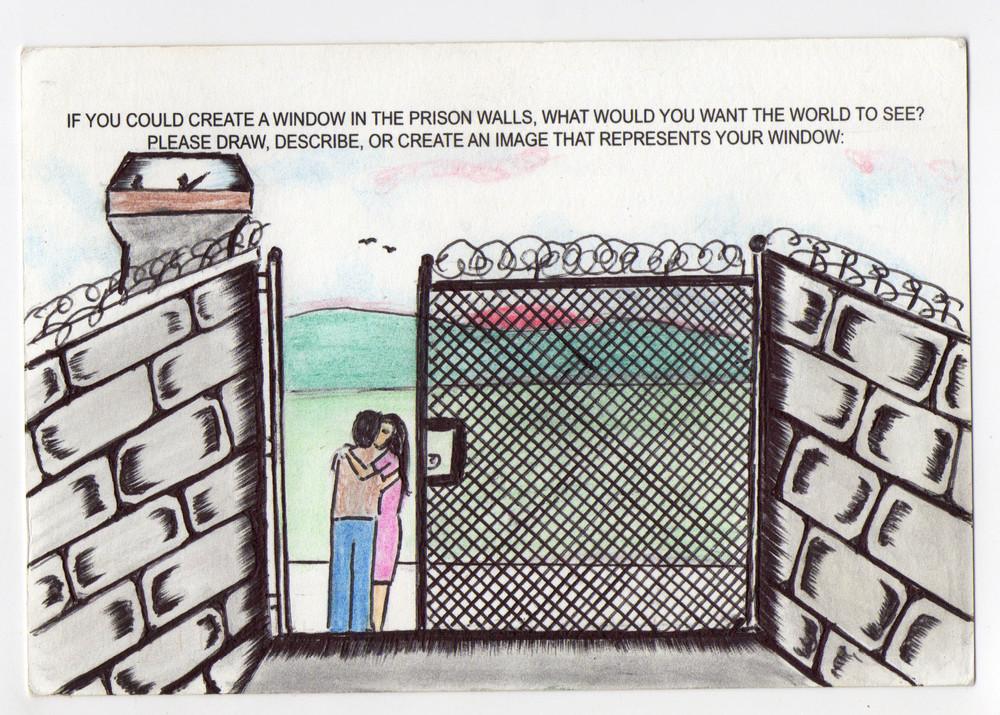

This postcard is part of and ongoing project called ‘Postcards from Prison,’ a collaboration between artist Mark Strandquist and Prison Health News. Their goal is to get prisoners across the United States to use postcards to answer the following question, “If you could create a window in the prison walls, what would you want the world to see?”

Mark Strandquist is an artist, activist, and educator who has produced all sorts of projects that engage with and promote discussion about the criminal justice system. He contributed images from his series Postcards from Prison to the prison-themed October issue of VICE Magazine. I wanted to learn more about his work, so I called him up recently to chat about where his art intersects with activism, what people can do to change the prison system’s abuses, and why he has hope for the future.

VICE: You’ve been doing activism-based art projects for a long time across several different mediums—where did it all start? What motivated you to do this work?

Mark Strandquist: There’s an amazing quote from Angela Davis that I include every time I present my work:

Videos by VICE

The prison… functions ideologically as an abstract site into which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting those communities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionate numbers… It relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society.

To me, she provides such a powerful call to action. [The question is not just] how collaborative projects with incarcerated men, women, and teens can bring their voices, struggles, and dreams into the public spaces that typically silence or exclude them—but, importantly, how those exhibits, performances, or publications can create stages for bringing hundreds, sometimes thousands of people together, to engage, question, and attempt to transform the very social structures that are leading to such high rates of incarceration.

Art, like any fiction, is an amazing space to reimagine and perform a more just society. All politics are performance art, it’s just typically a stage that excludes those individuals most impacted by the criminal justice system.

