This short story appears in the 2015 Fiction Issue of VICE Magazine.

I went to Knight’s brunch after all because the choral Mass in the Catholic church across the street was giving me a migraine and the woman in the window opposite ours, who my boyfriend and I call Yoga, was having sex with our building’s super. Only when I got to Knight’s apartment on West Broadway did I realize I had my days mixed up. Instead of his dining room filled with artists, it was half-filled with writers. “Can you even quote Bakhtin?” Knight said to me, which I took as an insult until Josephine told me that a downtown literary festival devoted to Bakhtin had diminished the turnout. The caterer took my omelet order. I was surprised to see that Colin had come back from Budapest. His year living in Nikolai’s dead parents’ house had done him wonders. He didn’t even look like an addict. “I’m working as an archivist for the ASPCA,” he told me, “cataloguing their pictures.” When I asked him where Nikolai was, he didn’t respond and stepped onto the terrace to shoot the water towers with his phone. Terrence and Bettina were not at all pleased about NYU’s plan for expansion. “Our street life, our gardens,” Bettina moaned. “Homeless people have a culture too, which should be respected.” Terrence laughed and said we should all be angry but not for the reasons we thought we were. I drank a Bloody Mary but didn’t like the look of Knight’s limes, desiccated even before they were sliced. I put my shoes back on while waiting for the elevator. When the doors opened, there was RJ, in a wrinkled blue Oxford and dirty white corduroys. His pinkie was bandaged, and a half-moon of blood had leaked through the gauze. “I was hoping I’d see you here,” he said, more anxiously than I expected. “Can we meet up for breakfast soon? We could go to the dog run afterward like we used to.” He texted me as I was walking to the dry cleaner, the one on First Avenue with the headshots of famous customers like Philip Glass on the walls. I wondered whether they asked for a headshot from their famous customers directly or ordered it off the internet and got them to sign it when they stopped by to pick up their clothes. “How about Friday?” RJ’s text read.

