Nearly every drug you snort, inject, smoke, butt-plug, vaporize or freebase eventually ends up back in the water supply via your excrement. The fish love it—well, maybe not the ones mutating from it. But apparently crabs and trout aren’t the only ones sifting through your waste.

Across the globe, researchers at wastewater treatment plants are testing for psychoactive substances passed by drug users through their feces and urine. The data can be incredibly valuable, letting scientists and law enforcement quickly track drug use trends and identify new substances on the market. It can also measure the impact of drug policy strategies, even highlight which days of the week drug use spikes (cocaine on the weekends, anyone?).

Videos by VICE

But with this research comes some ethical entanglements. Testing waste could help anticipate the sharp rise in carfentanil or fentanyl overdoses, for example, by detecting the drug in sewage. But the same strategies can be used to stigmatize against certain populations, and as we’ve seen with the War on Drugs in the US, this could have lasting consequences for those communities.

*

Wastewater analysis may become commonplace in the United States in a few years, because while there are challenges to getting accurate results, it’s very easy to get samples.

Traditionally, drug epidemiologists have had to rely on questionnaires, but such surveys aren’t cheap and are riddled with response biases since many drug users aren’t keen to tell the truth about breaking the law. On the other hand, you can easily measure all the fallout of drug use: HIV transmission, overdose, rehab check-ins, ER visits, death. But those infrequent incidents only happen after the fact.

Drug testing wastewater was first proposed in 2001 by Christian Daughton, a scientist from the Environmental Protection Agency hoping to raise awareness of the ecological impact drugs can have. Only around half of personal care products and pharmaceuticals are removed by treatment plants in a troubling “pee-to-food-to-pee loop.” These pharmaceutical contaminants—known as “chemicals of emerging concern”—have researchers in Seattle and Baltimore scrambling to understand their effect on wildlife.

But that’s working downstream—what about upstream?

