Rows of F-4s lay idle at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona. All photos by the author

The United States currently boasts 5,448 active aircraft, giving it the world’s largest air force by far. Russia comes in second with what is generally estimated to be a bit less than half that number, but that’s still fewer planes than America has stashed in its maintenance and regeneration facility. I visited what is affectionately known as “the Boneyard” at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, to see what amounts to the world’s second-largest air force.

“We have around 4,000 aircraft here,” Public Affairs Officer Teresa Pittman told me, “though that number changes every day.”

Videos by VICE

The Boneyard emerged after World War II as the stash spot for a massive surplus of planes. Some of them have been baking in the Arizona desert for over half a century. The perfect climate, as well as the dedicated work of the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group, keeps most of them in – or somewhere close to – flying condition. Now, in the wake of military withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan, the Boneyard is again crowded with aircraft waiting to be scrapped, mothballed, used for parts, turned into museum pieces, or sold to foreign allies.

I stood with the cheerful Pittman on the tarmac, holding onto my cap, as the most recent arrival touched down. Like 98 percent of the aircraft there, the helicopter came in under its own power. It was an HH-60H Seahawk, but the men just called it a “Hotel.”

This particular Seahawk was special. “It has more combat hours than any aircraft in the Navy,” the pilot, a Navy lieutenant commander, told me. (Pittman requested that I obscure the pilot’s name for reasons of personal security.) The pilot and crew bringing it in were the same crew that had flown the Seahawk in battle. They were from the Red Wolves Squadron, one of two in the Navy dedicated to supporting the Special Forces. I asked the commander about some of the missions he recalled involving this craft.

“Typically, we’d have between two and eight aircraft, rotor wing. We’d have AC-130 gunships supporting us, Apaches. We’d carry assaulters in. Sometimes, we’d land a little distance away from the target, and they would sneak in. Sometimes, we’d land right on top of the target, and they’d go in – snatch and grab guys. Sometimes, you’d have targets that would start running away. We’d track them down, and talk the ground troops onto them.”

When asked about the mission that had meant the most to him, the pilot recounted an operation he had led on September 11, 2009. “We got a high-value al Qaeda operative who had been known as a bad guy,” he replied. “He’d done some things to injure and kill US and coalition troops. It was fitting that it was the anniversary of the World Trade Center attack.”

