“Watch out – there are snipers on this street,” warned the jihadist, as my driver stopped next to him and eight other heavily armed men who were preparing to head into battle. He and the other fighters were from a group known as the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham – or ISIS – which is an offshoot of al-Qaeda currently operating on the battlegrounds of Syria.

He wouldn’t have guessed it, but we were all trying to reach the same place – the frontline outside the headquarters of yet another of the militant groups fighting in Syria, Ahfad al-Rasul. This organisation is affiliated with the Free Syrian Army and had declared war on ISIS just a few hours earlier, for control of the provincial capital of Raqqa.

This was my third visit to the city in the four months since it had been “liberated”, as Syrians tend to refer to areas where rebels have managed to expel government troops. The battle against Bashar al-Assad’s forces in Raqqa had only lasted for about a week – a sharp contrast to the fighting in Aleppo, where gunfights and shelling have continued for over a year since the conflict began.

Videos by VICE

Members of a Free Syrian Army batallion help run a bakery that provides bread at low prices to civilians in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

Once rebels take control of an area, it is now standard procedure for the regime to respond by bombarding it with indiscriminate air strikes in the hope of killing swathes of anti-Assad fighters. But back in April, just weeks after the liberation, cheerful residents seemed to greet the inevitable trail of destruction as a good thing – a sign of the progress the rebels were making.

Recently, however, the tension has risen considerably in Raqqa and the atmosphere has completely changed, as the rebel resistance continues to splinter, pitting many groups who once fought side by side against Assad against each other. The original celebration of freedom has given way to fear and uncertainty.

A number of civil movements – both religious and secular – have also been trying to establish themselves in a bid to influence the future of the city and eventually the country. A group named Haqna – Arabic for “Our Right” – is one of the organisations leading the charge. Its logo – a hand making a V sign, the index finger marked with election ink – is spray-painted all over the city. Mostly made up of young local activists, Haqna is aiming to educate the population about their civil rights and the importance of elections.

Children play with the remains of a statue of the president’s brother, Basil al-Assad, destroyed after the rebels took control of the provincial capital of Raqqa.

However, Haqna have already met opposition from ISIS, and some of their members have been arrested recently for organising protests against the militant Islamist group. After a demonstration outside their headquarters, one activist claimed to have seen someone filming them from inside the building. “They’re worse than the mukhabarat [the secret police] – they have eyes everywhere,” he said.

While members of ISIS currently occupy Raqqa’s governorate building – their black flag raised high in the main square outside – it is the independent Islamic movement of Ahrar al-Sham that plays the most significant role in the administration of the city. The group has been maintaining essential services such as garbage collection and water and power supply. It also manages public bakeries and distributes food relief packages to thousands of families in the province, as well as promoting Islamic education through public lectures, workshops and religious and philosophical messages painted on public walls and posters across the city.

Which doesn’t mean the group isn’t fully engaged militarily. Though the city is controlled by the rebels, an area around 1km outside of the city is still disputed with Division 17, a unit of Assad’s army, and Ahrar al-Sham’s fighters are the main rebel force in the battle. I asked one of their fighters when he expected Division 17 to be overtaken. He quickly replied, “I hope not any time soon,” clearly aware that the regime would respond with air strikes, causing civilian casualties in the process.

The body of a child killed during a barrel bomb attack is prepared for burial in Raqqa city.

I’ve had first-hand experience of that problem myself; at the end of Ramadan, I was woken by the sound of a fleet of ambulances rushing by – it turned out that Syrian army helicopters had dropped bombs on three different buildings, killing 13 people. Within a few hours, I found myself standing in the refrigerated room of a morgue with a father as he watched the bodies of six of his children being wrapped up in burial sheets.

The family waited until the evening for the funeral to avoid being caught in another attack, as funerals are often targeted by shelling from the regime. A rebel manning a heavy machine gun – or a “dushka”, as they’re colloquially named – on the back of a pick-up truck followed us for protection.