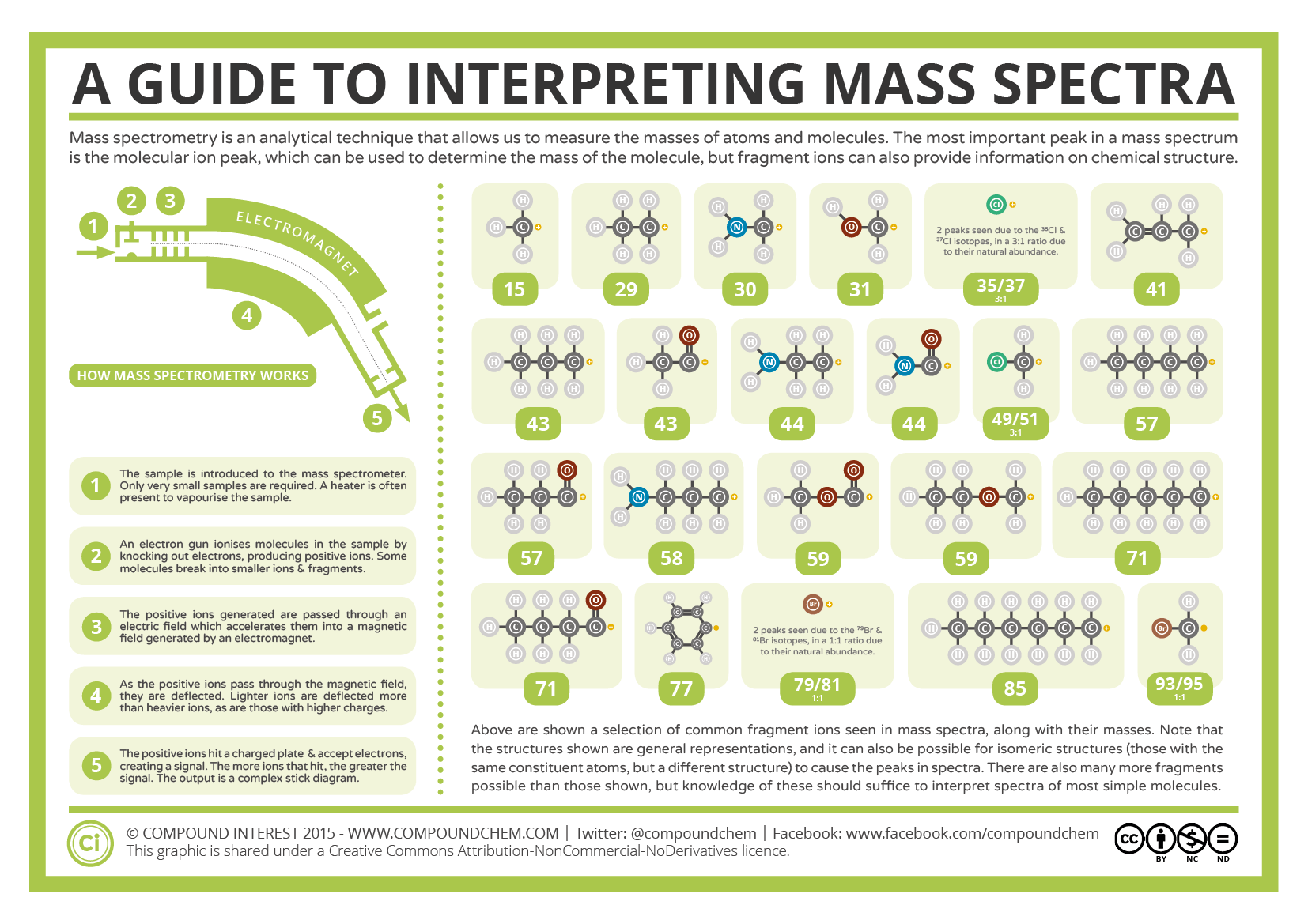

Italy in 2005 became the first country to use mass spectrometry, a tool that measures atom and molecule mass, in water samples to approximate local cocaine consumption, discovering that Italy’s longest river, the Po, “steadily carried the equivalent of about 4kg [of] cocaine per day,” equal to 40,000 daily doses.

In 2013, researchers looked at 47 WWTPs in 21 European countries, analyzing the narcotic laced ordure of nearly 25 million people. Australia, which has performed wastewater tests in the past, is spending $3.6 million to test 30 sites across the continent, monitoring not only methamphetamine use, but also alcohol. Now the idea is spreading across China, with at least five similar studies planned in the next six months. In mid-December 2016, New Zealand became the latest country to latch onto this trend and have already begun looking for traces of meth, cocaine, heroin, α-PVP (also known as “flakka”), MDMA and creatinine (a naturally-occurring human byproduct, used for a control.)

But New Zealand’s approach is somewhat unique. Researchers from the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, are also working closely with police. In most cases, this analysis is done by researchers alone—but this kind of tandem relationship may become more common.

Only a few such tests have been conducted in North America—a couple near Albany, and several in Oregon and Washington, for example—but as the practice catches on, and as drug detection technology improves, wastewater analysis is likely to become routine.

“Like so many sort of new ideas, a lot of people don’t want to be the first person on the dance floor,” said Dr. Caleb Banta-Green, a senior researcher at the University of Washington’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute. He’s been scouring wastewater for drugs in King County and elsewhere for eight years. “But there’s a point when you look pretty bad being the last person on the dance floor,” he said.

On November 16th, the National Drug Emergency Warning System (NDEWS) presented a webinar titled “Using Wastewater Testing as a Drug Epidemiology Tool” hosted by Banta-Green and Dr. Daniel Burgard, an associate chemistry professor at University of Puget Sound.

The two researchers, who have published together on the topic, were recently tapped by the federal government to monitor wastewater for levels of cannabis use before and after legalization in Washington.

“This work is probably in what I would call its adolescence. It’s not fully mature,” Banta-Green said. “We’re still learning, there’s still things to tweak and fine-tune, but I do think there is some value now in real-time [analysis.]”

That value includes results that are specific, timely and scalable in clear, often political boundaries covering most of a given population (excluding areas with septic tanks.) You can tell if a large narcotic bust had an impact, if at all, on a community’s rate of drug use, for example, and even determine if new synthetic drugs are present.

However, even wastewater testing doesn’t give a complete picture. There is often missing data, known as censoring, such as when population fluctuates. If the study doesn’t have confidence intervals or error bounds, it isn’t possible to tell if certain drug use is more prevalent in the city versus concentrated in a tourist trap, for instance, such as London. Italian researchers sampled the waste of 5.5 million Londoners in 2005—but that year, the city experienced 24.2 million overnight visits from foreigners. How can you tell which drug-infused urine comes from who?

