This article originally appeared on VICE US

At the center of two of the 1960s’ greatest exports—New Journalism and drug culture—lies Tom Wolfe’s first book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, and there it has lain, unmoved for some 48 years. Experimental in structure and style, eye-opening in its early accounts of LSD usage, the 1968 book was one of the first non-musical documentations of the hippie movement that accurately reflected its disdain for convention. It was simultaneously of and about the subculture.

Videos by VICE

The words themselves are enough to transport us to squalid Haight-Ashbury squats and the rows of the manically-decorated bus occupied by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. But in pulling out all of the stops, a new repress of the book has added layers of depth in a way no film adaptation or making-of documentary could capture. Taschen’s new collector’s edition (out now through Taschen) combines Wolfe’s words with the photographs of Ted Streshinsky, who accompanied the author on his first trip to San Francisco, and Lawrence Schiller, who partially inspired the book with his photo coverage of the acid scene for LIFE magazine.

Packaged in a fittingly-trippy sleeve adorned with the most iconic photo from Schiller’s 1966 LIFE story (thanks, Wayne Coyne!), the new pressing also includes facsimiles of Wolfe’s original manuscript, concert posters, and Kesey’s arrest records. A trade edition is on its way next year, but for now, it’s limited to 1,968 copies, making it feel like the text equivalent to a vinyl junkie’s wet dream.

This Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test edition is the second in a series of imaginative represses spearheaded by Schiller. Aiming to “bring together the great New Journalism and the great photojournalism of the second half of the 20th Century,” he’s already overseen an edition of Gay Talese’s famed essay “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” that includes Phil Stern’s photos of the singer, and is now working on combining James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time with Steve Schapiro’s photos from the Civil Rights movement.

Schiller clearly has a passion for this revolutionary era of journalism, but The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test holds special significance for him. Not only is it the only book in the series of represses to contain his photos, but Schiller also says that reading it changed his life, with Wolfe’s unique approach opening a world of possibilities in his young, hungry mind.

Soon after Acid Test‘s release, Schiller pivoted from photojournalism to writing and/or collaborating on books, and eventually films, based on extensive interviews he’d accrued from stories on Lee Harvey Oswald, Lenny Bruce, the Manson murders, and others. Although successful in his first profession, it wasn’t until his second act that his work began winning Pulitzers (for Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song) and Emmys (for four of his made-for-TV films or miniseries). Without Wolfe’s complete shattering of journalistic conventions in this book, it’s doubtful that Schiller would have ever considered a career change. VICE spoke with Schiller over the phone to learn more about his involvement with the original book, its fancy new repress, and how Tom Wolfe rocked his world. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The multicolored Merry Pranksters’ modified 1939 International Harvester school bus, nicknamed “Further.” San Francisco, 1966. Photo by Ted Streshinsky, Photographic Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

VICE: So your role in the original creation of the book was basically inspiring Tom Wolfe, or at least being his first source.

Lawrence Schiller: He’s said that seeing my original LIFE magazine essay inspired him to expand his original idea for New York magazine—which was to do a story on Ken Kesey getting out of jail—into a greater book that covered the entire acid scene.

At that time, he didn’t understand the full range or horizon of the acid experience. In my original essay, I didn’t cover the Merry Pranksters on the road. I didn’t cover Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. But I did cover Timothy Leary’s trial in Texas, and did a book with [early LSD researchers] Dick Alpert and Sidney Cohen. I think I showed Tom another side of the picture.

Are there any of your photos in here that were never published, in LIFE or otherwise?

Yes, many of them. Whether a picture was published or not, what’s more important is that this is the full [photo] essay. You now really get the full picture of what I call “set and setting.” You really visually understand the context in which the author, Tom Wolfe in this case, wrote his extraordinary piece, first for New York magazine, and then for the book.

The Acid Test Graduation, Halloween night, 1966, held at the Merry Pranksters’ warehouse/headquarters on Harriet Street in San Francisco’s Skid Row area. Photo by Ted Streshinsky © 2016 The Estate of Ted Streshinsky

What was the curation process like? Who was involved?

