Islington, London

Ali Mobasser had an unsettled childhood. Born in the US, by the age of eight he’d lived in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Costa Rica and the UK. Fleeing the Iranian Revolution of 1979, he was sent to London to live with his aunt Afsaneh and his father, later turning the city into the subject and inspiration of his award-winning photography.

His series “Afsaneh: Box III” documented photographs of his aunt’s ID cards and school reports, earning an award back in 2014. But “Reflections”, his most recent work, is a series of street photography shots inspired by his “son’s fearlessness to engage with the world around him”. It narrates a journey of acceptance and mourning after his Aunt Afsaneh passed away in 2013. Ali told me the series has been tactically hidden on his website, to give him the opportunity to perfect the concept.

Videos by VICE

While Ali fiddled around with his Rolleiflex camera, we talked about his dislike for genres within photography, his son’s involvement in “Reflections” and dealing with the people he pissed off along the way.

VICE: You studied fine art, so what led you to photography?

Ali Mobasser: I was too scared to become an artist. I didn’t feel like I had enough issues because artists need “issues” to deal with. And I was 20, issue-free. I was doing a lot of photography in a darkroom the whole time, so after university I thought I should just go down the photography path and start assisting. And then through that, I can try to be an artist. But I took a while to call myself a photographer.

Why was that?

I saw myself as an artist who uses photography. Fine art was mixed media, so it was all about the idea. You would have a concept and then you would use whatever medium you want to conclude that idea. I was always looking at photographers like Hiroshi Sugimoto and Duane Michals who never identified as photographers, so I always respected them. When I saw you could do conceptual storytelling with photography, and people could find their own stories within that, that’s what really what attracted me.

I read on your website that your late aunt raised you in Putney. How did that influence your work?

I didn’t want to go to Putney. I was sent there on a holiday when I was eight years old from California, where I lived with my mother. At the end of that summer, there was a phone call where my mum told me I was staying. So I was stuck. I had this really sort of strange upbringing where I never knew what was going to happen.

I felt like Putney didn’t have an identity, and I had never photographed London. The challenge for me was to photograph a home that didn’t really feel like my own. Putney’s always felt like a place with an identity crisis. All the old people disappeared, all the people from the estates disappeared and now it’s this place that’s quite posh.

You’ve said the “Reflections” series was inspired by your son’s “fearlessness” and “unabashed willingness to engage with the world around him”. Can you tell me more?

When he was out of the pram, I really started taking these photographs. What happened was he’d go out with a scooter and dive into these social situations. I would never stand in front of someone just like that and take a photograph. So I would go in and be like, “Farris, come here! Sorry about that.” Then as this was happening, I’d take their photograph.

When I started taking photographs in London, my home environment, I discovered the work of Vivian Maier [the pioneering street photographer who worked as a nanny and was unknown as an artist before she died in 2009]. She was using kids as a decoy as well, also shooting on the Rolleiflex.

I think street photography is the hardest kind of because you’re vulnerable. You get caught. The most powerful images for me are the ones where they’ve caught me and they’re looking at me like, What are you doing? It’s like doing something naughty, something sneaky. You can hold the Rolleiflex one way and be pointing the lens another and people don’t know what you’re doing because they don’t know what the camera is.