Videos by VICE

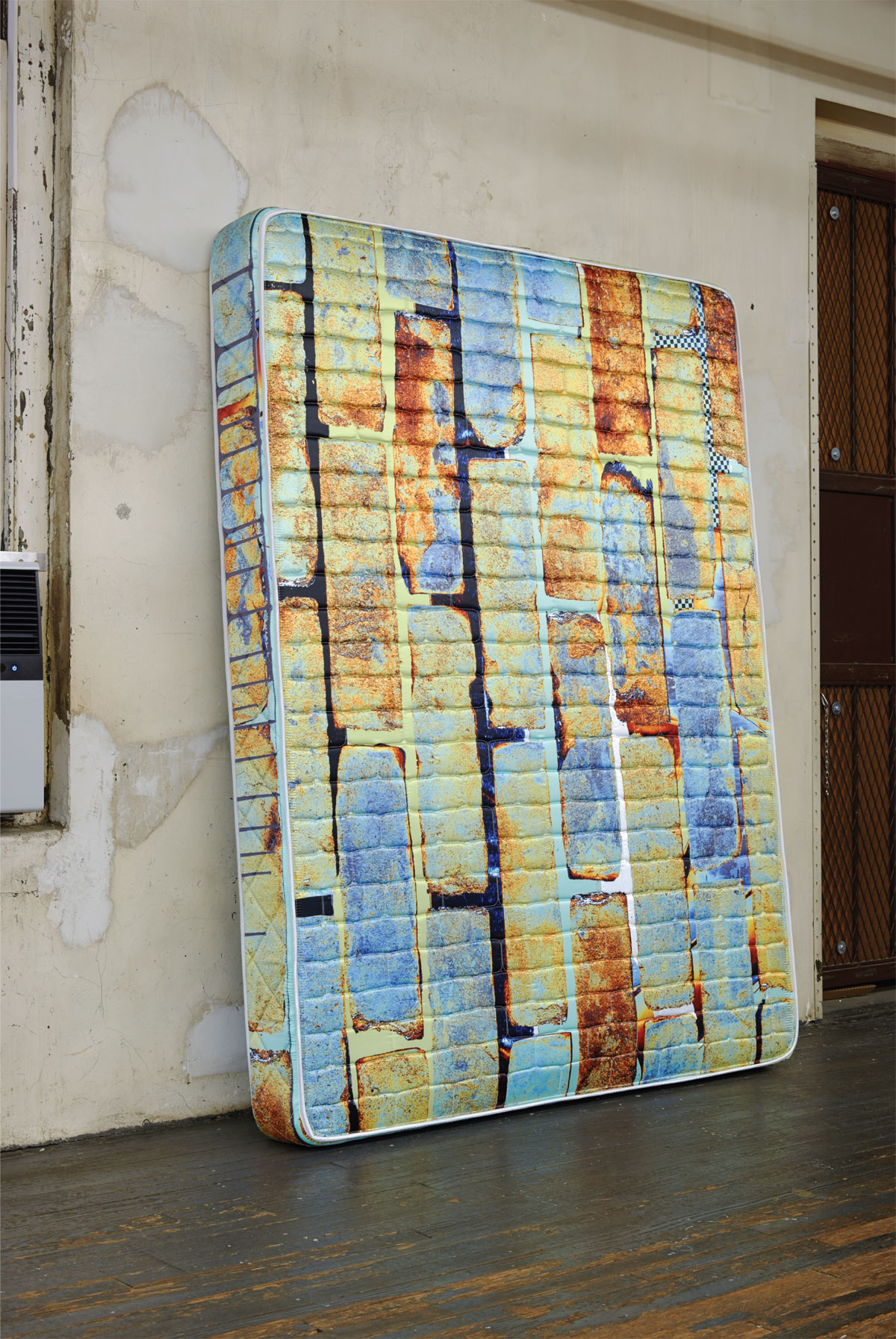

Hotpinksunrise_Mattress, 2014, mattress. 60 x 80 x 8 inches, 152.4 x 203.2 x 20.3 cm. All photos by James Campbell. Artwork By Guyton\Walker

Stefan didn’t pay his half of the rent on time. It was like a game we played, or that he played and I was forced to go along with on the defensive. I made a show of giving the rent check to our super at the first of the month, but Stefan always waited until the 15th to write me a check. The annoying part was that he had the money. I saw his bank statements. I figured he enjoyed the 15 days of feeling like he had gotten away with something. All of the utilities were in Stefan’s name because he had to establish a consistent proof of address in order to be approved for a credit card. The banks didn’t want him. Brandon said the banks were growing cautious again, that something bad was about to happen. “Hold on to everything you have,” Brandon advised me at the dinner for Con’s art opening. “I’ve taken the brownstone off the market. And I’m not doing the Berkshires this summer. Do you want to go to Lampedusa together in August?” I told him that August would be too crowded but June might not be if I could get the time off from the magazine.

Someone was pooping on the sidewalk outside our building at night. I thought of Bettina, although she lived on Sullivan. There was fecal matter in the morning on East Fourth Street, and it wasn’t dog feces. It was bloated and brown, reeked of human digestion, and was impossible to wipe off. Rats had gotten rarer, but their rarity only made an individual rat sighting more alarming. The F train was stuck between stations, and when I finally made it to the Whitney the bar was shutting down, candles placed as a barricade in front of the bottles. The bartender said he was off the clock but also wouldn’t let me pour my own glass of wine. Agnes wore vintage Schiaparelli and ankle wraps and kept grumbling about the exhibition on the third floor. There was no calming her. “And the current young people are even worse than the last young people,” she shouted. She took me and Marlo to Sant Ambroeus and paid for our vodkas. I wanted to sleep with the Italian waiter manning the front tables, his pink apron double-tied around his slender hips, but he shot me glances to indicate that my staring was making him uncomfortable. I spoke in Italian to convince him I was only interested in a language partner. When I came back from the bathroom Agnes had gone and Marlo said her medication wasn’t mixing well with the alcohol. “Poor RJ,” she said. I asked her what about RJ? She shrugged and confessed that her work wasn’t selling and her gallerist was threatening to let her go. In the cab home I texted RJ. “What’s going on with you? Are you all right?” The next morning I read his 2:14 AM reply: “Are you free for coffee on Monday? I really need to talk to you.”