The concept of the series was mine, and I worked very closely with executing it. Being a photojournalist myself, I have a very strong hand in the photography that goes into it. The editor, who’s the same for the whole series, is Nina Wiener, and she’s really responsible for recommending excerpts to the author, and determining how that excerpt should be integrated and broken down with the photography. Her forte is really marrying the photography with the text. It’s not an easy job, you don’t just throw pictures together. So she works with Taschen in that area, and then as the book comes down, I review everything. I’m responsible for retouching every photograph in the book—I’m still doing that, only because of my love for photography, rather than just turning it over to a technician.

The repress feels pretty exhaustive, but do you feel like there’s any more material surrounding the book that’s yet to be uncovered?

I don’t think so, at least not in terms of Tom’s work and Ted’s accompanying photos, which made up the original project. Of course, you could gain added perspective by reading Kesey, Leary, Ginsberg, or Hunter S. Thompson’s Hells Angels book—any of the works by the various authors and artists who are either characters in the book or just mentioned in passing.

Hollywood Acid Test, February 25, 1966. Photo by Lawrence Schiller © Polaris Communications Inc.

Your photos in particular use some techniques—strobe lighting, blurred movement—that attempt to simulate psychedelic experiences.

It’s funny, I showed those photos to Leary and he said, “Well Larry, until you take acid yourself, that’s what you’ll think the experience is like, but it’s really not about that.” It’s a photographic device in which I try to heighten the visual experience to say that the acid experience is heightened also. Photographers use techniques to try to explain what the experience is. It’s like shooting sports and using slow shutter speeds, blurring the action to try to give the feeling of speed and movement.

You’re mentioned briefly in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, when you come in to shoot those strobe photos. But from your new introduction in the repress, it sounds like you were either unaware of the book being written or not in touch with Tom at the time.

I was unaware that he was writing a full book, because when he called to interview me, he was still writing the New York magazine article. I didn’t know that he was expanding it—by that time, I was already onto other assignments all around the world.

What was your initial reaction to the book when it first came out?

My first impression of the book had nothing to do with Tom, but something totally to do with me. I’m dyslexic, I can’t spell, and I can’t read very well. But I didn’t know that I was dyslexic at a young age. Not until I was around 50 did the word “dyslexia” even exist.

I was always tape recording interviews, and I always had a desire to write. Every photo assignment I had, I was doing long interviews, 10-15 hours worth. When I saw, perused, and read some of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, all of the sudden I realized, for the first time as a young photojournalist, that a writer didn’t have to be at every goddamn location to write a great book, and that a writer only had to have a small piece of the experience if he had the ability to include his own look at things.

A week after I saw what Tom had done, I went out and hired Albert Goldman to write Ladies and Gentlemen—Lenny Bruce! I had already interviewed everybody [necessary for the story]. That became a bestseller and made Albert a top author, then we did a Broadway play, and I became a partner in the film adaptation with Dustin Hoffman. I hired Norman Mailer to write four books based on my ideas and interviews. I hired Wilfrid Sheed to write a book—various writers did different books for me. Tom’s book changed my entire life, because from then on I realized that my [investigative journalism] work could be expressed by using the creativity of other writers, who could contribute their ideas on the subject.

I’m not exaggerating, I interviewed 150 people for some of my stories. And I would spend six months just doing interviews, sometimes I didn’t even have a camera with me. I was always using a tape recorder, and now my archives consist of 1,800 boxes in storage, and that’s how I was able to provide Mailer with everything that produced the Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Executioner’s Song, and I went on to direct the film.

