepping through examples and bullet points on why particular pieces of content should be removed.

INSIDE THE GLASS BOX

Marcus likened moderating content at Facebook to sitting inside a glass box, separated from the context and events that are happening outside it. Moderators go into their office, follow binary and flow-charted enforcement policies for hours on end, sometimes with colleagues having little idea of the nuance of the material they’re analyzing, then go home. It’s not like watching the news, or staying informed, Marcus said.

“There’s a collapse of the context with which we see the world, or use to interpret this content,” he added. “We should be the experts, and instead are in this false construction. It’s not a reflection of the real world basically.”

When a Facebook user flags a piece of content because they believe it is offensive or a violation of the site’s terms of use, the report is sent to a moderator to act upon. The moderator may decide to leave the content online, delete it, or escalate the issue to a second Facebook team member who may have more specialist knowledge on a particular type of content. Facebook may push the piece of content higher up the chain too, for a third review. But moderators don’t only have to decide whether to delete or ignore, they have to select the correct reason for doing so—reasons that can often overlap. Does the content violate the site’s nudity or revenge porn policy? Is this hate speech or a slur?

“We could spend many days arguing over which reason we would delete ‘you can’t trust Ivanka, she sleeps with a dirty k***,’” even though k*** is a slur and a reason to delete the post no matter what,” Marcus said, referring to Ivanka Trump and her Jewish husband Jared Kushner. Marcus said this sort of problem exists, to a certain extent, with all of the policies. But the list of options for hate speech is much longer, and with possibilities that are hard to differentiate from one another, meaning it can be much more difficult for moderators to pick the “correct” answer that matches that of their auditor.

“This is often a nonsensical exercise,” Marcus added.

Facebook requires this decision data, however, to make sure content is being removed for the right reason—if there is a sudden spike in posts that are deleted as hate speech, rather than, say, celebrating crime, Facebook is going to have a better idea of what exactly is on its platform. It will also be able to quantify whether it is effectively stopping that content from spreading. (Facebook keeps track of how often offending content is viewed and engaged with, and how quickly it is deleted.) Startlingly, Facebook only started collecting data on why moderators delete content in 2017, Rosen told Motherboard.

“We didn’t even have a record, because we were optimizing just to do the job. We didn’t actually have a record of what it was deleted for,” he said. “There isn’t really a playbook for this. No one’s done it at this kind of scale, and so, we’ve developed, and we are developing metrics that we think represent the progress that we can make.”

“We still don’t know if [language processing in Burmese] is really going to work out, due to the language challenges”

If the reported content contains multiple violations—as it often will, with speech being as complicated as it is—then moderators have to follow a hierarchy that explains which policy to delete the content under, a second moderator explained. One of the sources said that this can slow down the removal process, as workers spend time trying to figure out the exact reason why the content should be deleted.

“It can be confusing learning the hate speech policy,” a third moderation source told Motherboard. “Moderators constantly will ask one another on most hate speech jobs on how they read it,” they added.

Brian Doegen, Facebook’s global head of community operations, who oversees moderator training best practices, said Facebook is introducing a “simulation” mode for its moderators, so they can practice removing content without impacting Facebook’s users’ content, and then receive more personalized coaching. Doegen pointed to hate speech specifically as an example where more coaching is often necessary.

Facebook also collects moderator data so this binary approach can be more easily automated, whether that’s Facebook applying streams of logic—if a human says the image contains X, Y, and Z, then automatically remove it—or continuing to develop artificial intelligence solutions that can flag content without user reports.

The moderation approach “creates the much better feedback loop,” Rosen said, with human conclusions providing the input for the actions the software ultimately takes.

If moderators do perform well, they are given more hate speech cases, several moderators said, because it is much harder to police than other types of content. But, because normal moderators and those dealing with hate speech are scored on the same basis, that also potentially increases hate speech mods’ chances of getting a bad score. Moderators face consequences if they fall below a 98 percent accuracy rate, Marcus added.

And they typically don’t last long in the job.

“Hardly anyone has their year anniversary,” Marcus said. “A lot of the employees just don’t care. But the ones that care fall to stress for sure.” Some people do not get burned out and just like to stay busy, moderating flagged content—or “jobs”—back to back, one of the other sources said, but acknowledged it’s “a stressful environment.”

Facebook would not share data about moderator retention, but said it acknowledges the job is difficult and that it offers ongoing training, coaching, and resiliency and counseling resources to moderators. It says that internal surveys show that pay, offering a sense of purpose and career growth opportunities, and offering schedule flexibility are most important for moderator retention.

Trainers do tell moderators to review a piece of content holistically, but due to Facebook’s moderation point scoring, “being marked correct basically reduces us all to using the most clearly defined lines as the standard,” Marcus said. When in reality, the lines of a piece of hate speech may not be so explicit.

The fact is, moderators do still need to exercise some form of their own judgment even when given paint-by-numbers steps to remove content: whether a photo contains Facebook’s definition of “cleavage,” or internally debate if a post is being sarcastic, Marcus explained.

