The biggest extinction event in planetary history was driven by the rapid acidification of our oceans, a new study concludes. So much carbon was released into the atmosphere, and the oceans absorbed so much of it so quickly, that marine life simply died off, from the bottom of the food chain up.

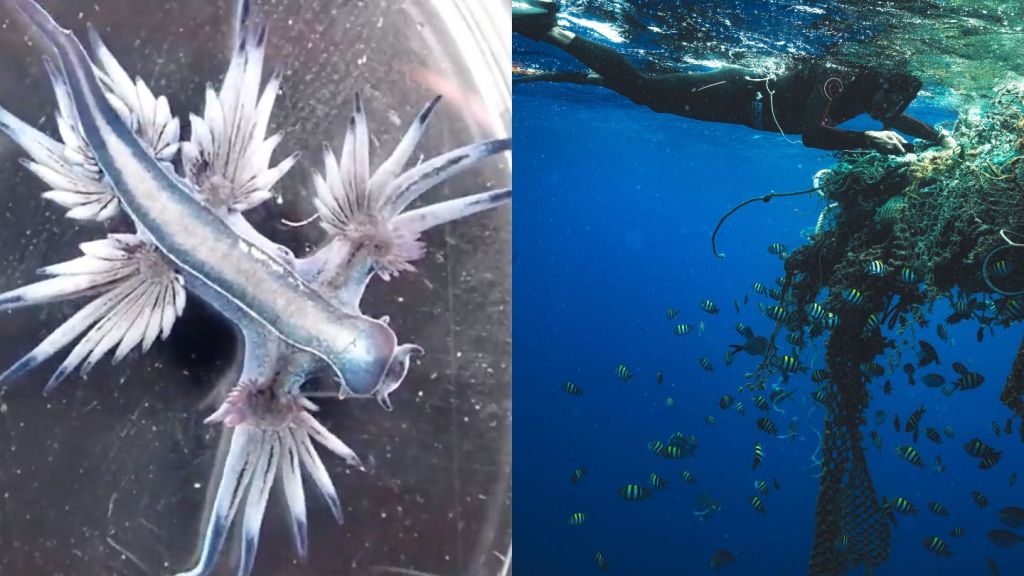

That doesn’t bode well for the present, given the disturbingly similar rate that our seas are acidifying right now. Parts of the Pacific, for instance, are already so acidic that sea snails’ shells begin dissolving as soon as they’re born.

Videos by VICE

The biggest die-off in history, the Permian Extinction event, aka the Great Dying, extinguished over 90 percent of the planet’s species—and 96 percent of marine species. A lot of theories have been put forward about why and how, exactly, the vast majority of Earth life went belly up 252 million years ago, but the new study, published in Science, offers some compelling evidence acidification was a key driver.

A team led by University of Edinburgh researchers collected rocks in the United Arab Emirates that were on the seafloor hundreds of millions of years ago, and used the boron isotopes found within to model the changing levels of acidification in our prehistoric oceans. Through this “combined geochemical, geological, and modeling approach,” the scientists say, they were able to accurately model the series of “perturbations” that unfolded in the era.

They now believe that a series of gigantic volcanic eruptions in the Siberian Trap spewed a great fountain of carbon into the atmosphere over a period of tens of thousands of years. This was the first phase of the extinction event, in which terrestrial life began to die out.

The study explains that the second phase of the event happened much more quickly. “During the second extinction pulse, however, a rapid and large injection of carbon caused an abrupt acidification event that drove the preferential loss of heavily calcified marine biota,” the authors write.

So does this study mean we should be especially worried about the phenomenon taking hold today?

“Yes,” said Dr. Rachel Wood, a professor of carbonate geoscience at the University of Edinburgh and one of the paper’s authors.

“We are concerned about modern ocean acidification,” she told me in an email. “Although the amount of carbon added to the atmosphere that triggered the mass extinction was probably greater than today’s fossil fuel reserves, the rate at which the carbon was released was at a rate similar to modern emissions.”

In other words, the Siberian Traps probably spewed out more carbon in total, but we’re spewing out just as fast. And that’s overwhelming the planetary equilibrium.

“This fast rate of release was a critical factor driving ocean acidification,” Wood said.

Why?

“The rate of release is critical because the oceans absorb a lot of the carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, around 30 percent of the carbon dioxide released by humans,” Wood said. “To achieve chemical equilibrium, some of this CO2 reacts with the water to form carbonic acid. Some of these molecules react with a water molecule to give a bicarbonate ion and a hydronium ion, thus increasing ocean ‘acidity’ (H+ ion concentration).”

Marine animals whose skeletons are comprised of calcium carbonate—and that’s a lot of them (think snails, coral), which form a crucial part of the food chain—dissolved or couldn’t form in the first place. And that is what’s happening today.

“Between 1751 and 1994, surface ocean pH is estimated to have decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14, representing an increase of almost 30 percent in H+ ion concentration in the world’s oceans,” Wood said.

That’s a major uptick in ocean acidity in a relatively short amount of time, and it’s happening because humans have burned fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas with reckless abandon since the Industrial Revolution. That’s fueling climate change, of course, as well as its less-discussed, but potentially equally cataclysmic sibling, ocean acidification.

“Scientists have long suspected that an ocean acidification event occurred during the greatest mass extinction of all time, but direct evidence has been lacking until now,” study coordinator Dr. Matthew Clarkson said in a statement. “This is a worrying finding, considering that we can already see an increase in ocean acidity today that is the result of human carbon emissions.”

Much of marine life is already in grave danger from acidification. It’s contributing to the bleaching of coral reefs around the world, and, as mentioned before, it’s killing sea snails in the Pacific. If it worsens, acidification could threaten the whole of the marine biosphere, and, obviously, the land-dwelling creatures that depend on it too.

In 2013, marine scientists released a “State of the Oceans” report that found that the rate of current acidification was “unprecedented.” They noted that the seas were acidifying faster than any point in the last 300 million years. That study didn’t take into account the new data, of course, but that’s the timeline we’re dealing with: The last time the oceans were so acidic was in the midst of the greatest extinction in the history of the world.

Worried about killer robots? Maybe you should be. Watch Motherboard’s documentary, Inhuman Kind.