Finsbury, London

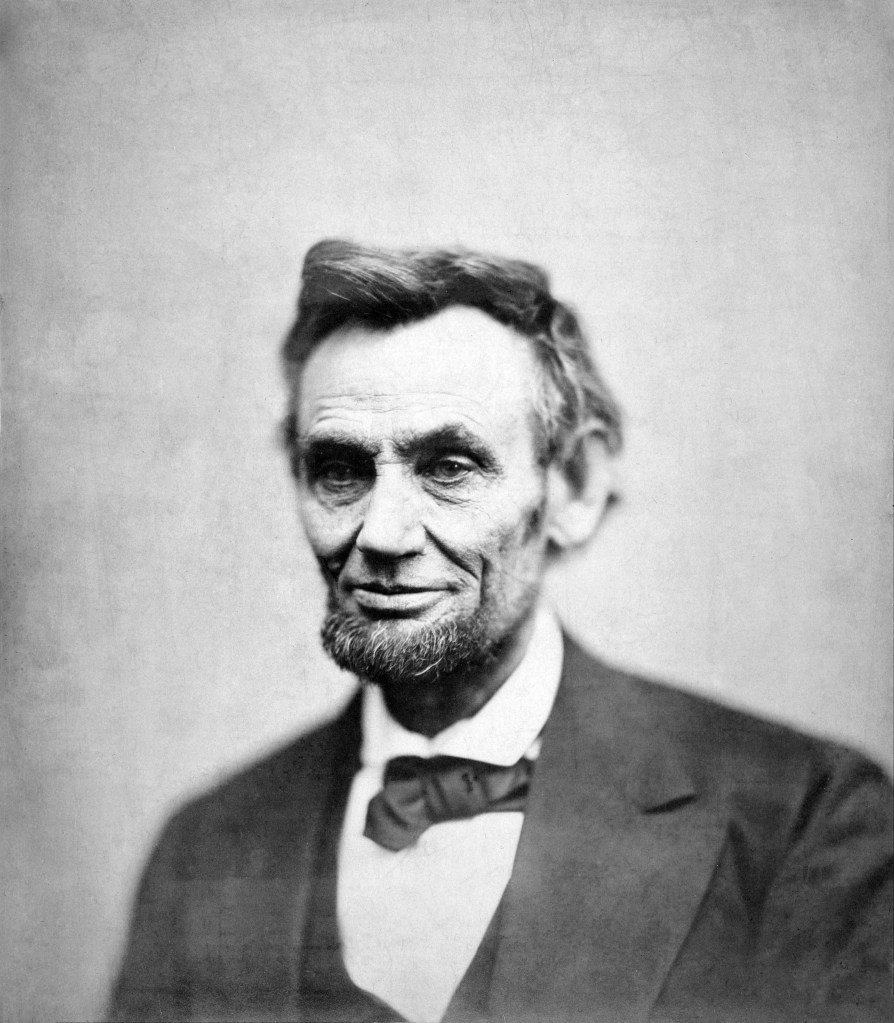

Has anyone got really angry?

Yes. She did [above]. I kind of just killed her with kindness and had a laugh with her afterwards. But she still wasn’t happy. I explained to her how amazing she looked. Another guy came and pulled her away, but she was like “Delete that. Delete that now!” Then I started explaining that it was on film, and just a mirror thing I look into. So I kind of got away with that.

Do you ever feel you’ve crossed a line?

I go into the situation and I take the photograph. Sometimes I question, Am I taking the right photograph? Is this something I should be showing? But I don’t think about that when I’m taking the photograph. I just take it and that’s what becomes a reflection of myself. Then afterwards I decide within the edit whether I’m going to use that photograph or not. There’s images I don’t feel are me. I try not to be mean. I still might take that mean photograph, but then I’ll look at it and decide, No I can’t use that if it doesn’t feel fair, however good the photograph is. But there are still a few images in here that I’m questioning.

How so?

In one photograph, I think the mother wasn’t well. I was in the area with my friend and his daughter, who were having fun. My friend asked me to take his photo, then to the right was this situation. My wife thought it was a powerful shot, but I questioned whether I was exposing someone’s life that maybe they don’t want to be exposed like that. So I find that one quite tough, and I will probably will get rid of it. That’s why Reflections has been taken off my website, because I’ll have to re-edit this.

Street photography is described as a saturated market. How do you stand out?

Street photography wasn’t something that was that attractive to me. I was never a big Cartier-Bresson fan. I just found I enjoyed taking photographs of what’s around me. Sometimes I find it hard calling it street photography because a lot of it’s not on the streets, and there’s personal stuff drifting into it. And that’s why instead of calling it observations it’s called reflections.

I’m kind of battling with this series at the moment and I know it’s getting to where I want it to be. Once, there was a woman wearing a pink sari and behind her was a pink double decker bus. What are the chances? But I took it out of the series because it’s really obvious. It’s just a colour thing going on. If I’ve seen it before, it’s a perspective trick, a colour trick or visual trick and there’s nothing being said, then I pull it out. And that’s why my work isn’t street photography – street photography is always visual play.

Thanks, Ali.

This interview has been condensed for clarity and length. Here are some more photos from the series.

Oxfordshire

Caledonian Road, London

Holloway Road, London

Caledonian Road, London

Charing Cross Road, London

Clissold Park, London

The English Channel

Highbury Corner, London

Kings Cross Station, London

Covent Garden, London

Angel, London