Three trucks carried the bodies, along with the mourners. All the way to the cemetery, I watched as a young boy sitting on the back of one of the trucks wept over the body of one of his six murdered siblings. Bystanders, mostly families who had been enjoying a cheerful Eid evening, stood silently and watched the procession pass, the palms of their hands held face-up in respect. A man announced the martyrs: “Shahid! Shahid! Six brothers and sisters!”

Islamist rebel fighters pose for portrait inside the opulent governor’s palace in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

Once we arrived, there was no time for ceremony. The burial had to be carried out in a rush because of the site’s proximity to Division 17 troops, and our lights had to be turned out in case they attracted any remaining Syrian army officials in the region. A number of men helped hand over the bodies to the father as he stood inside the massive open grave. Others held their phones up to provide just enough light for the bodies to be laid in the right place. After a few minutes, we left.

Back at the HQ of Ahfad al-Rasul – which the group had established in Raqqa’s non-operational train station, where we’d been heading when we bumped into the ISIS fighters – I sat with Abu Mazin, the commander who’d just declared war against the militant Islamist group. His men had set up barricades all around the station.

Describing his group as a military organisation with no political affiliations, Abu Mazin talked about a larger project that Ahfad al-Rasul is part of. “We are working to unify all FSA groups under the National Security Council,” he told me. “In the future, we will form the Syrian National Army.” Abu Mazin continued, assuring me that his group have no particular ideology: “We are only Syrians for all. We can’t keep Syria together as one if we want to keep a single ideology.”

Women at a public demonstration to remember and honour those who lost their lives during the battle for control of the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A local resident, Abu Mazin said the main reason that he declared war against ISIS is to fight for the release of a reported 1,500 prisoners currently being held by the group, about 500 of them FSA members. He also said that he had the support of Raqqa’s residents: “The people don’t want to be under the rule of ISIS,” he explained.

The interview was kept short, as Abu Mazin and his men were somewhat preoccupied with the battle they’d started only a couple of days before. During that time, he claimed his men had killed or injured 40 ISIS members, while suffering only three injuries in their ranks. “This is my city. They cannot defeat us in an urban battle here,” he told me.

Before leaving, I asked him if I could photograph his fighters on the frontline. “Sure, but please don’t show their faces,” he responded. “They are afraid of ISIS.”

The following day, before I left Raqqa, I thought of calling Abu Mazin to ask him a few more questions, but my phone rang before I could dial his number. A car bomb had hit his headquarters; killing him and all the men I had met on the previous day. “It’s over,” said the activist who called to share the news. “ISIS won.”

Follow Alice on Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/martinsalicea

More on Syria:

This Munitions Expert Says Assad Is Responsible for the Syria Chemical Attacks

What Would Western Intervention in Syria Look Like?

More and More Journalists Are Being Kidnapped in Syria

WATCH – Ground Zero: Syria

Six members of the same family, victims of a barrel bomb attack, are buried in Raqqa. The burial was made during the night and in a rush amid fears of another attack.

A Syrian rebel fighter at a public gathering where locals honoured the martyrs who fought for the control of the capital of Raqqa.

A child runs through the rubble of a home destroyed during an air strike in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A commander and members of a Free Syrian Army battalion in their headquarters in Raqqa.

Members of a Free Syrian Army batallion help run a bakery that provides bread at low prices to civilians in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

One of the local leaders of the Islamist rebel group Ahrar Al-Sham, responsible for overseeing the campaign to paint phrases of advice in public places in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A member of the Islamist rebel group Ahrar Al-Sham paints a phrase meaning “Religion is Advice” on a wall in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A man burning garbage in a metal container as children in the background spot an army helicopter in the sky. Shelling and air strikes have been sporadic in the month since the rebels took control over the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A boy selling military clothing and accessories at a busy street in Raqqa holds a Shahada flag.

Women at a public demonstration to remember and honour those who lost their lives during the battle for control of the provincial capital of Raqqa.

A Syrian woman stands outside a bakery managed by the Islamic movement of Ahrar al Sham in the city of Raqqa during the holy month of Ramadan.

People walk along a shopping street at night during the holy month of Ramadan in the city of Raqqa.

Women in a shopping street at night during the holy month of Ramadan in the city of Raqqa.

