At the beginning of the 20th century, science fiction films portraying what the future might be like probably catered to the audience’s expectations of what Heaven would be like. The Airship/100 Years Hence (1908, director: J. Stuart Blackton) aimed as high as people dared dream at the time: the “air” (“space” didn’t exist yet). The film predicted that happy people in 2008 would ride airborne bicycles with pedal-powered propellers in place of wheels, and police would fight “air crime” with helium balloons attached to electric fans (mostly making sure women’s ankles weren’t exposed—fashion hadn’t budged in 100 years).

Sky Ship

Sky Ship (1917, director: Holger-Madsen) pushed the fantasy farther. Brainy Danes are able to fly to Mars in a propeller-driven “skyship,” finding the planet’s oxygen-rich atmosphere populated with Nordic, ankh-wearing vegetarians who hate war, live in Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, and do fertility dances. Again, smiles all around.

Leave it to German filmmakers to reinvent future fantasy as future cynicism for a moral lesson. In the 2026 of Metropolis (1927, director: Fritz Lang), conflict in wonderland reflects mankind’s eternal struggle. Produced during the height of the Weimar Republic, this elaborate film depicts a corporate state where smart and pretty people live in glorious towers, ugly workers toll down below, and industrial revolution tensions loom deeper. Revolutions begin, both lead by women (one flesh, the other wires). Cities feature television intercoms, automatic doors, monorails, air cars, kooky fashions, robot girls, and enough art deco to fill your gay grandfather’s mausoleum.

By the 1930’s, future “lessons” became realistic and expansive. Things to Come (1936, director: William Cameron Menzies) begins after an unexplained world war. The remaining population (100-percent Caucasian) wanders around demolished cities. By 1970, brainy types in crazy-looking outfits mine remaining resources (in Iraq of all places—no joke) and the industrial revolution is back on. By 2036, sparkling new underground cities look like luxury hotels, with glass tube elevators and holograph-TV. Happy citizens watch their almighty leader’s giant face projected overhead, giving them the latest news, which is: Everyone get psyched because our first trip to the moon is about to happen! The rocket is right over there, see? Wait, what’s happening down there? Unrest? Some of you think technology has gone too far? A riot? Hey… don’t topple over that rocket! You’re starting another war! Awwwww…shit.

The prosperity of the space-racy 1950’s had many audiences feeling the future had kind of already arrived. Imagining “tomorrow” meant imagining slight improvements to technology that had already infiltrated every suburb. Films about technology running horribly amok became adequate therapy for audiences unable to express fear of progress, which was unpatriotic.

In Gog (1954, directed by Herbert L. Strock), even if the robotic inventions amaze, the scientists are all pipe-smoking, condescending creeps with pointy goatees, foreign accents, and an open disdain for American etiquette. The film’s tag line reads: “Built to serve man… it became a Frankenstein of steel!” Joe America beats the damn thing down with a baseball bat.

Even poor Dr. Morbius, the brave, smart, hard-working (Semitic-looking) American philologist in Forbidden Planet (1956, directed by Fred M. Wilcox) can’t catch a break in 2200. The all-American space army crew wins as Morbius (and his remarkable discovery of a planet’s hidden, 20-square-mile-wide, self-sustaining, inward-looking, super-computer) fails.

By the 1960s and early 70s, the future was something that people could look forward to again, if only to say “I told you so.” Revenge fantasies bloomed hard via the hippie generation, who couldn’t wait for the grid to come down to make room for their commune.

In Idaho Transfer (1973, directed by a crying indian, no… Peter Fonda), teens travel 56 years into the future to save mankind from becoming a wasteland. They eventually discover people who’ve started all over again from the ground up: all filthy, mute retards who eat mud and are near death. One character goes even farther ahead in time and meets a bunch of jerks in bubble cars who chuck her in their tank to use for fuel.

In Zero Population Growth (1971, directed by Michael Campus) the mid-70s end up a smog-choked sauna thanks to mom and dad having 6,000,000,000 babies. The government uses subliminal advertising to discourage childbearing, providing couples with robot babies to play with. One couple goes behind Big Brother’s back to make the real deal, and instead of maternity leave gets death row.

In Privilege (1967, directed by Peter Watkins), Paul Jones portrays a pop star used by the government to sing secretly-penned product-pushing songs. He eventually pushes God, turning “Onward Christian Soldiers” into a smash hit complete with Nazi-salute dance moves (the film’s blasphemous, pyrotechnic-crazy concerts accurately predict what Alice Cooper and KISS would be doing onstage only scant years later).

Filmmakers of the era also discovered that the crazy-looking modern architecture that began sprouting up everywhere in the 70s could be used instead of expensive sets. Just plop weirdly dressed people and a few hover cars in front of I.M. Pei’s fabulous new city hall design—it’s the future!

In Futureworld (1976, directed by Richard T. Heffron), the most expensive amusement park of 1979 (actually the George Bush Airport and Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas) allows any fantasy imaginable, using human-like androids as actors, props, and whores. Only the rich and powerful can afford the resort. Leave it to two resourceful Woodward and Bernstein-type reporters to uncover the park is secretly replacing the world’s elite with identical replicants!