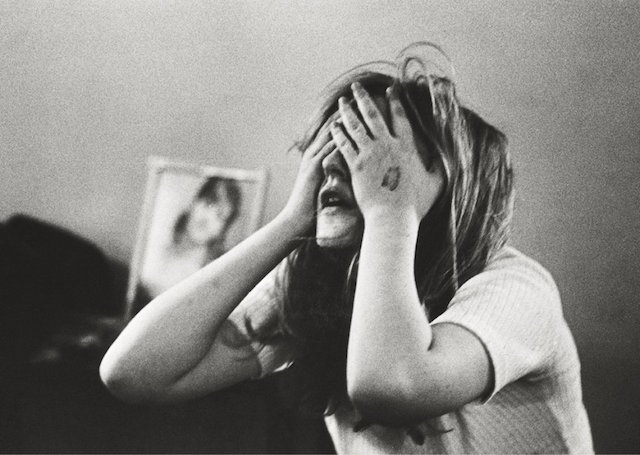

A first-timer in the throes of a bad trip. “I experienced the desire to die, but not actual death,” she later said, “very strongly the desire to rip my skin off and pull my hair out and pull my face off.” Photo by Lawrence Schiller © 2016 Polaris Communications Inc.

I see similarities in the way you describe your approach and Tom’s style of reporting. Both seem very reliant on immersing yourself in the story, not just fading into the background and observing.

You always have to figure out your way in. Maybe I had one or two rough weeks—I never wrote about this, but I actually got arrested doing the story.

In Hollywood, I was photographing a young lady tripping in a supermarket, and she almost had a full blown psychosis—it was really horrible. She calmed down, I got her out of the emergency room, and I discovered that she was from Scarsdale, New York. I asked her if she wanted to go home, and she said “yes.” So I bought us both airplane tickets, took her home, and I drove out Scarsdale with her. I knock on the front door, her mother opens the door, and I realize this young lady had been a runaway. She hugged and kissed her father and went inside, and I just sat on the front porch.

About five or ten minutes later, two police cars pull up and arrest me. Her parents thought I was responsible for their daughter running away! It took me an hour at the jail to prove that I was a LIFE magazine photographer—they had to call the photo editor of the magazine. Finally I was released, but it’s funny, sometimes you submerge yourself so deep in the story that you become part of it.

See more photos from the repress below. And order the collector’s edition of “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” out now via Taschen.

Follow Patrick on Twitter.