Abu Tayf, commander of the Omnaa al Raqqa rebel brigade, holds a newborn child who was found abandoned at a nearby public garden. He recites the adhaan – the very first words a newborn Muslim child should hear. The child’s parents were later located by his brigade.

Local volunteers walk through the debris after a barrel bomb dropped from a Syrian army helicopter destroyed two homes. Fourteen civilians were killed in this attack. Two more attacks destroyed buildings and injured dozens of people.

Women react as they reach the scene of an attack where a barrel bomb dropped from a Syrian army helicopter destroyed two homes and killed 14 civilians.

Children walk through the debris after a bomb dropped from a Syrian army helicopter hit a residential building.

The body of a child killed during a barrel bomb attack is prepared for burial in Raqqa city.

The bodies of six members of the same family killed during a barrel bomb attack are prepared for burial in Raqqa city.

A young man mourns the deaths of six of his siblings during a barrel bomb attack in Raqqa.

A damaged picture of president Bashar al-Assad in a public garden in Raqqa, the first provincial capital completely controled by Syrian rebels.

Members of the FSA-affiliated rebel group Ahfad al Rasul are seen outside their headquarters in Raqqa, Syria, fighting against members of the Islamic State in Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) on August the 12th, 2013.

A street vendor walks past a shop where the message, “The thief will be punished – Jabhat al-Nusra,” was spray-painted on the door. Since the rebels expelled the government from the city of Raqqa in early March, many shop owners have chosen to write similar messages for fear of looting.

A barber shop in Raqqa, where some young men have visited to change their beard style after being inspired by Islamist rebel fighters.

Islamist rebel fighters pose for portrait inside the opulent governor’s palace in the provincial capital of Raqqa.

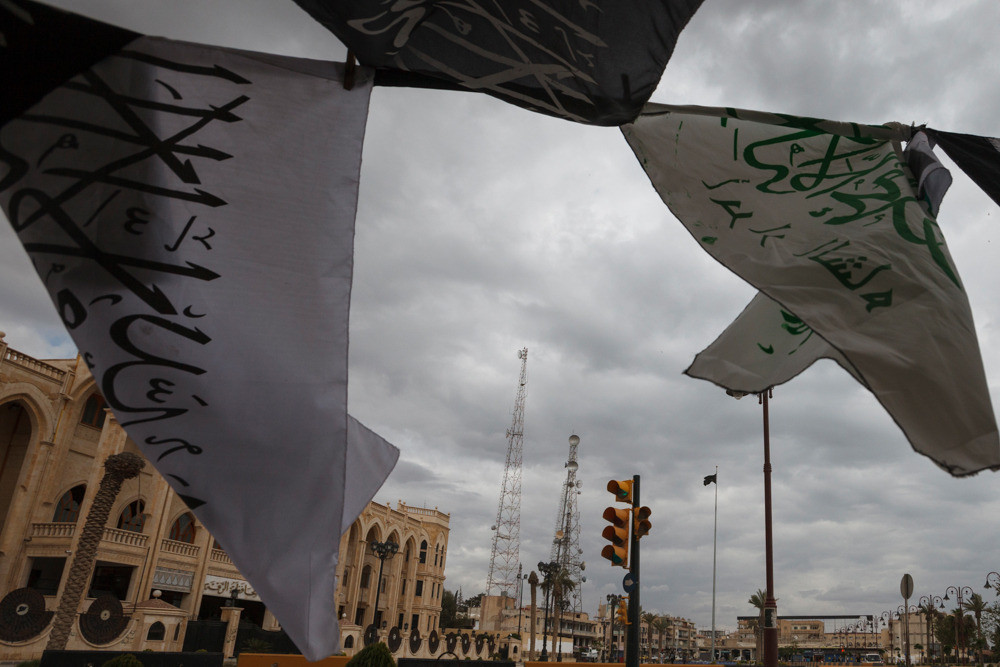

The controversial black flag raised by an Islamist group across from the governorate building in Raqqa is seen on the background of a street stand where flags representing different rebel groups are sold.

Children play with the remains of a statue of the president’s brother, Basil al-Assad, destroyed after the rebels took control of the provincial capital of Raqqa.