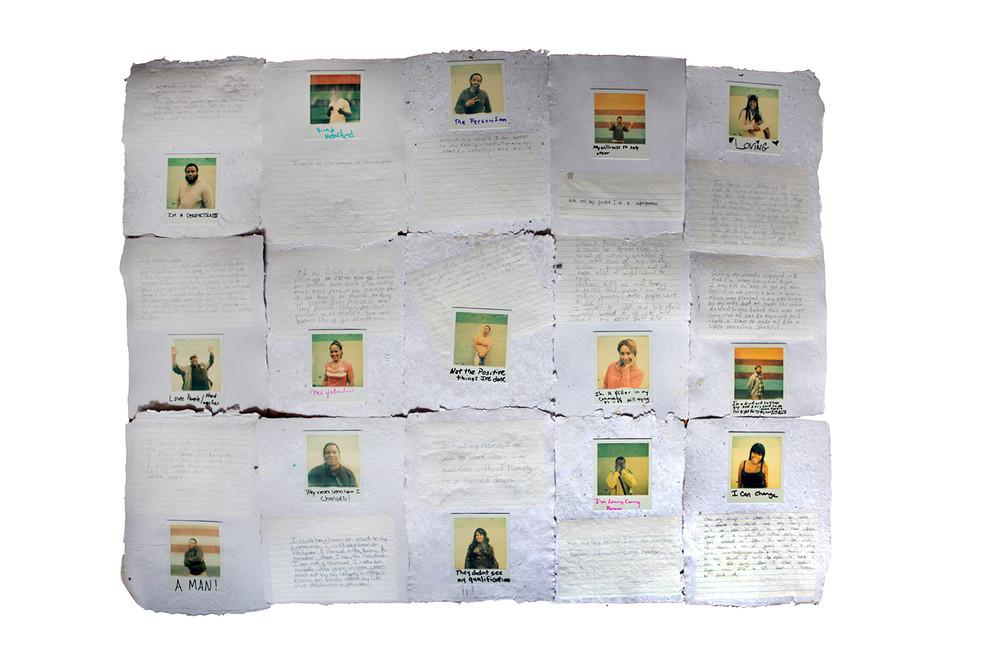

The People’s Paper Co-op (PPC) has worked with hundreds of individuals across Philadelphia to produce a giant paper quit of pulped criminal records, polaroid portraits, and community reflections. Every month the PPC partners with the Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity (PLSE) to organize and facilitate free legal clinics in Philadelphia. In each clinic, participants work with lawyers to clear or clean up their criminal records. Participants then print out their records, tear them up, and put them in blenders to create new blank sheets of handmade paper.

Windows from Prison, the People’s Paper Co-op, Performing Statistics… all of these projects share a core ethos—that we need to listen. That we need spaces to connect across difference. That discomfort is essential to justice.

It’s been such an honor to work with so many brilliant and beautiful people throughout these projects. Each iteration is building on the last, and I believe we’re finally beginning to see change on the personal, community, and legislative levels.

We featured some of the work that came in from Postcards from Prison, where you collaborated with Prison Health News and created an open call to inmates asking, “If you could create a window in the prison walls, what would you want the world to see?” What surprised you most about the drawings and information that came back?

Most of my work is centered around the idea that the people most impacted by any issue (in this case incarcerated men and women) are the very experts that society needs to listen to. Postcards from Prison began with that concept in mind. If we looked to incarcerated men and women as photojournalists what “images” would they create? What windows into their experience would they want to share with the world? Working with PHN we sent thousands of blank postcards to incarcerated men and women across the US. The postcards move in a multitude of ways: from deeply personal narratives of isolation, to resilience and self-determination in the face of extreme obstacles, to complex criticism of the criminal justice system, to regrets, forgiveness, self-love, and self-blame. At its core the project is about creating moments for listening and learning. Something that I believe many photos of prisoners fail to do. Something that is so important for our society to truly reimagine this system.

What are common misconceptions you find people make about inmates in general?

I often ask people at our exhibitions or public talks, “What is the first image that comes to mind when you hear the word prison, or prisoner?” All over the country I hear the same responses: orange jumpsuits, hands on bars, jail cells, concrete… People have seen so many of the same images in film, on nightly news, in music, books, and throughout our mediated culture. Collectively they’ve manifested what I believe is a very limited understanding of the actual human beings, the actual experience of incarcerated, let alone the struggles, inequalities, trauma, and structural violence that occurs in the communities that so many prisoners come from.