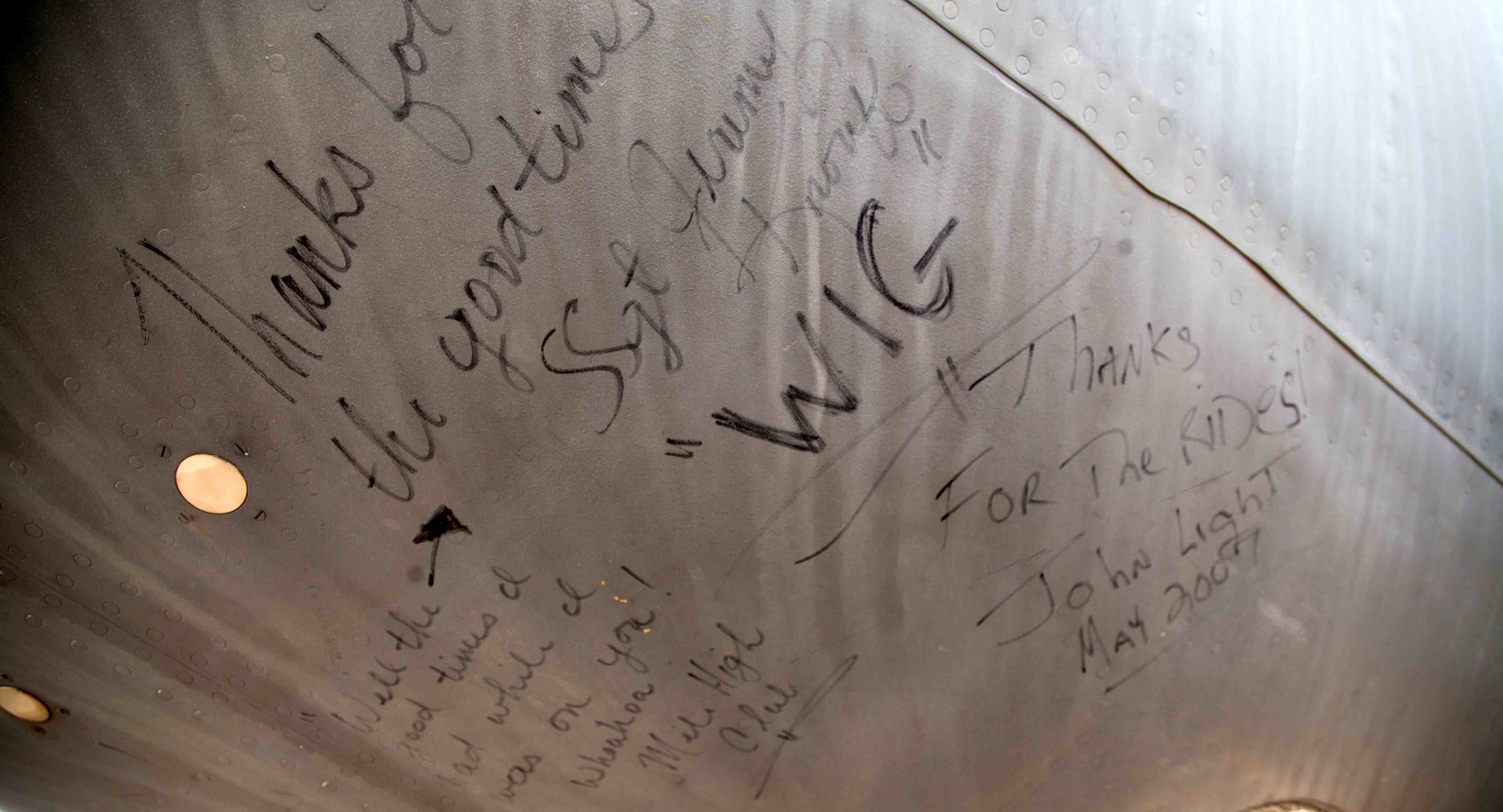

Like many of the aircraft here, the Seahawk had been written on with markers by the crew to commemorate its final flight. “Unfortunately,” the pilot added, “due to sequestration, both squadrons are getting cut. That’s the reason we’re flying in this aircraft, shutting it down. It’s a sad day. I understand they’re replacing them with newer aircraft, cheaper to operate and maintain. Progress, I guess. It all has to happen.”

The almost anthropomorphic bond the crews have with their aircraft was evident everywhere. The messages written on the various fuselages said things like: “Thanks for the good times!” One simply bore the phrase “Last flight” with a name and a date. Occasionally there was something cheekier, like a reference to the “Mile High Club.”

Pittman spoke of the calls she regularly receives from former crew members who want to visit their old birds. “I see more attachment by the crew chief that gets her ready to fly,” she noted. “I get a lot more calls from crew chiefs who want to see their old planes. Sometimes we can help them, and sometimes we can’t.”

We left the tarmac to wander among the seemingly endless rows of aircraft in tidy lines. Everywhere we looked, there was a story. In the nose art, there was a definite drift towards political correctness as time advanced – there are no more scantily clad girlfriends and buxom Dolly Partons these days. Grinning skulls, though, are still Kosher. There were the big “Let’s Roll!” eagle and American flag decals on some of the transports from the feverish weeks after 9/11. There was President Eisenhower’s old Army One helicopter rusting away in a corner. There were fields of cut up and demilled B-52 bombers. At one time, they had been America’s first line of defense against the Soviet Union; now they are casualties of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). Their dismemberment is accentuated so Russian satellites can confirm their destruction.

Several F-15s sported kill markings from earlier wars. Beneath one of the cockpits, a small Iraqi flag was painted, overlaid with the words “MIG-23 KILL JAN 28 1991.” The fighter had been flown by Captain Don “Muddy” Watrous in the early days of the first Gulf War. He had been separated from the other aircraft in his squadron when he engaged an Iraqi MiG near the Iranian border. The bandit apparently dodged three of his missiles before the fourth hit home.

Like “Muddy,” just about all the pilot names stenciled beneath the cockpits were some kind of nom de guerre, like “Wig,” “Cheese,” and “Snap.”

“The names are a rite of passage,” one of the pilots explained, adding that the best and most beloved ones are deprecating in nature.

We moved on past a couple of crated F-16s bound for Indonesia to a hangar where similar fighters were being turned into unmanned drones. The radio played country music as the mechanics moved gracefully beneath the glossy fuselages.