Cathy had either been raped or not been raped. She didn’t know. She had gotten so wasted at the Control Room she had brought home three Norwegian guys and blacked out on her bed after kissing two of them. When she awoke the next morning there were condoms everywhere and a note on her fridge thanking her for letting them crash. She said she didn’t feel like she had been touched and only her bra was off, but what about the condoms? What about the fact that there was semen in one of them? She told me this at the Control Room in the alcove by the bar. She began to cry and I hugged her. I told her she should probably take a test. She said she would but she wasn’t sure which kind. “They were only passing through,” she said. Stefan showed up at 11:30 and told me I was embarrassing myself. He said I should never dance, not slow or fast. Talia invited us to her spring picnic in Prospect Park. “Lauren and Andre and RJ are coming,” she swore. Stefan and I said we’d go, but we didn’t like Prospect Park, and on the day of the picnic we went to the movies and to a lecture on Marxist forms of circulation at the Kitchen. There were no audience questions.

A Japanese cherry tree was blooming on 14th Street. Every time a crosstown bus drove under it, the windshield hit its lowest branch and purple buds rained down on the pedestrians.

Everyone went, “Ohhhh.” After a few hours, a park custodian arrived to saw the branch off. Often, while walking, I got the feeling that someone near me had his hand on a trigger, and at any moment there’d be a blast and I’d get caught up in it. I tried to avoid the squares: Union, Herald, Demo. RJ used to work off Demo, designing artists’ websites. I thought about stopping by his place on 12th Street, but I wasn’t sure he lived there anymore, and the buzzers listed residents who had long moved away. When my cell phone died, I realized the city had stopped investing in public clocks. Who knew for how long that had been going on?

Drippy Brick_blue_mattress, 2014, mattress, 60 x 80 x 8 inches, 152.4 x 20.3 x 20.3 cm

My psychologist wouldn’t let me talk about Stefan. Neither would Monica when I ran into her at the gym. “Don’t get me involved in your guys’ problems,” she said. “I don’t want to know.” My parents were divorcing and that was fine for both of them to hear about, but Stefan was off limits. Over Ethiopian food, Stefan asked whether I wanted to go to Lampedusa in August. I asked if he had been speaking to Brandon. He said he hadn’t and that if Brandon was planning on Lampedusa in August we should go to Pantelleria. “I can’t trust you when Brandon’s around,” he said. “You start acting like someone else. It’s weird.” I asked him if he had noticed human feces on the sidewalk lately. He said he hadn’t but would keep an eye out.

We learned in early summer that Nikolai had died in Budapest. No one had been able to get in touch with Colin to find out the exact cause of death or even locate an obituary on the internet. We arranged a memorial service at Rebus Gallery, even planning to hang some of Nikolai’s old paintings, but since no one knew what had killed him or when, the whole event seemed presumptuous and maybe distasteful. The super and Yoga continued their affair with such indiscretion she didn’t bother to close the window when they had loud sex. Stefan and I hadn’t put blinds up on our windows, so we avoided the bedroom in the afternoons. “It sounds rough,” Stefan said. We got hooked on an 80s mystery show on Netflix—one that involved a real detective and a fake detective who becomes her real partner in solving crimes—and we missed three birthday parties and half a day of work while binge-watching all five seasons. Stefan noted that most of the detectives’ troubles would have been fixed with the advent of cell phones. “Especially the love part.” Our air conditioner needed to be replaced. At night, after Stefan fell asleep, I repositioned the fans so they’d blow on my side of the bed. The heat put a run on Nyquil at the pharmacy.

The weekend that Stefan went to Fire Island with his friend Oliver I bought used furniture. I purchased a walnut sideboard and a Persian rug and two director’s chairs with only minor tears in the upholstery. I thought Stefan might be fucking Oliver on Fire Island, or might find someone else there to fuck, and his invitation for me to join them seemed halfhearted or purposely inconvenient because I had to interview a film director for the magazine. The film director only wanted to discuss his latest project while I kept asking him about his early films, which was my only interest in interviewing him in the first place. He wore sunglasses throughout the interview and kept moving the recorder away from his elbow. “I’m not interested in the past,” he said uneasily. “I’ve made a career out of not being nostalgic. Please only ask me about tomorrow’s premiere.” I asked him how he had conceived his iconic 1979 film without the use of a script, and he told me I was out to destroy him. When Stefan didn’t answer his phone, I called RJ and left a message. “Are you free this weekend? Do you want to have dinner?” By the time RJ phoned back two hours later I had plans to see a concert with Gilles, and I let the call go to voicemail. Gilles told me that Nikolai had taken his life. When I asked how, he snapped at me. “Why is that important?” I told him I thought the method might indicate how serious he had been. “It was serious enough that it worked,” he said. We left after the opening act and lost each other at Scully Zero Bar. When I put the sideboard on the curb, Yoga asked if she could take it. As I helped her carry it back upstairs, she told me a friend had stopped by my apartment while I was out. “He knocked for ten minutes,” she said. “He didn’t look too good.” When she described curly blond hair and red glasses, I asked whether his name was RJ. “Could have been,” she said. “That sounds right.”