Children across the US are surviving childhood, not experiencing it. That’s a radically important distinction to make. During a workshop with incarcerated youth in Virginia I was once told, “If you believed you would be dead or in prison by 21, what would you do? How would you act?”

It’s so important that prisoners are creating their own media. It’s a huge first step, we need to transform the narratives that have helped shaped the very policies that have led us to this crisis.

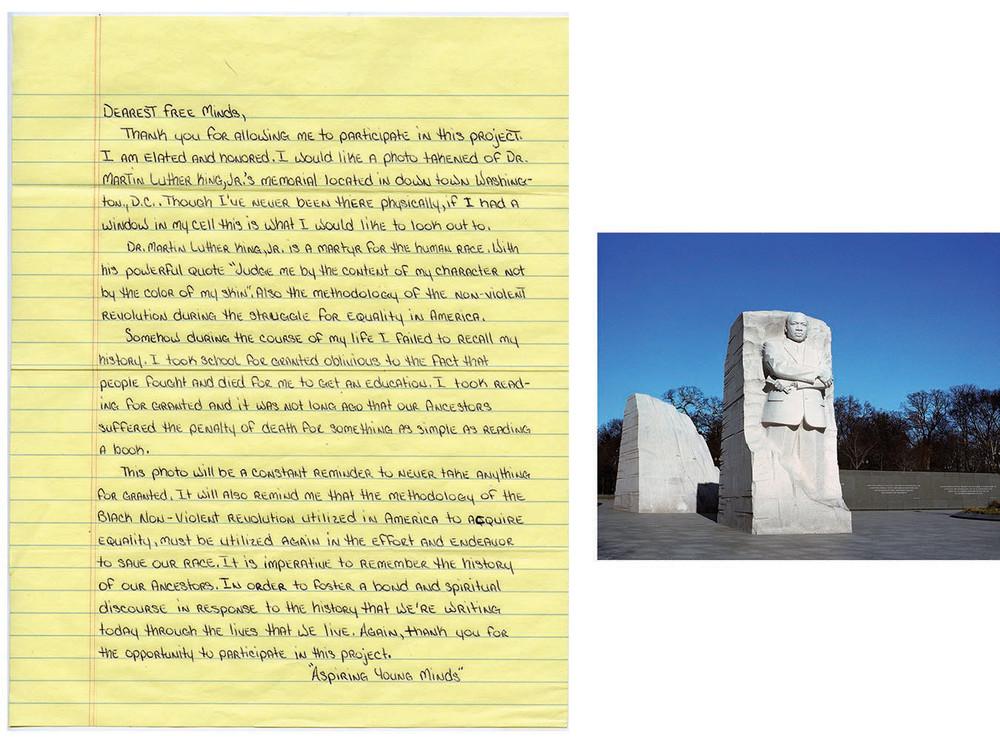

In the ongoing project ‘Windows from Prison,’ images requested by prisoners are collaboratively produced by students, former prisoners, artists, activists, and many others. Once the images are produced and given to the corresponding prisoners, the images are blown up on banners and publicly exhibited to spark dialogue and action around criminal justice issues.

In your most recent project, Performing Statistics, you collaborate with incarcerated teens. How do you think they can change the system through this project?

Our project began with the questions, “How would criminal justice reform differ if it was led by incarcerated teens? How could socially engaged artists, educators, and Virginia’s leading policy advocates support and ensure the success of their vision for a more just society?”