Image: Compound Interest/Creative Commons

“You need to bring in this sort of sociology component as well to help interpret those data,” Banta-Green said. “That’s a subtly that is generally lost. It’s important in terms of communicating the results, though, to continue to frame them in the proper context.”

That context includes licit medical uses. When heroin breaks down in the body, it becomes morphine, which is often used legitimately in surgery. How do researchers tell legal morphine from illegal morphine if all that excreta mixes together? One method is also looking for exclusive metabolites of heroin, such as 6-acetylmorphine. It’s a similar situation when looking for benzoylecgonine, a cocaine metabolite, or THC-COOH and 11-OH-THC, metabolites of cannabis. These metabolites are much easier to distinguish than the unchanged chemical.

There are even lawful medical applications for methamphetamine: in an obesity drug called Desoxyn and levomethamphetamine, present in Vick’s vapor inhalers, and known to give false positives on drug tests. Nevertheless, researchers can actually detect how the methamphetamine was manufactured and determine if it is pharmaceutical or not.

“Different manufacturing processes will result in different mixtures of those [methamphetamine] compounds and some of the over-the-counter compounds have more or less of one of those,” Banta-Green said. “Those potentials of the over-the-counter or prescription medication contributions to methamphetamine, if I recall, were way under 1% … that we believe was detectable.”

So, while it may be tricky, scientists can generally tell if you got your opioids from a doctor or not. What about those exotic new psychoactive molecules constantly being introduced to the black market?

According to the United Nation’s 2016 World Drug Report, a total of 644 new drugs have been reported by 102 countries and territories between 2008 and 2015. Wastewater analysis promises to show real-time results for emerging drugs, including novel benzodiazepines, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones, opioids, phenethylamines, tryptamines, and other new substances. But finding something like a cutting-edge fentanyl analogue is incredibly complicated.

“It’s very challenging, it’s very data intensive, but there are ways to try to pull out compounds that might be in there, but you still have to sort of have a guess a little bit of what you’re looking for or the apparent structure,” Burgard said.

*

But is any of this ethical? After all, wastewater analysis is basically drug testing without consent. Should we fear a future where ordinary citizens have their toilet effluence regularly monitored?

A study in the scientific journal Addiction found there were no major ethical concerns raised when monitoring large populations’ wastewater. However, the paper’s authors did say it was necessary “to minimize possible adverse consequences in studying smaller populations, such as workers, prisoners and students.”

In other words, it’s not exactly ethical to drug test all the port-a-potties at Electric Daisy Carnival, for instance—although, this type of research is not unheard of. In 2009, a researcher analyzed wastewater at a prison in Catalonia, finding drug use was much lower compared to a nearby town. Thankfully, the prison wasn’t revealed, as that may have encouraged strict policy responses, such as restricting visitor access to reduce smuggling, a form of collective punishment.

Perhaps that’s why a few US cities, out of fear of developing the wrong reputation or attracting unwanted attention, have declined to allow wastewater sampling. If your town gets painted as the meth capitol of the county, what kind of message does that send? Analyzing the waste of poor communities could potentially perpetuate a cycle of stigma. And finally, does this research endanger individual privacy?

The ability to work upstream to find individual drug users is available to law enforcement, if they choose—for now, such a narrow focus is too costly to be worth it, not to mention, as Burgard et al. note, the “feasibility issues of thousands of point source samplers and … the legal status of sewage is unclear, including who owns it.”

In other words, installing drug monitoring filters in everyone’s pipeline isn’t worth the investment—so don’t flush your stash just yet—but that isn’t to say a future in which halfway houses or sole individuals on probation are screened is out of the question, especially as wastewater analysis becomes more routine.

In the meantime, it has been suggested police use wastewater data to “guide decisions at strategic and/or operational levels” or “assess the market share held by criminal groups.”

“The law enforcement community has capacity to do this type of work, if they wanted to, [but] that’s not what we’re doing. And we’re not intersecting with that stakeholder group on this work,” Banta-Green explained, adding that also depends on if researchers are willing to work with law enforcement in the first place. Sometimes scientists decide that they don’t want to give any more information to the police.

Even so, the real question is how this wastewater data is used. In their research, Burgard et al. defined the issue succinctly: “Perhaps the issue of ethics will come down to whether sewage-based data is used for understanding drug epidemiological trends or for handing out punishment.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.

More

From VICE

-

Rembrandt's 'Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell),' painted in 1624. -

-