Every night on my calendar was committed. The accretion had happened so slowly and with such advance planning I hadn’t noticed until I looked at my schedule for the week. Dinner with Lewis and Matthew at EN. A performance of Bartók with exploding fire extinguishers at the French consulate. A sneak preview of the architecture biennial. Why is this happening? I thought. For my job at the magazine, I stopped by a photo shoot for a young actress who was about to star in a dystopian blockbuster. “I knew since I was little that I wanted to be an actress,” she told me. “I was always dressing up, making up stories, pretending. I was always hungry for people to watch me.” I wrote that down. I applied for two autumn writing residencies and for a freelance newspaper job sculpting prospective obituaries on prominent cultural figures who might die unexpectedly any day. My mother called to tell me the divorce papers had been signed. “The needle’s been unthreaded” was how she put it.

We missed the eclipse. Apparently the moon had been red, and we missed it. Stefan was also missing vital papers for his green-card application. “Not here, not at work. Are you sure you didn’t throw them out? You never look at things before you toss them.” We attended Fetneh’s Fourth of July barbecue on her rooftop, which ended in a fight on the way home in a cab about my drinking. I wrote a comedic piece for a friend’s blog on the perils of indoor gardening. My friend said it was a popular article even though only one anonymous comment had been left about it. “Nice job. You have great timing.” I thought the comment might be from RJ. When I tried to call him, his phone was disconnected. He didn’t respond to my messages on Facebook, and his page hadn’t been updated in months. I saw a photo of us from two summers ago, on the Hudson River piers, each of us hand-forcing the other’s mouth into a smile. RJ and I touched each other a lot then. I remembered how extra-naked he looked when he was naked, maybe because his skin was so white or because he kept his glasses on.

At a party at Brandon’s brownstone I tried a new drug that turned out to be an old drug with a new name. I might not have taken it if I had known, but it didn’t stop me from waving my hand through the sunlight in the garden. Every tree seemed to have been designed with such precision. The sun was hot, but the concrete felt soft and cool on my feet, and I loved how everyone stood around taking pleasure in the tiniest insects. Should we bother with Rome before Lampedusa? I had separate conversations about this with Brandon and Stefan, weighing pros and cons. I was pro. Rena invited me to her parents’ house in South Hampton, and I took the Jitney, marooned in eastbound traffic for five hours. Her swimming pool was the infinity kind, and she took a break from reading the Times art reviews in cartoon voices to tell me that I looked handsome in my trunks. “You look skinnier and more chiseled,” she said. “Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it.” I asked her if she had seen RJ lately. “No, but I heard he was struggling.” When I told her that Nikolai had killed himself, she stuck her finger in her drink and licked it. “Untrue,” she said. “He’s in Tel Aviv working for the resistance.” We went to a party at a beach house that used to belong to Billy Joel and now belonged to the ex-wife of a Jordanian businessman. There were white pianos in every room, but the keys were sealed in plastic. “David Bowie used to send me roses,” the owner of the house told us. “By the truckload. It hurt to gather them up.”

Pink_Grapefruit_mattress, 2014, mattress, 60 x 80 x 8 inches, 152.4 x 20.3 x 20.3 cm

The super’s wife moved out. That was not confirmed, but I hadn’t seen her in weeks. Neither had Stefan. But Yoga hung a batik over her window, and I found the sideboard I had given her blocking my front door one morning. I carried it down to the curb. The super was hosing feces off the sidewalk, and he didn’t stop the spray when I passed, letting the water rinse my shoes. The magazine was threatening to fire me if I didn’t make a point of showing up on time. “Your nights are your own, but we need you at your desk during the days. We’ve been keeping records. We also found an obituary on your computer for Philip Glass.” I was hoping to keep the job long enough to use my two weeks’ paid vacation on Lampedusa. Brandon wasn’t going. He decided to do the Berkshires after all, but Stefan was on the razor’s edge of buying our tickets. “Let’s go,” I said. “I hate it here in summer.” I decided that if we didn’t go to Lampedusa we should take a break. I kept looking for signs of his cheating on me with Oliver. I even read their text exchanges on Stefan’s phone: “what u up to?” “nothing, bored,” “me 2,” “drinks?” “this week,” “saw RJ, sad to say goodbye.”