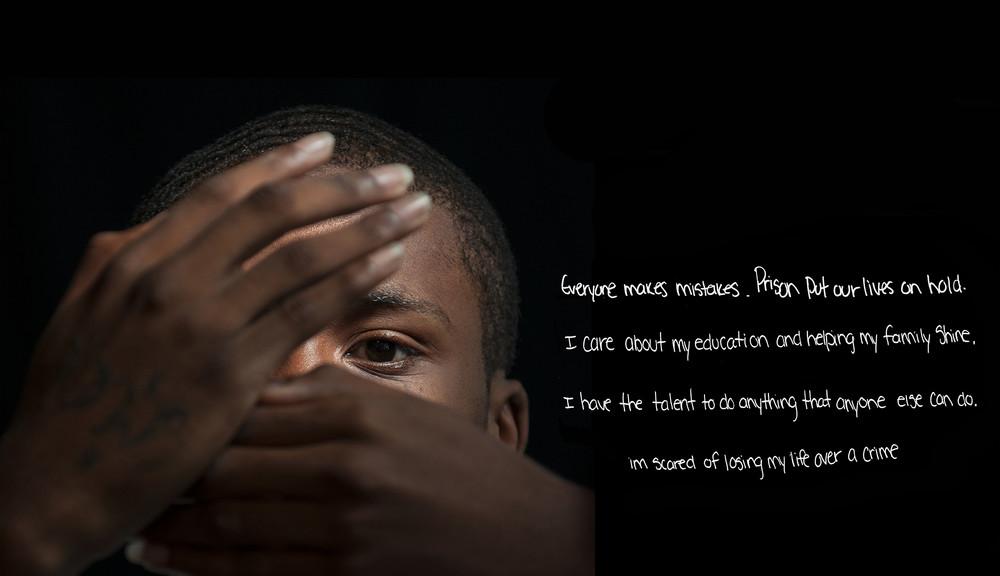

This summer we worked with a group of incarcerated teens in Richmond, Virgina. Three days a week for eight weeks the teens were able to leave their prison and come to Art 180, a window-filled art space that was the antithesis of a detention center. They were able to wear their own clothes, speak about anything they wanted, and work in a room without any guards. Every week they worked with an amazing group of artists, activists, and legal experts from Legal Aid Justice Center to create projects about their lives and their visions for a more just world. It was important to not only work with the youth to use art to envision a world without youth in prison, but to model how an alternative program could look and function.

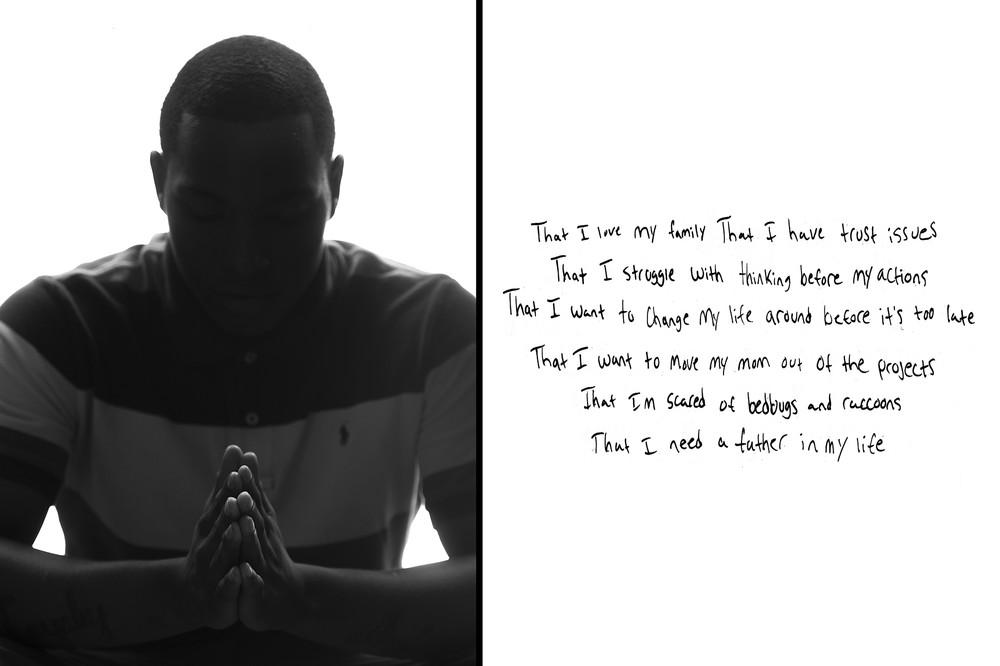

Self-portraits created by an incarcerated youth in the Performing Statistics project. These images have been printed on 12-foot wide banners for public installations where they will be seen in schools, governmental buildings, museums, and public events, including a parade on November 6, where they’ll be marched down Richmond’s main avenue. To hear a poem written by this teen, call 804-234-3698, extension #2

The projects they created include PSAs about their lives that will be broadcasted on radio stations across Virginia, their own police training manual incredible photographs that have been printed on giant photo banners for a mobile exhibition that will tour across Virginia, silk-screened posters and T-shirts that have been given out to hundreds of people, protest chants that a marching band is translating into a score for public performances, and a to-scale model of a prison cell that includes poems written by the youth burned into the floorboards.