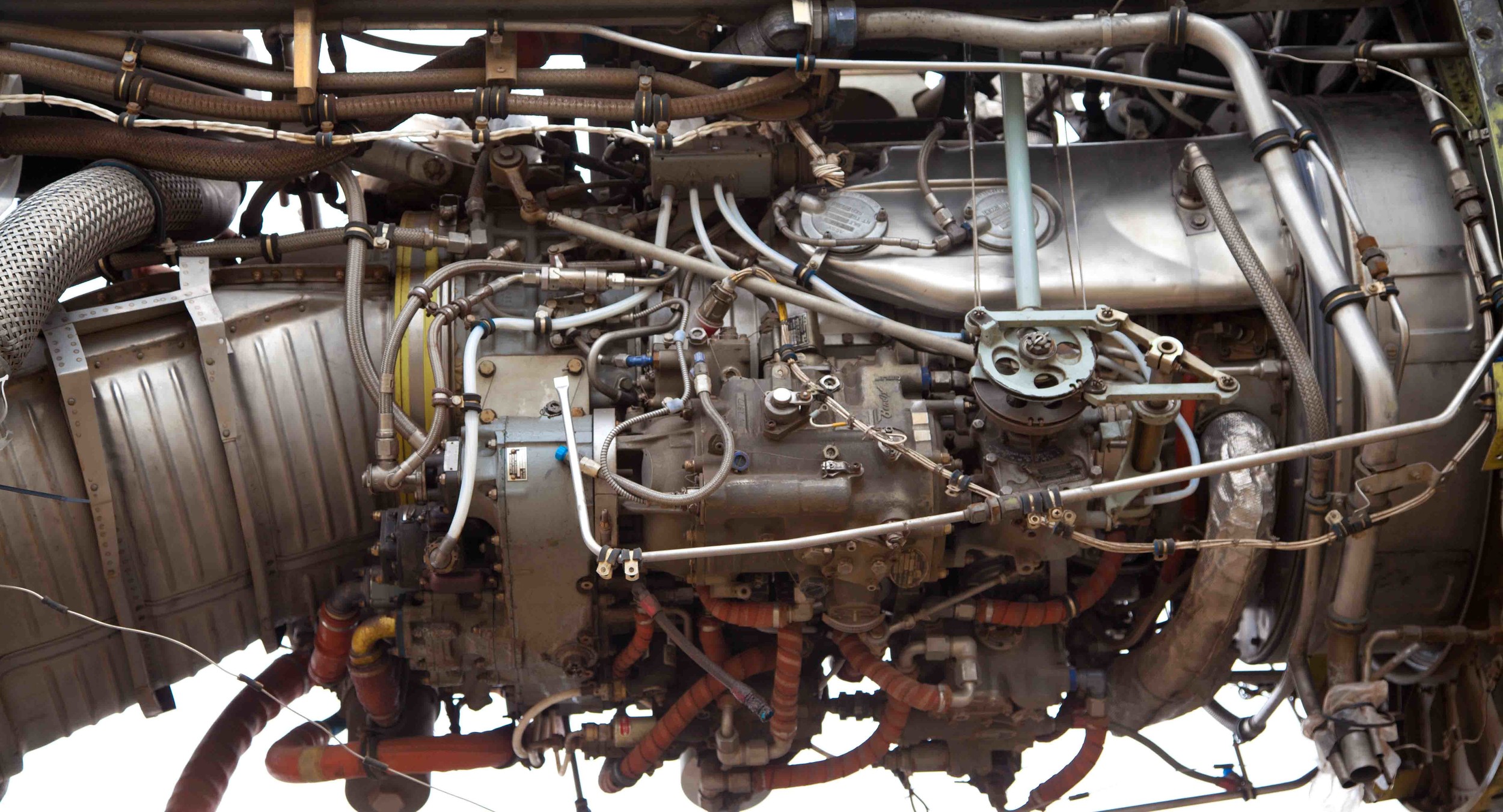

Next, we visited a pair of techs working on an A-10 warthog. One of the jovial mechanics recalled having seen some of these birds in action knocking out tanks during Operation Iraqi Freedom. The A-10s are known for their extreme robustness, and yet, with their innards exposed, they seemed rather delicate. The tech pointed out a long, thin wire winding through a mass of machinery. It looked insignificant, but he explained it was a kind of Achilles heel. If that little wire were to be severed, the plane would be incapacitated.

“What’s going to happen to this A-10?” I asked.

“It’s headed for the shredder,” Pittman replied. “It could become a car or an aluminum can.”

Our last stop was an open-air hangar where fighters were being repaired and outfitted with onboard oxygen generators. Up above, a family of owls had built a nest. The technicians had constructed a box around it to keep the chicks from falling out. We spotted the male perched high above on a steel beam. He was a perfect mascot for the Boneyard – another fine example of historical flight technology.

Follow Roc’s project collecting dreams from around the globe at World Dream Atlas.

An example of post–9-11 Let’s Roll! nose art

An A-10 with tiger nose art

An F-4 with C130 in the midground and C-5s further back

Atop a C-5 transport plane

A B-52 bomber that was dismantled as part of the START Treaty

The cockpit of a C-5

A set of C-5 Galaxies

Some C-5 nose art

Civilian airliners

A civilian airliner

A C-130 engine

Some F-4s in storage

Damage caused by birds

An F-16 awaiting shipment to the Indonesian Air Force

A detail of a OH-58D Kiowa helicopter

A parting message left by crew

A Harrier jet

A lieutenant commander standing in front of his Seahawk

A C-5 transport plane being prepared for storage

An A-10 awaiting the installation of an onboard oxygen generator

Nose art on a C-5

Some C-5 transport aircraft

C-130s

A C-130 in reclaimation

Some CH-46 Sea Knights

A close-up of Eisenhower’s Army One Helicopter

An F-16’s gun

Eisenhower’s Army One helicopter and a Tornado stored for the German government

An F-15

An F-16 being modified into a drone

F-16 being disassembled for overseas sales

F-16s in storage