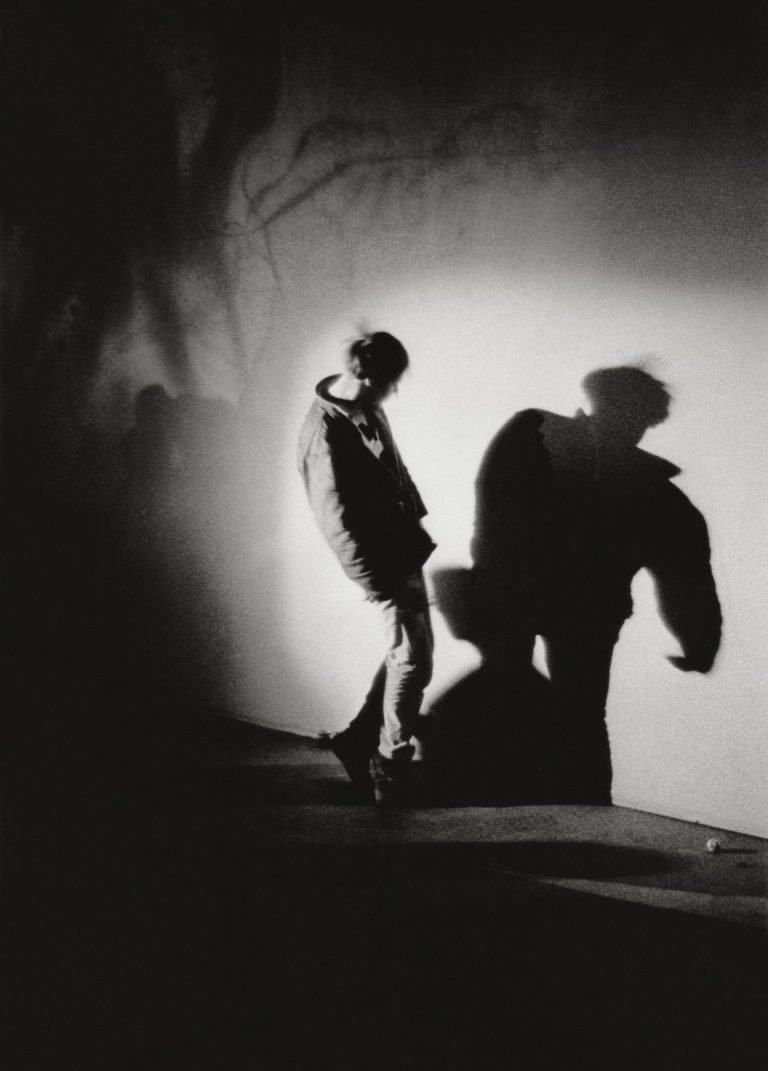

Me and My Shadow, Hollywood Acid Test, 1966.Photo by Lawrence Schiller © 2016 Polaris Communications Inc.

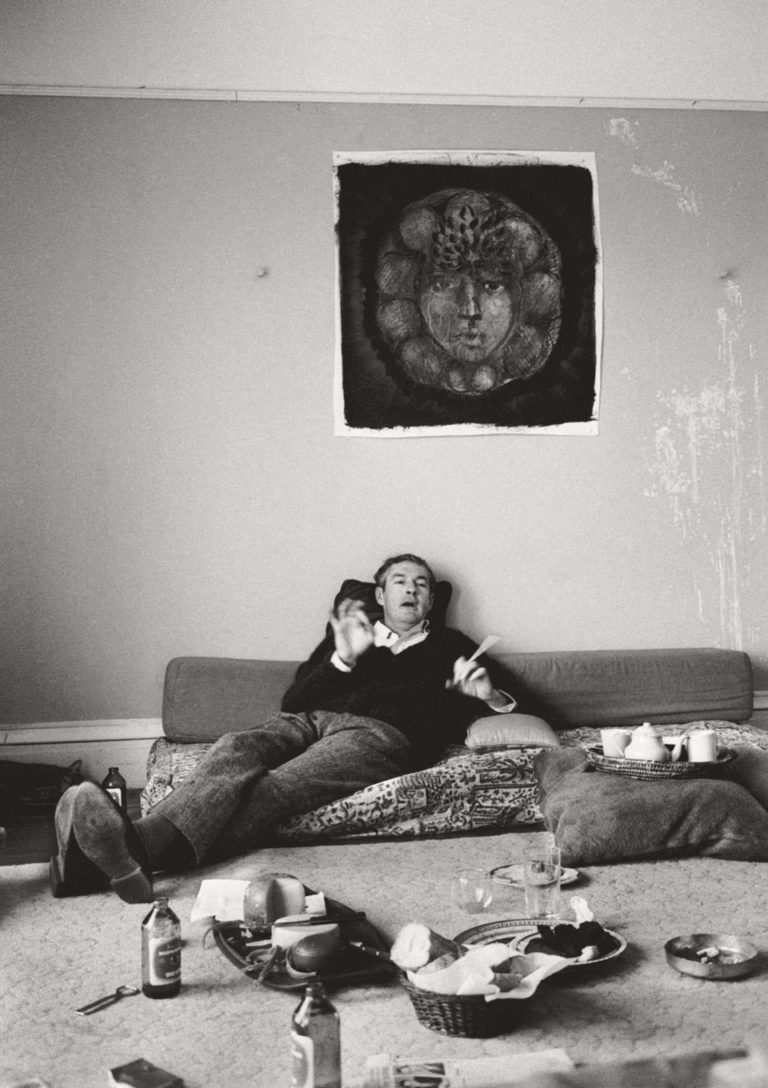

Dr. Timothy Leary photographed in San Francisco, 1966. Photographs by Lawrence Schiller © 2016 Polaris Communications Inc.