I couldn’t ask Stefan outright why Oliver had said goodbye to RJ because Stefan would have known I was snooping. I asked him casually about RJ while he was practicing the cello in the living room. “Poor guy,” Stefan said. His strings needed tuning. “Sucks about losing his apartment along with everything else. Some people just have to go.”

People weren’t eating much. I noticed this trend at dinners. People either had already eaten or were forgoing dinner altogether. And no restaurant served halibut anymore. I finally asked a waiter about it at the dinner for Leslie’s linoleum sculptures in Central Park. “Halibut has gotten very expensive,” the waiter told me. “It’s been overfished. Red snapper’s still plentiful. Try that.” I shut myself up for a week at my desk at the magazine. Advertising was declining, so they needed content to fill the empty pages. I wasn’t chosen for either residency. “You made the penultimate list, but we went in another direction.” Olympia’s fundraiser cocktail to save the nonprofit art space Luminary was a washout. The only guests who attended had been comped. She blamed it on summer atrophy. There were rumors of a serial killer murdering the homeless around the East Village with poisoned free food, and again I thought of Bettina, but it was only a rumor, and the newspapers hadn’t picked up the story. Still, no one felt safe handing out sandwiches. “What if you could poison spare change?” Ryan said. “We’d all be in trouble.”

When I looked up, it was August. The double-decker tourist buses were jammed. I texted Stefan, “What happened to our vacation? I thought we were going to Lampedusa.” He wrote back, “We have to talk.”

Oliver helped Stefan move out. They carried his furniture down the five flights, even the houseplants we had bought together. To be fair, caring for them had always been Stefan’s hobby. I was panicked, left in the lurch. I told Stefan he should have to pay his share of this and next month’s rent, at least until I could find a roommate. “I already paid for August,” he said, rolling up the Persian rug. “I gave a check to the super two weeks ago. Guess what I wrote on the note line?” I said I didn’t care. “I wrote, ‘Tell #5F to put a curtain on her window.’”

I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t sleep for several nights, even with the fans pointed on me. I worried about homeless people being murdered and NYU’s expansion plans. Were they related? I worried about the super’s wife. I worried about Nikolai in Israel. One morning, I got up early and walked around the neighborhood, in the quiet window between bar closings and the work rush. The rising sun lit the puddles orange and green. I threaded through the park and saw a young man with blond hair and red glasses leaning against the gate of the dog run. It was RJ. My first instinct was to flee. He waved to me. His pinkie fingernail was missing, a lemon peel of a callous in its place. I asked what had happened to him, where he had been. “I moved away,” he said, smiling. “I tried to meet up with you to say goodbye.” There were only a few dogs in the run at 7 AM and just two that had the energy to chase a tennis ball. Their owners drank coffee and read newspapers on the benches, some still in their pajamas. “I went back to Oklahoma,” RJ said. “But after two weeks at my dad’s house I was so bored and broke I decided to come back. So here I am, starting over.” A Labrador was trying to remove its muzzle by rubbing its snout across the ground. “Root Beer, don’t,” its owner shouted. I told RJ that Stefan had left me. “Maybe that’s not so bad. He was just cover for you anyway.” I didn’t know what he meant and didn’t feel like knowing.

RJ walked me back to Fourth Street. It seemed like he had time to fill. We stopped on the corner. “Do you know what really hurts—” he began, but he was distracted by something behind me, and when I turned I saw him. An old man, 60 or 70, with a white waterfall beard, his green pants bundled around his feet, squatting like he was sitting on an invisible chair. His legs were hairless and scabbed. He was pooping on the sidewalk, using one hand as toilet paper and the other to steady himself against the building’s brick. His eyes bulged when he looked up at us, a rinse of colorless fear, and he staggered to lift his pants. He yelled, “Gotta go somewhere, no place to go.”