Honestly, I’ve never had this much hope. The head of Virginia’s Department of Juvenile Justice is holding a town hall meeting in our exhibit this month. Richmond’s police chief is bringing all of his new recruits to see the installation and use the exhibit and the manuals the teens created to help train his officers. Teachers across Richmond are developing a curriculum for the project. We’re going to print a newspaper with the teens’ art and curriculum suggestions so that we can connect with students and educators across the state.

To hear a poem written by this teen, call 804-234-3698, extension #4

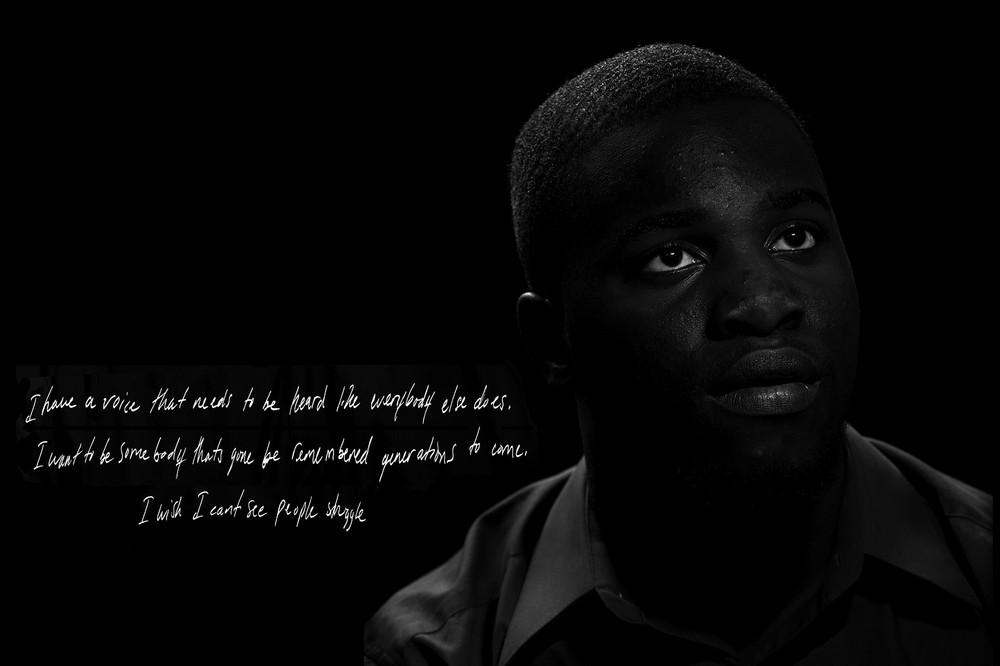

Self-portrait from Performing Statistics Project. To hear a poem written by this teen, call 804-234-3698 extension #5

What should people do if they want to become involved in this cause?

I think the quickest way to understanding criminal justice issues is to spend any amount of time with those directly impacted. Thankfully there are so many programs, services, and organizations across the US that are working directly with incarcerated individuals, their families, and returning citizens. I can’t think of a better place to start than to open your ears and hearts in your own community. Get involved in these programs and find your niche. Whether you’re an artist, lawyer, educator, counselor, teacher, police officer, activist—anything—there’s an important and needed place for you.

My role as a cultural organizer is like a dinner host. I gather a multitude of people together and help nurture the relationships from these rare and important connections in hopes of having lasting impacts on individuals, audiences, and policy decisions. But it’s largely out of my control, which is important. There’s so many people that, through the deeply collaborative process, make the work their own. It not only makes the work possible but is sustainable. Art can create the stage for people to see their own potential and place within society. We all have amazing power, how we use it is what’s important.

Mark Strandquist is a is an artist, activist, and educator who has spent years using art as a vehicle for connecting diverse communities to build empathy and support for social justice movements. Follow his work here.