This article was originally published on Noisey UK.

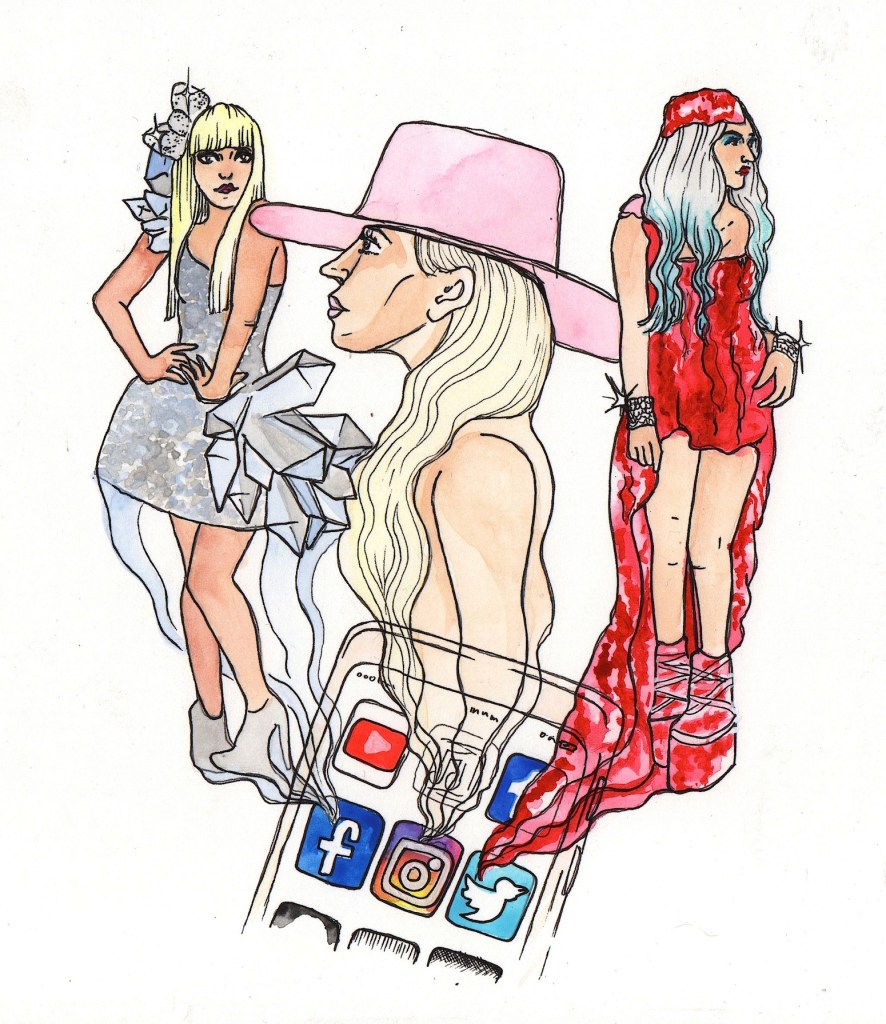

Despite having hustled, stripped and set fire to hairspray cans with her tits out in bars across New York City for years, it wasn’t until releasing her debut album in 2008 that Lady Gaga became a household name. Bewildered journalists couldn’t make sense of her platinum hair bows, tiny leotards and that purple teacup she used to carry with her wherever she went. But she was an immediate hit among pop fans, who became enthralled by her inherently flamboyant sense of style, increasingly creative music videos and refreshing determination to push boundaries in a pop arena that was actually quite cool at the time, but not particularly weird.

Videos by VICE

Although Gaga herself was undeniably eccentric, her music—particularly at the start of her career— was broadly palatable. Despite her debut being marketed as a complex Warholian exploration of fame, the tracks were catchy, repetitive and synth-driven. That said, they were also fucking massive. The pulsing synths and hypnotic chorus of “Just Dance” were the ideal accompaniment to WKD-fuelled teen house parties worldwide and the built-for-choreography beats of “Poker Face” had the ability to turn any dingy small town gay club into a euphoric, glittering stampede. Kids across the world ate up her addictive hits, avant-garde outfits and messages of acceptance, propelling her to the status of global icon in just a handful of months.

But it wasn’t until the summer of 2009 that these aforementioned kids were given a name: “Little Monsters,” which she began calling out to the crowd during her live shows. Giving a whole fandom a nickname of sorts was already commonplace in K-pop, but Gaga was the first to do it on such a grand scale in a western context—using it to describe the way fans would writhe, scream and dance in the pits of her high-octane performances. Naming her fans did two things. First, it created an “us” and “them” narrative. You were either a true Gaga fan, or you weren’t. And second, it grouped them all together in a way that made sense online. For a generation of kids who existed on the internet, being a Little Monster meant more than going to a few gigs. It meant having a support network of like-minded people from around the world that you could interact with, like an extended family. Finally, there was a name for all the people who spent their waking hours immersed in the online world of Lady Gaga; one that was getting bigger by the year.

