Some producers are savants who put in as much, if not more, to the creative processs as the artists they’re working with. People aren’t paying Rick Rubin millions of dollars for him to make the hi-hat a bit louder. Others are basically glorified engineers, they let the band tell them what they want and then just fiddle around when they’re not looking

In either model, the work of the producer is often painful and laborious. They work with bands to trawl through their eight hour drum solos, excessive guitar wanderings, meaningless synthesiser chord progressions and vocal warbles, until they can construct something that sounds remotely like “a song”.

Videos by VICE

But what if your tastes were so abstract, you didn’t even need a producer? Well, if you thought your job was only at risk to the AI and robots if you worked in manufacturing, then start shitting yourself now, because it seems like even the most creative roles are usually, at their essence, just maths, really.

When the musician John Supko and media artist Bill Seaman – known together as Straits – were writing their album, they amounted a 110 hour database of field recordings, acoustic and electronic instruments, analog and digital noise, cassette recordings of their older material, loads of piano and even some soundtracks from 60s and 70s documentaries. But instead of working with a producer to find the album within all this, they decided to create a software, called bearings_traits, to diligently fish through the entire database using complex algorithms, and put together various juxtaposing bits until it starts resulting in melodies and grooves. Then Supko and Seaman jump in at the last to mould the cybernetic producer’s works into single, manageable songs.

The result is a 26 track album called s_traits, a mind-whisking collage of spectral electronic music, that verges on contemporary classical at times, and is made all the creepier when you consider it’s the product by three minds: two human and one very, very artificial. The classical critics at the New York Times regarded it as one of the best releases of 2014.

I got in touch with Straits’ John Supko to talk about having an artificial intelligence produce your album, whether it knows best, and if it really has a practical future away from experimental music?

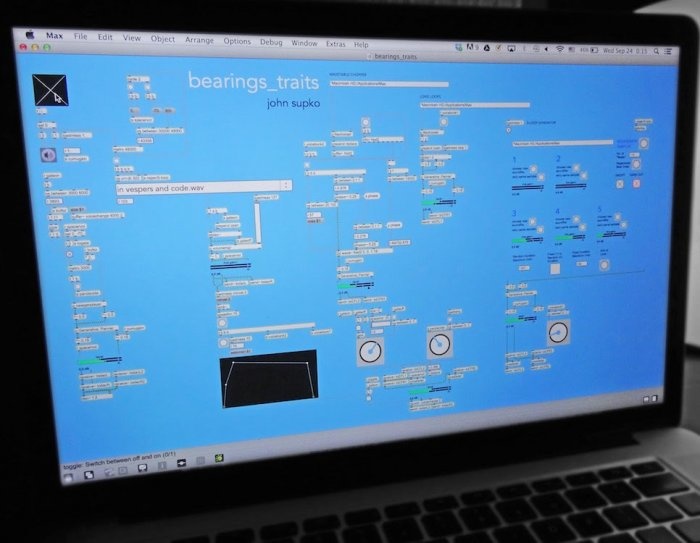

bearings_traits working away on a song here.

Hi John! So when did you decide that a computer would be your producer?

Well, since we had this huge database of musical material, we thought that there were bound to be lots of musical possibilities that we would never discover on our own. It’s a pretty involved process to go through samples, select the ones to work with then start slicing, dicing and recombining. Obviously, this is how humans create music and there’s nothing wrong with it. But we just wanted to find a way to generate lots of possibilities very, very quickly.

How efficient. Does the computer have a tendancy to take things down a certain route? I feel like artificial intelligence would enjoy gabber.

No, the computer doesn’t have any taste of its own, which means it didn’t make any unhelpful assumptions about what might or might not be good. It simply spat out what we asked for. Then we were free to keep or reject the results.

So how does the software actually work?

Okay, our 110 hours of audio database was loaded into the software system, which we call bearings_traits. The system then goes through all the audio and selects bits from samples, from which to make rhythmic grooves and melodies. The system has the ability to crossfade and pan the audio in unpredictable ways, remixing the material generatively. It can also sample itself: it records the material it generates and then integrates it back into the mix, often altering it first by changing the speed or using bits at irregular or regular time intervals, creating a new rhythmic element.

How did you end up with those 110 hours of sounds, music and loops in the first place?

Bill and I were discussing collaborating on a project around 2011. As a way to begin, I sent him the discarded electronic track of a percussion track I wrote called “Straits”. This track lasted about 15 minutes and had lots of interesting material that I thought we could use for our collaboration. So Bill cut it up into tiny samples, some lasting barely a second. That was the start of what would become the database. Then we just kept adding to it, essentially hoarding audio until it got way too big.

Let’s talk scary stuff: how do you see computers taking over music?

I think that computers have the potential for suggesting creative possibilities that humans might not see or consider on their own. This has to do with certain assumptions we make when we’re working. We assume X or Y will not work or be worth pursuing because of A or B reason, so we move in a different direction. But what if we could actually try out X or Y (and hundreds of other possibilities) and then make a decision? That’s how Bill and I worked on s_traits, allowing the computer to take us in directions that we would have never tried ourselves. So while I’m not sure that “sophistication” is increasing here, I can say with reasonable certainty that computers will have an increasingly intimate role in the creation of music in the future.

What did the computer teach you about the process of creation?

Working with the computer’s suggestions is quite addictive. It means that I don’t have to rely on my body to come up with ideas: I don’t have to improvise at the piano or write things down on paper. Those processes always involve memory in some way, and when I improvise ideas for a piece at the piano, I’m pretty much remixing things I’ve played (muscle memory) or heard (auditory memory) before. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, it’s 100% human and how most music has been made for centuries. But there’s no reason that human creativity needs to be restricted by human physiology. The computer allows me to generate a lot of material and then decide — almost as a listener decides on first hearing — whether I like it or not. If I like the material, I work with it, developing it into a composition. If I don’t like it, I throw it out and ask for more. I think this is an important change in my working methods because it allows me to compose in a way similar to how a listener listens.

What was the reception like to the album?

To my astonishment, people seemed to really like it. I’m surprised because some of it is very strange music. Sometimes, I get the sense that the music of s_traits was written in a parallel universe, perhaps because it was all constructed out of the same huge database, but I didn’t know if that universe was going to be hospitable to other listeners. Luckily, it seems to be.

Could it ever replace real producers?

I hope not. I’ve thought of the computer as a collaborator, but not a replacement. Besides, the system is not sophisticated enough now to come close to replacing a human musician. There are plenty of functionalities I’d like to build into the system. My motivation would not be to make the system more human in its behaviors but rather to enhance its “computerness,” since I believe it’s that quality that adds something special to the music — the strange logic, the crazy mechanical rigor, the emotional detachment.

Do you reckon it deserves a royalty?

Ha! No, because I made the program. So maybe I deserve double royalties!

Thanks John!

You can follow Dan Wilkinson on Twitter.