The hedonistic late-70s mindset greatly affected the sci-fi movie genre: Even if they were doomed and corrupt, the future became glitzier and more orgy-bound.

In the 2274 of Logan’s Run (1976, directed by Michael Anderson), postwar citizens live in domed cities (actually, the shopping malls of Dallas, Texas) where Love Shops, Relive Centers, New You Shops, Hallucimills, and free subways indulge every desire. A supercomputer (an omnipresent, sexy female voice) keeps populations in check by exterminating everyone at the age of 30 (masking the carnage in a fake religion called “Carousel”). A policeman assigned to exterminate rebels is seduced into becoming a rebel himself. He and his barely-dressed female seductress break into the outside world, decide “everything hurts,” shrug their shoulders at overgrown Washington DC, and freak out upon meeting an actual old man. Their knowledge overloads the computer and the city destroys itself, setting all citizens free (probably to starve to death).

By early 1980, visions of a filthy, grimy, high-tech future filled with jaded, dysfunctional “get real” shmoes in films like Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982, both directed by Ridley Scott) spawned an immovable trend in the genre, while simultaneously somehow giving birth to Trent Reznor’s entire brain.

But by the mid-80s, future-outlook was dominated by ironic resignation. Audiences realized the world wasn’t going to blow up, deplete itself, or overpopulate (anytime soon). We weren’t going to get flying cars or time travel, but advancing technology was certainly going to jam everything else we could dream of down our throats in wave after wave of consumable products. Terry Gilliam’s perceptive

Brazil

(1985) predicts this (although Woody Allen’s 1973 film Sleeper gets a nod).

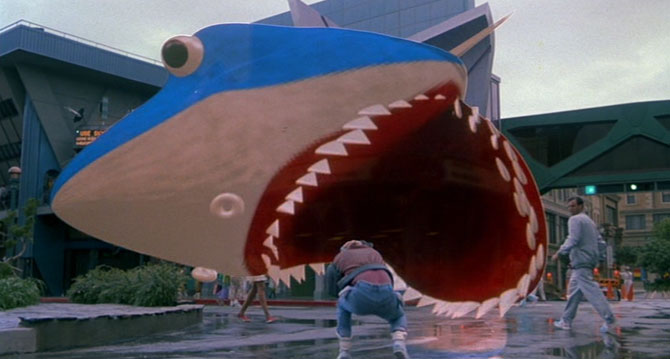

The 2015 of Back to the Future II (1985, directed by Robert Zemeckis) has flying skateboards (and cars, and schools), self-fastening Nike sneakers, push-button Pizza Hut-brand hydrating ovens, movie sequel hell (Jaws XIX), automated 7-11s, cell phones/blinking virtual-reality goggles, simultaneous multiple TV walls (instead of a channel-changer), floating upside-down back-pain devices, self-adjusting metallic clothing, long brimmed baseball caps, and the perpetual myth of new-wave hairstyles for all tomorrow’s “bad asses.” All these products immerse the citizens of tomorrow in a stressful but product-placement-friendly world, where product placement welcomes product placement with product placement that places products in just the right product placement.

Back to the Future II

The little-noticed TV show Max Headroom (1987, created by Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton) predicted a 2005 where news and entertainment television networks control everything, with thousands of reality shows and 24-hour webcam networks, and viewing habits monitored by the second. One mogul invents the “Blipvert,” a high-intensity subliminal television commercial jamming a full ad into a microsecond (that can overload your neural network and explode you). An underground of “Blanks” upload video clips onto something called an “all-accessible worldwide computer network” for citizens to download and view. Max Headroom, the uploaded brain of a murdered reporter who tried to expose Blipverts, appears on screens everywhere to crack one-liners about current events. Ironically, Max Headroom eventually became better known for his New Coke commercials than for the TV show in which he made fun of commercials.

Sadly, the avalanche of cheap commercialism that the 80s version of the future predicted and laughed about came true in the videos and DVDs of the 90s and 2000s: rehashed, already copied movies that are just commercials for DVD sales. The Matrix (1999, directed by Andy and Larry Wachowski) is arguably philosophical, but inarguably a huge fucking deal to many, delivering non-Christian concepts about perception to people who hate books. But its 2199 is unimagined from the cheapest stock template. Still, it spawned a zillion pallid imitations (the spindly track our culture is still putt-putting along today).

And so, upon looking back over 100 years of “cinemagination,” which film predicted the future most accurately? Brazil would probably be most people’s choice, though its apocalyptically funny future is still a masochistic fantasy (I mean, look around you). Max Headroom could be the little known TV show that ends up winning the prize for its prediction of news/entertainment/internet domination, but the rest of it is too twee. So the winner, based on crassness alone, is—“Roads? Where we’re going we don’t need roads”—Back to the Future II! Even though it got all the best things about the future wrong, more importantly it got all of the worst things about the future totally right.