And this is why, despite Facebook investing heavily in artificial intelligence and more automated means of content moderation, the company acknowledges that humans are here to stay.

“People will continue to be part of the equation, it’s people who report things, and the people who review things,” Rosen said.

PAINFUL MISTAKES

In October 2016, a 22-year-old Turkish man logged into Facebook and started livestreaming.

“No one believed when I said I will kill myself,” he said. “So watch this.”

He pulled out a gun and shot himself.

Just six months earlier, Facebook had rolled out Facebook Live to anyone on the platform. It didn’t anticipate the immense stress this would put on its moderation infrastructure: Moderating video is harder than moderating text (which can be easily searched) or photos (which can be banned once and then prevented from being uploaded again). Moderating video as it’s happening is even harder.

“We’re learning as we go,” Justin Osofsky, Facebook’s head of global operations, told Motherboard. “So, until you release live video, you don’t fully understand the complexity of what it means to create the right policies for live video, to enforce them accurately, and to create the right experiences. But you learn. And we learned, and have improved.”

Facebook’s early decisions to connect as many people as possible and figure out the specifics later continue to have ramifications. The company believes that its service is a net positive for the countries it enters, even if the company itself isn’t fully prepared to deal with the unexpected challenges that come up in newer territories. For every person who has a negative experience on the platform as a result of content moderation shortcomings—which can range from seeing a naked person or spam in their feed to something as extreme as a person killing themselves on Facebook Live—there are millions of people who were able to reconnect with old classmates, promote their small business, or find an apartment.

“I feel an immense responsibility to ensure that people are having a safe, good experience on Facebook”

And so Facebook continued to push into new territories, and it is still struggling with content moderation in some of them. Earlier this year, Facebook was blamed for helping to facilitate genocide in Myanmar because it has allowed rumors and hate speech to proliferate on the platform. As Reuters reported, this is in part because, until recently, Facebook had few moderators who spoke Burmese. Rosen, Facebook’s head of product, told Motherboard the company’s hate speech-detecting AI hasn’t yet figured out Burmese, which, because of Myanmar’s isolation, is encoded by computers differently than other languages. Facebook launched in Myanmar in 2011.

“We still don’t know if it’s really going to work out, due to the language challenges,” Rosen said. “Burmese wasn’t in Unicode for a long time, and so they developed their own local font, as they opened up, that is not compatible with Unicode. … We’re working with local civil society to get their help flagging problematic content posts, and, current events also, so that we can go and take them down, but also understanding how we can advance, especially given our app is extremely popular, the state of Unicode in the country.”

Osofsky says that his team, Bickert’s policy team, and the product team often does “incident reviews” in which they debrief on “painful mistakes” that were made in policy moderation and to determine how they can do better next time.

“Was our policy wrong or right? If our policy was ok, was the mistake in how we enforced the policy?” Osofsky said. “Was the mistake due to people making mistakes, like reviewers getting it wrong, or was it due to the tools not being good enough, they couldn’t surface it?”

Everyone Motherboard spoke to at Facebook has internalized the fact that perfection is impossible, and that the job can often be heartbreaking.

“I feel an immense responsibility to ensure that people are having a safe, good experience on Facebook,” Osofsky said. “And then, when you look into mistakes we’ve made, whether it’s showing an image that violates our policies and should have been taken down, whether it’s not responding sensitively enough in an intimate moment … these are moments that really matter to people’s lives, and I think I and my team feel a responsibility to get it right every time. And when you don’t, it is painful to reflect on why, and then to fix it.”

The people inside Facebook’s everything machine will never be able to predict the “everything” that their fellow humans will put inside it. But the intractable problem is Facebook itself: If the mission remains to connect “everyone,” then Facebook will never solve its content moderation problem.

Facebook’s public relations fires are a symptom, then, of an infrastructural nightmare that threatens an ever-increasing swath of humanity’s public expression. For Facebook, it is a problem that could consume the company itself.

“What many of these firms fear is that their primary business could very easily shift to just being the security forces of the internet, 24/7,” Roberts, the UCLA professor, said. “That could be all Facebook really does.”

And that’s why, though the people who were invited to Mark Zuckerberg’s house to talk about content moderation appreciated the gesture, many of them left feeling as though it was an act of self-preservation, not a genuine attempt to change Facebook’s goal of making one, global community on the platform. (Facebook confirmed that the dinners happened, and said that Rosen and Bickert were also in attendance to share the feedback with the product and policy teams.)

Everyone in the academic world knows that Zuckerberg is talking to professors about the topic, but he hasn’t made clear that he’s actually doing anything with those conversations other than signaling that he’s talking to the right people.

“Everyone I’ve talked to who comes out of it said ‘I don’t really think he was listening,’” a person familiar with the dinners told Motherboard. “It feels like by inviting all these people in, they’re trying to drive the problem away from them.”

Got a tip? You can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.