This formation quickly created a new blueprint: Bieber fans dubbed themselves, “Beliebers”, Taylor got her “Swifties” and the “Rihanna Navy” formed. But Gaga was the first. Professor Mathieu Deflem—who wrote book Lady Gaga and the Sociology of Fame and dedicated an entire university course syllabus to her influence – agrees that Gaga’s effect on fandom culture in this way is notable: “I would say that Gaga has at least facilitated this process for other pop stars and celebrities,” he says. “Other stars now constantly name their fanbases—so much so that the effect is kind of wearing off. That also means that there is only one Lady Gaga, and that the impact of imitating her or adopting her various strategies are limited.”

Strangely, as Gaga’s fan base multiplied, her personal relationship to them tightened. It was in mid-to-late 2009—just before the re-release of her debut album, The Fame Monster—that she started using a “Monster Claw” hand symbol. It was a gesture as simple as curling her fingers and raising them in the air, but she did it so frequently online and on-stage that it swiftly caught on. Fans would put their “paws up” at concerts and she eventually got the claw tattooed on her back, which she shared on Instagram like a gift back to the fandom. She would talk about feeling like an outsider, sharing personal stories and preaching about tolerance and the importance of equality, consistently vocalising a system of beliefs that she stood for. And so, the Little Monsters had both a name, an ideology and a universal symbol to unite them. By outlining exactly what a Little Monster should be, and accelerating this sense of community among her fans, Gaga basically created a cult (but, y’know, a fun one rather than the kind that ends in something sinister like mass death). And all of this was able to snowball online.

“Gaga and her team understood the creation of a hardcore fanbase via social networking sites, and her approach to fans has always been very personal and direct,” says Deflem, explaining how and why the Little Monsters ultimately thrived on the internet. “She established a culture where it seems there’s a symmetry between her and her fans, as they can communicate with one another another. You can tweet Lady Gaga, and who knows? She might respond. That sense of horizontal interaction, however illusory it may be, works to create that sense of community.”

Of course, every artist at the time had Twitter because by then it was the norm, but their accounts were often reserved for promotional tweets and banal interactions as opposed to glimpses into the artist’s personality that felt genuine. Gaga would intersperse funny tweets with videos of her speaking out against “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the US’ now-abolished toxic policy on LGBTQ+ military service members. She would share news of how she was working to fight cyber-bullying with the Born This Way Foundation, or perhaps an image of her “making a statement” in a meat dress surrounded by discharged soldiers. Gaga offered more than just her music, and when she went one step further by creating her very own social network platform LittleMonsters.com, it felt as if she’d actually woven her very own mini-universe for her fans to exist within.

It’s also worth noting that, because so much had been invested into creating a standalone social networking site, the star made doubly sure that she shared selfies, short responses and statements to reassure her fans that it was all worth it. It became the online equivalent of a community centre, where people could participate in multilingual chat-rooms, share memes and even join in listening parties. Gaga herself was known to scroll through the forum: it was here that she sought out die-hard fan (and now member of the fabled Haus of Gaga, a close creative network influenced by Warhol’s iconic inner circle) Emma, who suffers from scoliosis, and paid for her hip surgery. Here, the star even opened up to fans, sharing inside stories and discussing pain, mental health and her experiences in the industry.

It was in 2013 that things truly began to unravel. It started with a debilitating hip injury and spiraled throughout the ARTPOP release campaign, which kicked off with the star parting ways with her management. To make matters worse, she then enlisted controversial photographer Terry Richardson to film a video in which R Kelly, a star whose career has been plagued by allegations of sexual misconduct, “do what he wants” with her body. The video was then canned, with Gaga citing a lack of quality caused by time restraints as the reason it never saw the light of day.

Gaga dealt with these various missteps by seeking solace on her own website. In public, it looked as if things were going gradually downhill, but nobody could pinpoint why. After she spawned a weird painting of a demonic chicken, one fan wrote a lengthy post about their concern for the star, to which Gaga responded. In the ultimately uplifting but still surprisingly candid post, Gaga wrote that she had felt abandoned throughout her hip surgery and as though she were little more than a cash cow to fickle people and corporations – all themes she later expanded on in an excellent keynote speech at SXSW (you know, the one where Millie Brown puked paint down her outfit). Sure, we may now live in a time where Katy Perry live-streams her therapy, but for Gaga to lay her demons bare in such a way to her fans is an example of how she’s interacted with them from the very beginning.

Gaga may not have been the very first pop star to develop such a close bond with her fandom, but she is undoubtedly the first to harness the full potential of the digital age to do so. Of course, her more extravagant experiments with technology don’t always hit the mark—remember that bizarre ARTPOP app that never quite materialized? But, when she strips it back to just posting short responses to her fans, sharing drunken selfies and laying bare the issues she’s truly passionate about, she manages to create a genuine connection which even now feels kind of rare.

This is precisely why Gaga’s blueprint is genius. In weighing in with selfies, memes and the occasional heartfelt post at the same time as being the kind of global icon that can sell out arena tours in seconds, she has molded herself into the ultimate pop star paradox: she can release a self-aware comment on fame like “Paparazzi“, yet you can also imagine getting shit-faced on whiskey with her and setting the world to rights on someone’s sofa at 3AM. It takes more than a meat dress and a few hair bows to curate a fanbase as rabid yet unwaveringly loyal as Little Monsters. Many stars have tried, but without understanding the sense of extended identity that comes from these fan labels. Nobody does it like Gaga.

You can follow Jake on Twitter, and see Esme’s work on her website.